| In the past when architects and designers mentioned concrete, people rarely got excited. It usually meant a dull, grey, visually unappealing appearance. Today though, thanks to new technological advances, concrete can be cast in a variety of finishes and colours offering architects and the construction industry a material that is both eminently practical and aesthetically pleasing. Coloured Concretes Since the introduction of modern pigmented concrete products in the early 1950’s, the popularity of coloured concrete has increased rapidly over the past few years. In many towns and villages it is now common for planning authorities to specify the use of coloured building materials to help retain its traditional character. But technology has moved beyond even this, enabling artistic images to be incorporated in the very fabric of a building. Coloured concretes have been used to dramatic effect in new structural developments such as the Trafford Centre in Birmingham, UK, the Basilica of Yamoussoukro on the Ivory Coast and the new European Parliament building. Dramatic effects are not only achieved in large structures though. Coloured concrete is just as effectively used in architectural pavements, paving stones and internal flooring. Cementitious Floor Screeds Cementitious floor screeds, figure 1, first developed in Scandinavia, have become an integral part of the UK flooring and construction industry, but unlike the traditional resin floorings, cementitious systems cannot be pigmented to produce a vast variety of colours. However, research by Armorex Ltd in Suffolk has focused on producing bright, intensively coloured screeds in which the colour is consistent throughout the materials. Cemlevel is a revolutionary coloured cementitious self-smoothing compound containing metallic non-oxidising aggregate 5-10mm thick. Cemlevel produces a durable surface with an aesthetically pleasing coloured finish and has been implemented successfully in both industrial and commercial applications. |

| | Figure 1. Application of a self-smoothing floor screed using a convectional floor pump. | Methods for Adding Colour to Concrete Colour can be added to concrete in two basic ways - using coloured cement or by adding a colouring agent into the concrete or mortar during mixing. The colour is determined by the pigments selected, which are generally divided into two categories - natural and synthetic. Natural Pigments Natural pigments are made from mined ores such as carbon and manganese (blacks), chromium (yellows, reds, browns, greens), and cobalt spinels (blues). Synthetic Pigments Synthetic pigments meanwhile are made from iron salts, by-products of the steel industry or from scrap steel dissolved in acid and precipitated. The main colours are red, yellow and black. Permanent Colouring While careful selection of pigments (type and amount) helps to achieve the desired colour, exposing coloured aggregates incorporated in the mix gives a more permanent colouring system with both pigment and complementary aggregate colour, in turn minimising the effects of ultraviolet lights and other stains such as efflorescence. Stains on Concrete Stains, particularly white stains, take on a greater level of significance when they appear on coloured concrete compared with standard material. Efflorescence Efflorescence is the most common cause of colour fading in coloured concrete. It takes the form of white deposits commonly observed on the surfaces of concrete, mortar and brickwork of both buildings and block paving, figure 2. |

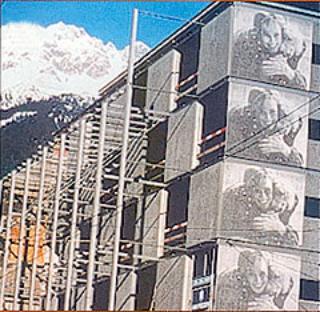

| | Figure 2. Lime weeping, a form of efflorescence. | Lime weeping and lime bloom are the most commonly observed forms of efflorescence - crystallisation of soluble salts is another. The difference between lime weeping and lime bloom is in their physical appearance, with lime weeping usually forming first as unsightly blemishes of hazy white layers, which become visible as the concrete begins to dry out, to produce thicker white crusts. Composition of Efflorescence and Its Evolution Professor John Bensted, Cement Technologist and visiting Professor at Birbeck College, London, gave a presentation at the SCI meeting on the ‘Chemistry of Efflorescence’, which detailed the chemical composition of efflorescence. ‘The white deposits are composed of calcium carbonate, normally in the form of calcite, and arise by the effects of aeration (hydration plus carbonation). These effects promote transport of ions like Ca2+ and OH- in solution through the structure to the external surface, where evaporation of water occurs and calcium hydroxide Ca(OH)2 is deposited. This quickly carbonates by reaction with moist air containing carbon dioxide CO2 to form calcite, which remains on the surface, giving the surface of coloured concrete an unsightly appearance,’ explains Bensted. The Effect of Efflorescence The effect efflorescence has on the visual appearance of many concrete structures has been a cause for concern for a long time. While almost unnoticeable on white concrete, as the depth of colours used increases, the effects of efflorescence on coloured structures is becoming rapidly unacceptable. Reducing the Effects of Efflorescence There is no known cure for both primary (occurs during the first few weeks as the concrete cures and dries out) and secondary (occurs during subsequent wetting and drying cycles) efflorescence. However, some manufacturers of decorative concrete products have found that using metakaolin, sometimes in combination with other measures such as lower water/cement ratios, blended cements and increased impermeability, can help reduce the effects of efflorescence. Screen-Printed or Photo-Engraved Concrete Despite the problems associated with coloured concretes, the versatility of the material means that the architect’s favourite medium remains unchanged. A new decorative concrete that is gaining the interest of architects in Germany, Switzerland and France is ‘screen-printed’ and ‘photo-engraved’ concrete, developed by French-based company Pieri. Using the Serilith system, a photograph or design is screen-printed, using a retarder, onto a polystyrene sheet as a layer of tiny dots. The photo-sensitive sheet is then placed into a mould ‘face up’ and the concrete is poured on top. Approximately two days later, the mould is stripped and the unit pressure-washed. By carefully selecting coloured aggregates and sands, a good reproduction of the photograph or design is obtained. This technique has been used to photoengrave animals onto the walls of the Hunting Association building in France, a wall of trees on the Stockholm Metro and repetitive photographic images covering the entire exterior of the Eberswalde Technical School Library in Germany. Figure 3 shows the mother and child image on the Mair clothing store in Innsbruck. The technique is not restricted to internal and external walls, it can also be used to create photographs or designs onto ceilings or floors. |

| | Figure 3. The Mair clothing store in Innsbruck with photo engraved panels on the side of the building. | Summary A few years ago, particularly in Europe, houses had to be made from white concrete and it was forbidden to alter the surfaces. Over the past few years the versatility of concrete has been realised and as architects and the construction industry discover what can be achieved with this material, concrete is becoming more visually interesting as a building material, and can now be seen as more ‘designer’ than ‘dull’. |