AZoM speaks with Professor Chris Howe about his research with cyanobacteria. These algae were able to power a microprocessor for an extended period of time in an exciting new breakthrough for natural energy production.

Please could you introduce yourself and your research background, as well as what inspired your latest study?

I’m a Professor of Biochemistry at the University of Cambridge, and I’ve studied photosynthesis throughout my academic career of nearly forty years. Our work has ranged from looking at the evolution of photosynthesis, through understanding the basic biochemical mechanisms underlying it, to exploiting it.

You were able to power a microprocessor with a strain of cyanobacteria. Why was this strain, Synechocystis, chosen, and how were you able to successfully power the microprocessor for a whole year (including times when it was dark)?

Synechocystis is a widely studied photosynthetic bacterium, also known as a cyanobacterium or a ‘blue-green alga’. Cyanobacteria are found nearly everywhere, and scientists have developed a wide range of experimental tools for analyzing Synechocystis and how it works. It’s harmless and easy to grow. It just needs sunlight to give it energy, so we were able to keep it running for a long time, just topping up water that was lost by evaporation.

Although the power produced is driven by photosynthesis, and therefore sunlight, in the dark the cells will metabolize compounds that they made in the light. That means they can continue to produce power in the dark.

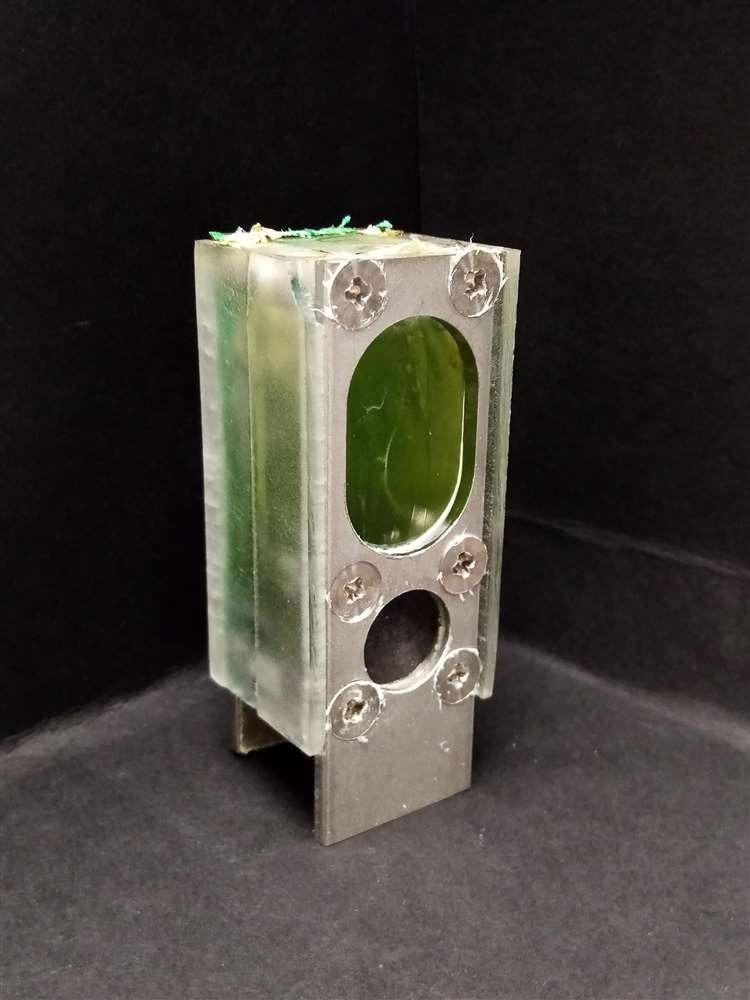

The mini device powered by algae. Picture: Dr Paolo Bombelli

Why have photosynthetic bacterial devices such as this not been successful before now?

We and others have successfully driven other things with power from these devices, such as environmental sensors and LEDs. This is the first time we have used it to drive a microprocessor and, as far as we know, no one has done that before. One of the additional novel features of our device was to use aluminum as an anode, which may help in power production.

How much power is this device currently able to provide, and what factors limit this?

We made the device as small as possible, while still being able to power the microprocessor. So the device on average only provided just over a microwatt of electrical power. That’s very small but enough to run the microprocessor. Larger devices will produce more power, and factors limiting the power will include external ones, such as the amount of sunlight, and internal ones, such as what fraction of sunlight the organism harvests can actually be turned into electrical power.

Prof Christopher Howe, left, and Dr Paolo Bombelli, both from the Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, with the algae and the device it has powered. Picture: University of Cambridge

How scalable is this technology? What advances are required to integrate such technologies into daily life?

One of the questions will be whether we scale by making larger devices, connecting many together, or both. We’d also like to find out if we can manipulate the algae to produce more power. The answers to those questions will help us know how scalable it is. Scaling up is often a challenge in science.

With a climate and resource crisis looming, how important is it that researchers focus their efforts on developing novel sustainable energy practices?

It’s very important – and we need to recognize that we need multiple solutions for different locations. For example, a system that generates a lot of power and can run a grid may not be of any use in isolated places that don’t have that grid infrastructure. In those places, smaller, distributed systems are likely to be better.

What is personally the most exciting part of this research for you?

I’ve always been fascinated by photosynthesis - as a child I used to do experiments extracting pigments from plants growing in the garden. It’s exciting to study an important natural phenomenon (the production of extracellular current from photosynthetic microorganisms) and also to try to implement it.

What are the next steps for you and your research?

We want to understand more about how the algae export electrons, and how we might be able to enhance export.

We also want to try some ‘real-world’ applications. We think these devices could be very useful in education. They are not difficult to make but could be used to help pupils in schools understand more about the important process of photosynthesis as well as learn more about renewable energy and environmental concerns.

More Interviews from AZoM: Creating Sustainable Textiles From Seaweed

About Professor Chris Howe

I’ve worked at Cambridge University throughout my academic career, and have been a Professor of Plant and Microbial Biochemistry in the Department of Biochemistry since 2005. I’m also a Fellow of Corpus Christi College in Cambridge. My work has always concentrated on photosynthesis – the evolution and function of photosynthetic systems and how we can exploit them. As well as the work described here, we are particularly interested in dinoflagellate algae, which underpin coral reefs. We aim to understand more about why their relationship with coral hosts can break down, leading to coral bleaching.

I’ve worked at Cambridge University throughout my academic career, and have been a Professor of Plant and Microbial Biochemistry in the Department of Biochemistry since 2005. I’m also a Fellow of Corpus Christi College in Cambridge. My work has always concentrated on photosynthesis – the evolution and function of photosynthetic systems and how we can exploit them. As well as the work described here, we are particularly interested in dinoflagellate algae, which underpin coral reefs. We aim to understand more about why their relationship with coral hosts can break down, leading to coral bleaching.

https://www.bioc.cam.ac.uk/

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited (T/A) AZoNetwork, the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and Conditions of use of this website.