This article examines the field deployment of a portable ABB OA-ICOS trace gas analyzer to measure nitrous oxide emissions from cattle enclosures.

Image Credit: Shutterstock/BOULENGER Xavier

Introduction

Understanding anthropogenic emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O) – also known as laughing gas – is of key concern to the environmental scientific community. N2O is an important greenhouse gas with an atmospheric lifetime of over 100 years. However, the chemical process that is used to remove it from the atmosphere has been found to also destroy the ozone.

The atmospheric concentration of N2O has significantly increased over recent decades, largely due to the heavy use of synthetic fertilizers designed to increase crop yields. Manure is another crucial anthropogenic source of N2O emissions that requires careful management.

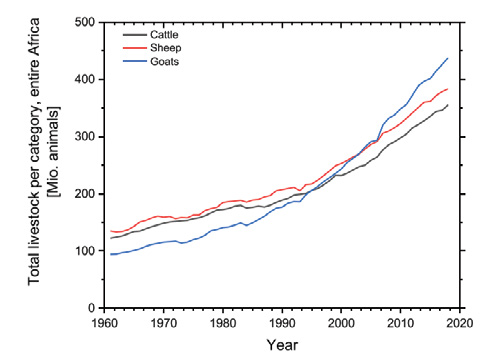

Over the last six decades, there has been a substantial growth in the livestock population in Africa, which now comprises more than 20 % of the global population of cattle, sheep, and goats. These livestock are typically allowed to roam during the day for grazing, and at night, they are held in temporary enclosures called bomas.

Livestock grazing leads to a significant concentration of nitrogen (N) in excreta, as only 7 % to 33 % of the ingested N is metabolized, and the remaining is excreted as urine or dung. This change in N cycling is of high importance in the semi-arid and arid regions of Sub-Saharan Africa, where local pastoralist communities do not tend to use manure for fertilizer, as they do not produce crops in large amounts.

Bomas are periodically abandoned when communities decide to move, driven by changes in resource availability. As a consequence, manure left behind piles up, and over the years, this can grow to several meters in height. These patches of fertile soil, rich in carbon (C), N, and phosphorous (P), contribute to the spatial diversity within savanna landscapes, promoting enhanced plant biomass and improved forage quality for many decades.

Even years after its abandonment, bomas can still be visible on the landscape as grassy glades that attract wildlife, particularly large herbivores that deposit dung and maintain bomas as nutrient hotspots for thousands of years. Yet, the role of bomas as potential focal points for N2O emissions within the landscape has yet to be investigated.

The article "Livestock enclosures in drylands of Sub-Saharan Africa are overlooked hotspots of N2O emissions" describes a study conducted by an international team of scientists.1 They measured fluxes at abandoned bomas spanning different ages and compared them with adjacent savanna sites in Kenya. The study aimed to investigate the hypothesis that bomas serve as significant spatial hotspots for N2O emissions in semi-arid and arid regions of Sub-Saharan Africa over decades.

Measurements From Different Locations

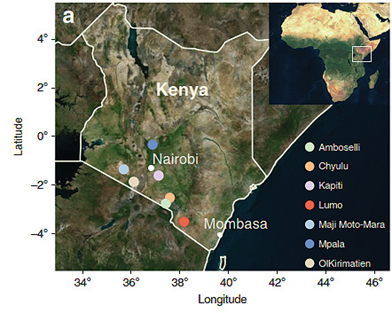

N2O fluxes were measured at seven locations across Kenya for 46 boma sites, differing in age after abandonment (0.1 to 40 years) and at 22 adjacent savanna sites. In total, 257 flux measurements were undertaken during both the wet and dry seasons in 2018-2019. Gravimetric data of the water content and soil temperature were used to complement the flux measurements.

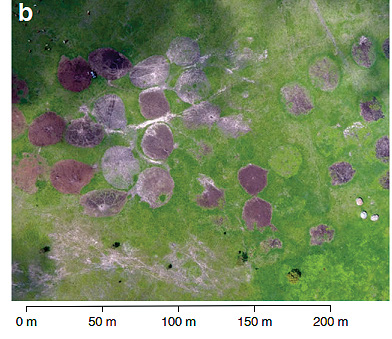

Location of study sites and aerial photos of bomas.

Image Credit: Butterbach-Bahl et al.

N2O emissions from bomas were assessed using the fast-box chamber method employing an ABB Off-Axis Integrated Cavity Output Spectroscopy (OA-ICOS) N2OM1 portable N2O /CH4 analyzer (former model 909–0041). A gas-tight vented chamber was placed on the ground on foam frames for 4 to 7 minutes. Throughout this period, air samples were extracted from the chamber’s headspace and pumped into the analyzer before being reintroduced to the chamber. This process enabled continuous monitoring of changes in headspace N2O concentrations every five seconds, providing a running average over the sampling duration.

Scientists are collecting flux measurements with an OA-ICOS portable N2O/CH4 analyzer.

Image Credit: Karlsruhe Institute of Technology

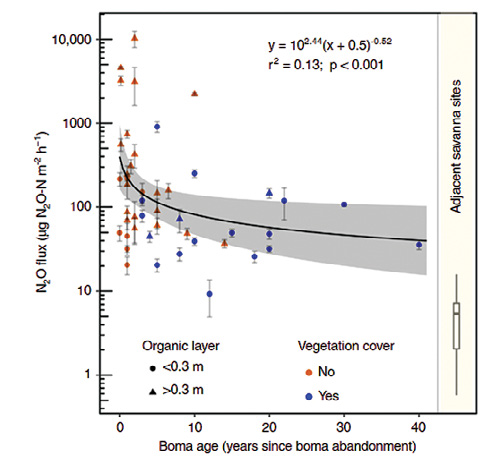

The results show that abandoned bomas continue to serve as active hotspots for N2O emissions for at least four decades, maintaining levels approximately one order of magnitude greater than those observed in the surrounding savanna.

Exponential cumulative decline of N2O fluxes for 40 years following boma abandonment.

Image Credit: Butterbach-Bahl et al.

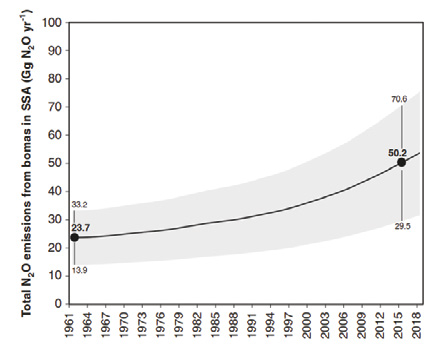

Top: Changes in total livestock numbers on the African continent since 1961. Bottom: Changes in N2O source strength of abandoned bomas since 1961.

Image Credit: Butterbach-Bahl et al.

In summary, the survey findings confirm that bomas constitute an overlooked source of atmospheric N2O on the African continent, with emissions more than doubling due to the increase in livestock populations in semi-arid and arid environments over the past six decades.

The authors conclude that N2O emissions from bomas have been largely disregarded and currently contribute around 5 % of the total anthropogenic N2O emissions across the African continent. They propose a need to refine current methods for estimating N2O emissions from livestock kept by pastoralists in semi-arid and arid landscapes in Sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere to account for abandoned bomas. Additionally, they recommend considering straightforward yet effective manure management strategies to mitigate the environmental nitrogen footprint associated with bomas.

References and Further Reading

- Butterbach-Bahl, K,. et al. (2020) Livestock enclosures in drylands of Sub-Saharan Africa are overlooked hotspots of N2O emissions. Nature Communications. doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18359-y

This information has been sourced, reviewed and adapted from materials provided by ABB.

For more information on this source, please visit ABB.