As well as organic structures, mineral structures also play an important role in living organisms. You don't even have to go as far as seashells or the artful silica scaffolds of diatoms; a glimpse into your own body will do.

Our bones and teeth are made of the mineral hydroxyapatite. Scientists try to imitate the processes of biomineralization in order to better repair such things as bones and teeth. A team led by Franklin R. Tay at the Georgia Health Sciences University (USA) and Ji-hua Chen at the Fourth Military Medical University (China) has now introduced a new approach in the journal Angewandte Chemie: the biomineralization of a collagen/silica hybrid material.

Biomineralization is a very complicated process that is not so easy to mimic. The silicate precursors required for the synthesis of the cell walls of diatoms are in a stabilized form, which prevents their uncontrolled polymerization. Special proteins then control the polymerization to make the highly complex structures of the resulting scaffold. Researchers would also like to control biomineralization processes to repair damaged teeth or to make synthetic cartilage and bone tissue. In order to culture bones, scientists would like to seed osteoblasts (bone building cells) from the patient's own body onto a substrate, where they would attach and multiply. This scaffolding would be implanted to help damaged bone, in cases of osteoporosis-induced or highly complicated fractures for example, to regenerate. Osteoblasts release collagen, calcium phosphate, and calcium carbonate as the basis for new bone material.

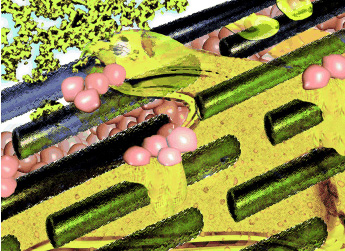

Collagen fibers would be an ideal substrate, but they are not solid enough for bone repair. The researchers once again turned to nature for inspiration: in glass sponges, a collagen matrix is one component of the silica scaffolding. Would it thus be possible to strengthen a collagen structure with silica (silicon dioxide)? Although many teams have previously failed in their attempts, the team led by Tay and Chen has now been successful.

They used collagen fibers as both a "mold" and a catalyst for the polymerization of the liquid phase of a silica precursor compound to make solid silica. The silica precursor is stabilized with choline to prevent an uncontrolled polymerization. This leaves enough time for the liquid precursor to fully infiltrate the space between the microfibrils of the collagen fibers before it polymerizes to form silica - one secret to the success of this new approach. After the polymerization the solid silica reflects the architecture determined by the collagen fibers. After drying, the original sponge-like, porous structure of the collagen fibers is maintained. In contrast to pure collagen, the scaffold of the hybrid compound is stable and could, the researchers hope, be used to repair bones.