Dec 5 2014

The Schuh Group at MIT is developing new tungsten alloys that could be used to substitute depleted uranium in structural military applications, such as projectiles. Depleted uranium is a potential health hazard.

The challenge was to create an alloy that is on par with uranium, which sharpens as it shears off material and sustains a pointed nose at the penetrator-target interface.

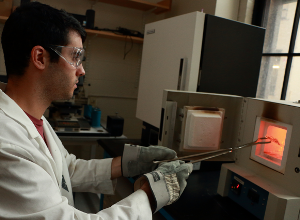

MIT graduate student Zack Cordero removes a vacuum-sealed glass ampoule from a box furnace operating at 1,100 degrees Celsius that is used to anneal metal powders. Photo: Denis Paiste/Materials Processing Center

MIT graduate student Zack Cordero removes a vacuum-sealed glass ampoule from a box furnace operating at 1,100 degrees Celsius that is used to anneal metal powders. Photo: Denis Paiste/Materials Processing Center

When compared to commercial tungsten alloys, a tungsten alloy with iron and chromium (W-7Cr-9Fe) is considerably stronger. MIT graduate student, Zachary C. Cordero, used a material that has high strength, high density, and low toxicity.

He deformed and compacted metal powders like tungsten-chromium powders to produce stronger metals having a nano-sized grain structure. These materials have unique properties, which can be used in various applications. The aim of the study was to make large objects with a fine grain size.

The metal powders are compacted in a sintering hot press for 1 minute at 1,200°C. On the other hand, high temperature and extended processing time can result in coarse grains with reduced mechanical properties.

Cordero was able to produce an ultrafine grain structure of 130nm in the W-7Cr-9Fe alloy and this was validated using electron micrographs. As well as hot-press sintering, the tungsten-chromium-iron alloy was also subjected to sub-scale ballistic tests. This powder processing method could possibly be used to create large samples with a dynamic compressive strength of 4GPa.

In addition, the strength of the metal alloy powders having nanoscale microstructures was also examined through laboratory experiments and computational simulations. These experiments demonstrated that chromium and tungsten with comparable initial strengths homogenize and create a stronger end product, while metal alloys such as zirconium and tungsten with large and dissimilar initial strengths tend to produce a weaker alloy.

The process of high-energy ball milling is one example of a larger family of processes in which you deform the material to drive its microstructure into a weird non-equilibrium state.

There isn't a good framework really for predicting the microstructure that comes out, so a lot of times this is trial and error. We were trying to remove the empiricism from designing alloys that will form a metastable solid solution, which is one example of a non-equilibrium phase.

Zack Cordero

MIT Graduate Student

Although the present study is focused on structural applications, the new powder processing route is also used in magnetic material production. Although this is conventional structural metallurgy, it can also be applied to new materials.