May 10 2019

Whether in industry, agriculture, or private households, chemicals are required in all places. However, their production necessitates a huge amount of energy. With a new kind of hybrid access, energy can be preserved in the double-digit percentage range contingent on the plant and process. The innovation took place in the team of Dr. Michael Bortz and Prof. Karl-Heinz Küfer at the Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Mathematics ITWM, for which they will be bestowed the Joseph von Fraunhofer Prize.

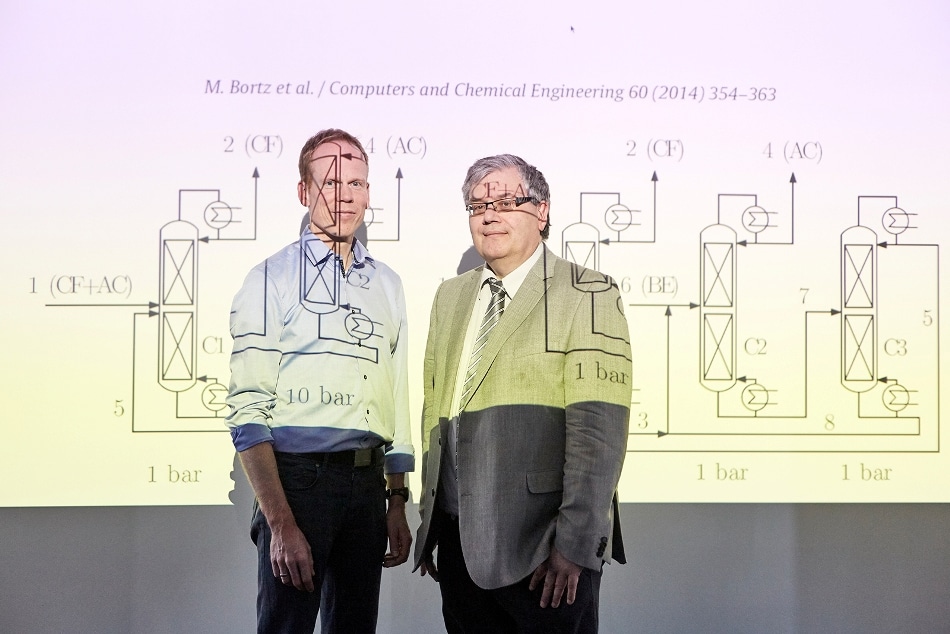

Dr. Michael Bortz (left) and Prof. Karl-Heinz Küfer of the Fraunhofer ITWM receive the Joseph von Fraunhofer Prize for the development of an analysis tool that can save energy in the double-digit percentage range. (© Fraunhofer/Piotr Banczerowski)

Dr. Michael Bortz (left) and Prof. Karl-Heinz Küfer of the Fraunhofer ITWM receive the Joseph von Fraunhofer Prize for the development of an analysis tool that can save energy in the double-digit percentage range. (© Fraunhofer/Piotr Banczerowski)

Plastics, fertilizers, detergents – these materials have become an essential part of a person’s daily lives. As varied as they are, they have one thing in common: they are made from specific basic chemicals that the chemical sectors manufacture in bulk. However, this involves a lot of energy: chemical production accounts for 20% of Europe's total commercial energy needs. If these can be decreased, this will protect the environment as well as the budgets of the companies. Trial and error can be eliminated – because then the product may not match the quality specifications and perhaps unsalable. The losses would be unexpected.

Analysis tool: significant energy savings

The team guided by Dr. Michael Bortz and Dr. Karl-Heinz Küfer from the Fraunhofer ITWM in Kaiserslautern has built a model that systematically describes the multifaceted processes. For this, they are being bestowed the Joseph von Fraunhofer Prize.

Our algorithms represent the processes realistically, so we can describe the production processes over the entire life cycle. This has already enabled us to save ten percent of the energy required for an existing production plant.

Dr. Michael Bortz, Physicist and Head of Department, Fraunhofer ITWM

The chemical group BASF and the Swiss chemical and pharmaceutical company Lonza Group AG are already using the software, which is available to hundreds of process engineers every day.

Firstly, a hybrid approach: Models and process data go hand in hand

For our analysis, we have brought two things together: Firstly, the physical laws that we have represented in a model – that is to say, the expert knowledge about the thermodynamic and chemical processes. And secondly, the data that various sensors determine about the measuring process, for example, temperature and pressure. We use these where no physical data is available.

Dr. Karl-Heinz Küfer, Division Manager, Fraunhofer ITWM

Thus far, such sensor data have already been used to track processes and to be able to react in a reasonable time if, for instance, temperature or pressure deviate. The team around the two scientists is using machine learning techniques to raise this "data treasure," including the training of artificial neural networks. Process data and models complement each other usefully.

The application potentials are not confined to the chemical sector: Rather, benefits can be anticipated wherever processes with several influencing factors have to be regulated – and cannot be defined just by measurements or process data. Going forward, according to the scientists' plan, the system should be able to work in real time.