Oct 4 2019

A cup of tea may be a cure for rainy days, but the soothing cup of the brewed beverage may also come with a dose of micro- and nano-sized plastics shed from plastic bags, according to researchers at McGill University.

While the possible health effects of ingesting these particles are currently unknown, the new research published in the American Chemical Society journal Environmental Science & Technology suggests further investigation is needed.

Plastic Teabags Releasing Micro- and Nanoplastics?

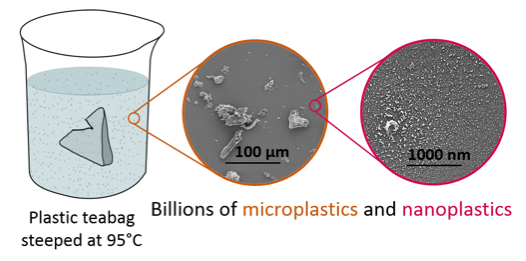

Over time, plastic breaks down into tiny microplastics and even smaller nanoplastics, the latter being less than 100 nanometers (nm) in size (a human hair has a diameter of about 75,000 nm). While scientists have previously detected microplastics in the environment, tap and bottled waters and some foods, McGill Professor of Chemical Engineering Nathalie Tufenkji and colleagues wondered whether recently introduced plastic teabags could be releasing micro- and nanoplastics into beverages during brewing.

To conduct their analysis, the researchers purchased four different commercial teas packaged in plastic teabags. The researchers cut open the bags and removed the tea leaves so that they wouldn’t interfere with the analysis.

Then, they heated the emptied teabags in water to simulate brewing tea. Using electron microscopy, the team found that a single plastic teabag at brewing temperature released about 11.6 billion microplastic and 3.1 billion nanoplastic particles into the water. These levels were thousands of times higher than those reported previously in other foods.

Anatomical and Behavioral Abnormalities Aquatic Organisms

The team also explored the effects of the released particles on small aquatic organisms called Daphnia magna, or water fleas, which are model organisms often used in environmental studies. The researchers treated water fleas with various doses of the micro- and nanoplastics released from the teabags.

Although the animals survived, they did show some anatomical and behavioral abnormalities. The first author of the study, PhD student Laura Hernandez says more research is needed to determine if the plastics could have more subtle or chronic effects on humans.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canada Foundation for Innovation and McGill University.