Feb 26 2020

A new technique for testing tiny aeronautical materials at extremely high temperatures has been recently demonstrated by scientists.

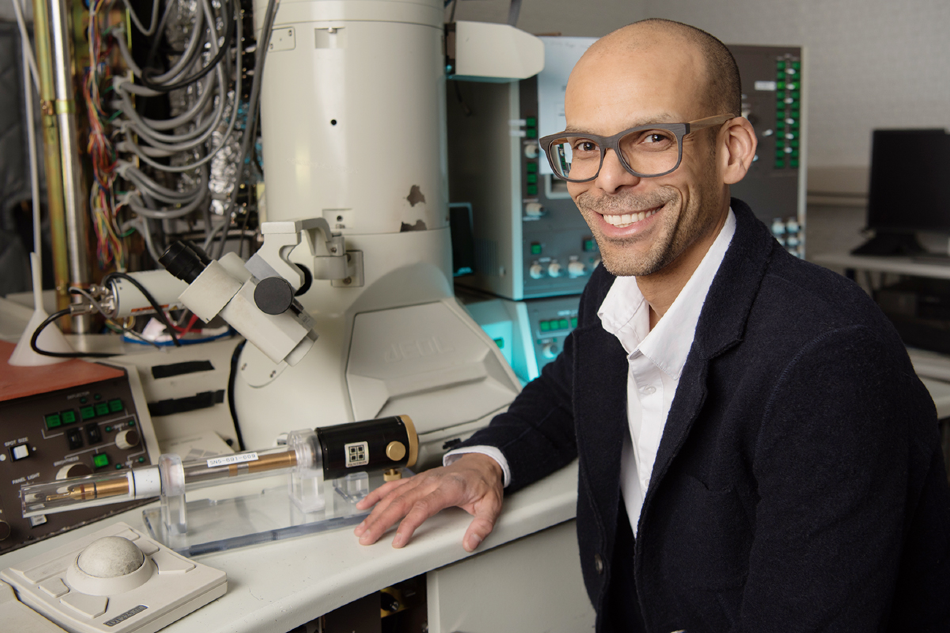

Materials science and engineering professor Shen Dillon uses electron microscopy and targeted laser heating for ultra-high temperature testing of aeronautical materials. Image Credit: Steph Adams.

Materials science and engineering professor Shen Dillon uses electron microscopy and targeted laser heating for ultra-high temperature testing of aeronautical materials. Image Credit: Steph Adams.

By integrating laser heating and electron microscopy, researchers can assess these microscopic materials relatively more rapidly and affordably when compared to conventional testing methods.

The latest study was carried out by Shen Dillon, a professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and colleagues from Sandia Laboratories. The study results were published in the Nano Letters journal.

Ten years ago, advances were made in aeronautical materials which involved many years of development and testing of costly and bulky models. Currently, engineers and researchers utilize micro-scale experimentation to help develop new materials and to figure out the physical and chemical properties that are responsible for causing material failure.

Micro-scale mechanical testing provides opportunities to break the materials down into their components and see defects at the atomic level.

Shen Dillon, Professor, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

To date, scientists have not been able to perform effective micro-scale materials tests at ultra-high temperatures that are experienced by crucial components at the time of flight.

Unfortunately, it’s really difficult to perform experiments with new materials or combinations of existing materials at ultra-high temperatures above 1,000 °C because you run into the problem of destroying the testing mechanisms themselves.

Shen Dillon, Professor, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Due to this temperature barrier, the advancement of innovative materials for commercial applications, like vehicles and rockets, has reduced. Rockets and vehicles need to be tested at temperatures that are much above the present research’s limit of “a few hundred degrees Celsius,” added Dillon. “The method we demonstrate in the paper will significantly reduce the time and expense involved in making these tests possible.”

The researchers’ ultra-high temperature test integrated two frequently used tools in a special way. Utilizing a combination of targeted laser heating and transmission electron microscope, the researchers were able to visualize and manage how and where the material exactly deformed at the maximum temperature possible prior to the evaporation of the sample.

We were able to bring the laser together with the mechanical tester so precisely with the TEM that we could heat the sample without overheating the mechanical tester. Our test allows you to grow a thin film of the material without any special processing and then put it in the microscope to test a number of different mechanical properties.

Shen Dillon, Professor, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

The latest study tested zirconium dioxide as proof of concept. Zirconium dioxide is utilized in thermal barrier coatings and fuel cells at temperatures as high as 2,050 °C, “a temperature well above anything that you could do previously,” added Dillon.

According to Dillon, the study will result in “more people using this technique for high-temperature tests in the future because they are much easier to do and the engineering interest is definitely there.”

Dillon is also affiliated with the Materials Research Lab at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The study was supported by the National Science Foundation and Army Research Office.