A recent study by Cynthia Permata Dewi and Putri Adhitana Paramitha published in the journal AIP Conference Proceedings explores the use of green roof solutions as part of a passive design strategy in residential buildings.

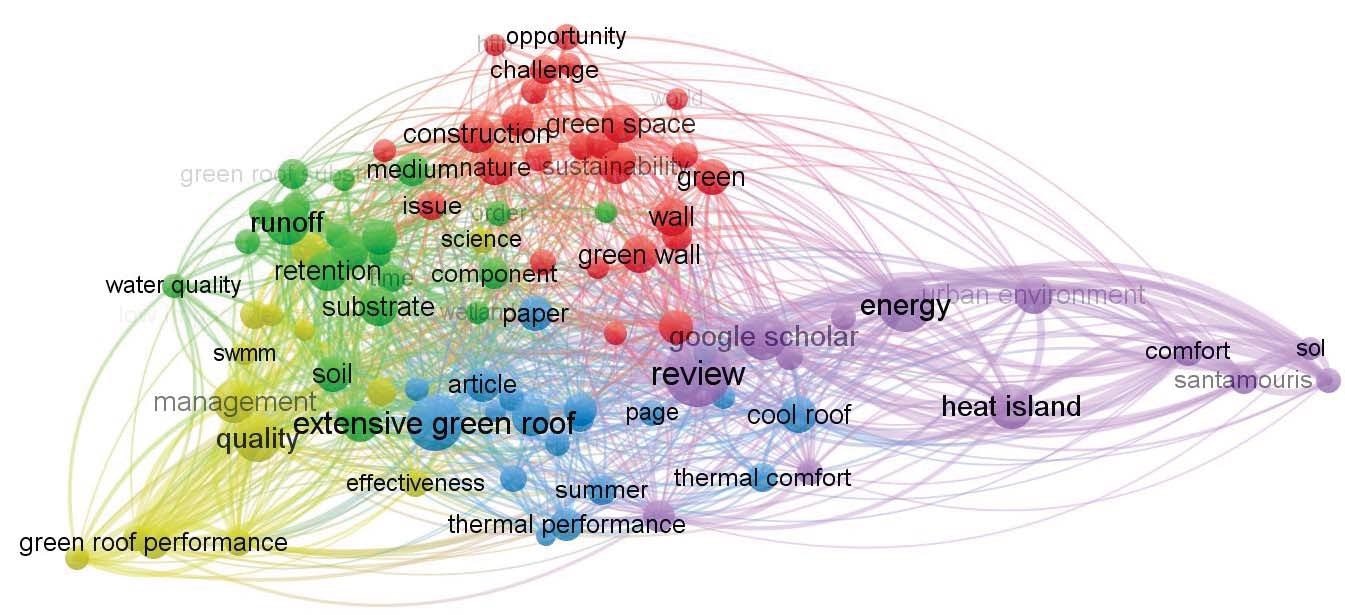

Research Gap Analysis. Image Credit: AIP Conference Proceedings

Research Gap Analysis. Image Credit: AIP Conference Proceedings

While difficult to define in precise terms, the concept of ‘thermal comfort’ has become a key factor in the design of buildings and other structures designed for human use.

Thermal comfort can be understood as referring to a person’s state of mind in relation to their temperature; for example, whether they are too hot or too cold. This can be affected by personal factors such as clothing, work-related factors such as strenuous activity, or environmental factors such as ambient heat or humidity.

Regulating thermal comfort is often an active process that requires the use of specific equipment and energy, for example, the use of air conditioning or heating systems in homes and workplaces.

These active approaches have both a cost and environmental impact, however, with the building sector estimated to utilize around 40% of overall global energy consumption.

The pressing need to consume less energy and address climate change is prompting the use of a more passive design strategy to help manage temperature and limit the need to use electrical equipment to achieve this.

Green roofs (also referred to as vegetative or eco-roofs) have become a popular option over recent years, seeing layers of vegetation planted over a waterproofing system that is installed on a flat or slightly slanted roof.

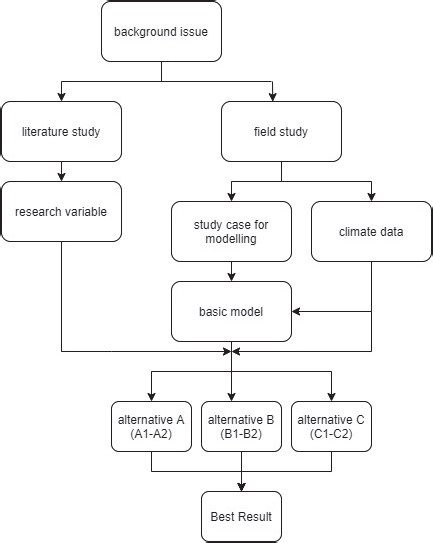

Research Flowchart. Image Credit: AIP Conference Proceedings

As well as helping to regulate thermal comfort, green roofs can also offer a number of other benefits including improving rainwater management, wastewater treatment, urban air quality, and helping to better manage noise pollution.

This innovative study used building simulation tools to conduct a series of virtual experiments, feeding in data around building dimensions and weather conditions from a number of sample buildings in a predominantly residential area in Blimbing, Malang-East Java, Indonesia.

Based on previous studies, the researchers categorized green roofs into three types: extensive, semi-extensive and intensive, depending on the type and height of vegetation involved.

The research identified a number of alternative models, highlighting the particular performance benefits of an intensive green roof installation. It was determined that a decrease in cooling energy demands of up to 21% could be accomplished by planting Tradescantia spathacea at a thickness of 0.7 meters.

The use of a semi-extensive green roof was found to be less effective, decreasing cooling energy demands by just 0.73%.

The research also looked to explore the specific factors that impacted the reduction of cooling energy demands, determining the height of the plant, leaf area index (LAI), and the plants’ potential to reduce the level of solar radiation reaching the building as key factors.

Residential Building Case Study. Image Credit: AIP Conference Proceedings

Studies have highlighted a range of other benefits of green roofs, including the effect of evapotranspiration, whereby a plant helps to cool nearby surfaces by retaining water inside the growing medium, an important factor in areas experiencing tropical temperatures and hot periods.

Thicker green roof layers typically offer more insulation and heat resistance, but there is an issue of additional weight being placed on the roof structure which must be considered.

Beyond their impact on helping to regulate thermal comfort, appropriately planned and installed green roofs offer a myriad range of other benefits.

There are clear economic benefits, with a recent valuation study from The University of Michigan highlighting that a 2000 square meter green roof could save up to $200,000 USD overall versus a conventional roof, two-thirds of which would stem from reduced energy costs.

As well as being visually appealing to many, an accessible green roof can also provide a valuable public amenity, particularly in high-density urban areas with limited access to green space.

Their impact on biodiversity is also notable, as green roofs offer the potential to provide a space for insects and birds with limited access to their natural habitat due to excessive urban development. In some examples, green roofs have also been used to promote urban agriculture, featuring herbs and vegetables that can be harvested for use by local communities and building occupants.

Dewi and Paramitha’s findings around the potential for green roofs to support thermal comfort add further weight to the use case for green roofs in a wide range of spaces, climates, and building types, as part of an overall passive design strategy with a focus on energy efficiency and sustainability.

References

Cynthia Permata Dewi, Putri Adhitana Paramitha, "An analysis of the efficiency of green roofs on cooling energy demand in residential building", AIP Conference Proceedings 2447, 030027 (2021) https://aip.scitation.org/doi/abs/10.1063/5.0072616

HSE, Thermal Comfort (n.d.) https://www.hse.gov.uk/temperature/thermal/index.htm

US National Parks Service, What is a Green Roof? (n.d.) https://www.nps.gov/tps/sustainability/new-technology/green-roofs/define.htm

US National Parks Service, Green Roof Benefits (n.d.) https://www.nps.gov/tps/sustainability/new-technology/green-roofs/benefits.htm

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.