From CSEMReviewed by Mychealla RiceJul 13 2022

The EU-funded macQsimal project, coordinated by CSEM as part of the EU’s FET Flagship on Quantum Technologies program, has now drawn to a close, after leading to some promising discoveries. For instance, engineers developed a new kind of miniature atomic watch that will soon hit the market. macQsimal was launched in 2018 to explore how quantum properties can be used to develop sensors with unprecedented precision and sensitivity, and to help establish a high-performance European industry in this field. The project’s closing ceremony was held at the University of Neuchâtel (UniNE), a key project consortium member, on 20–21 June through a symposium open to the public and an event held as part of the university’s Temps, Sciences et Société (Time, Science, and Society) conference series.

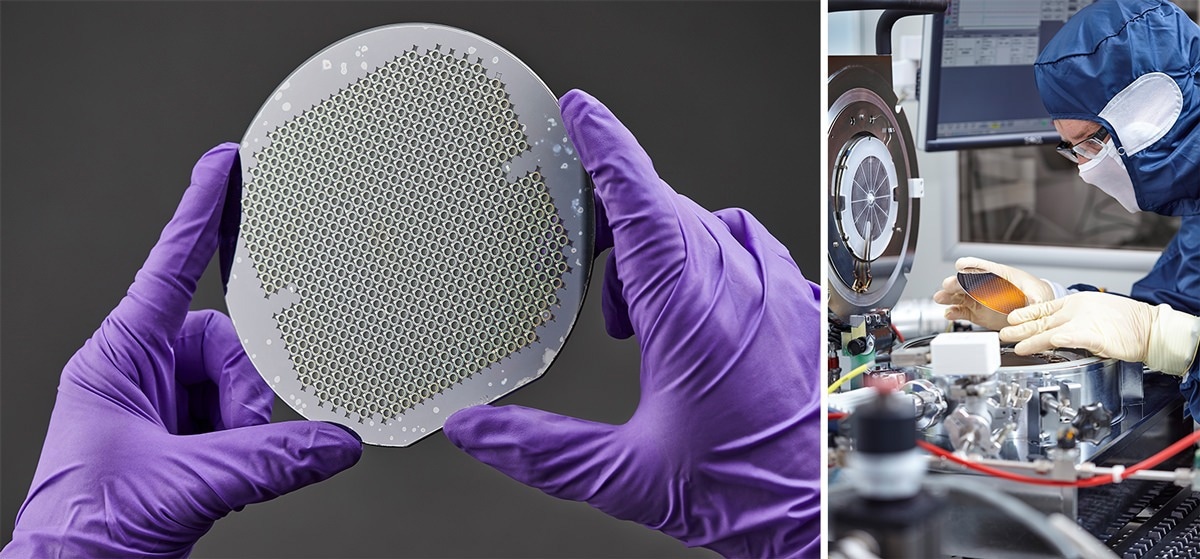

A wafer containing atomic-vapor MEMS cells, and the CSEM clean room where the cells were developed. Image Credit: CSEM

A wafer containing atomic-vapor MEMS cells, and the CSEM clean room where the cells were developed. Image Credit: CSEM

The first quantum revolution led to the transistors and lasers that form the basis of computers, smartphones and internet connections. Today, a second revolution is on the way thanks to advanced methods for manipulating the fundamental quantum properties of systems and materials. Engineers worldwide are racing to get a handle on these new methods in order to develop breakthrough technology in fields like healthcare, security, transportation, energy and environmental science.

Sensors that Push the Boundaries of Performance

macQsimal was carried out by a consortium of 14 partner organizations spanning the entire technology value chain, from fundamental research to industrial applications. Consortium members worked together to design next-generation, highly effective sensors based on atomic vapor cells, with a view to making the benefits of this technology available to the general public.

Transferring Technology in Switzerland by Turning Prototypes into Market-ready Products

The Swiss consortium members began transferring the technology developed under macQsimal to industry by creating a miniature atomic watch that runs on very little power. Most of the development work for the watch took place in Neuchâtel, from designing the watch’s core – consisting of MEMS cells developed by CSEM – and electronic control system to assembling the final product. Orolia Switzerland SA will market the watch in what’s shaping up to be a fast-growing industry with expanding demand for atomic watches.

“We began studying miniaturized atomic watches about 15 years ago, and now our work is leading to new products being marketed in our region,” say Christoph Affolderbach and Gaetano Mileti, a senior scientist and professor, respectively, at UniNE’s Time-Frequency Laboratory (LTF). “We intend to continue our research in order to maintain Neuchâtel’s leadership position in this industry, which is a strategic one for Switzerland.”

Mini Backup Generators

Atomic watches offer unique benefits for coordinating many essential public services like telecom networks, transportation systems and power grids. For now, these services rely on GPS signals and the Galileo satellite system – meaning that if there’s a signal interruption or attack, the services could be disrupted. However, if atomic watches are installed, they could take over and keep the services running for a few hours while the problem is being fixed. “Atomic watches could serve as a type of back-up generator in certain applications,” says Jacques Haesler, the macQsimal project coordinator and a senior project manager at CSEM.

An Uncertain Future

In addition to the miniature atomic watch, other prototypes that came out of macQsimal include quantum sensors with remarkable sensitivity for use in magnetometers and gyroscopes, for example. These instruments have potential in applications ranging from medical diagnostics to autonomous navigation. The prototypes were developed in close collaboration with research groups and companies based in neighboring European countries.

But the process of turning the prototypes into marketable products is on hold since Switzerland has been excluded from EU-funded research programs (following the break in negotiations on the country’s framework agreement with the EU). Switzerland provides the MEMS cells that form the core of the sensors.

The second stage of the FET Flagship on Quantum Technologies program has just attributed funding for the first set of technology transfer initiatives to industry – but it doesn’t include Switzerland.

“The Swiss federal government has announced some initial temporary measures to fill the funding gap caused by Switzerland’s exclusion,” says Haesler. “These measures will let Swiss researchers and businesses working on quantum technology continue with their R&D for the near term. But since they’ve now been sidelined, they won’t be able to keep working with organizations elsewhere in Europe. If we’re able to get back into EU-funded research programs quickly, we can make up for the lost time with as little collateral damage as possible.”