| If there’s one thing Europeans can agree on, it’s a good bottle of wine, whether it’s a vintage red or classic white. But how often have you opened a bottle of wine, only to find it smells like sweaty socks? According to industry figures, six to eight percent of wine is spoiled as a result of bad corks. This is the reason why a number of wine producers are now turning to synthetic corks, which give the sealing properties of real cork but do not harbour the compound that can cause the musty odour. Alternative Cork Materials The industry has seen a rash of alternative stoppers during the past few years, which while solving the problem of taint have been criticised for their ease of use and aesthetic properties. This has led to the development of a new generation of synthetic corks such as the Betacorque, an artificial cork that looks and feels like the natural product. Because of the availability of viable alternatives, the cork industry has had to admit there is a problem and is now investing large amounts of money into solving the problem of ‘corked’ wines. Natural Cork Natural cork is produced from the bark of a species of European oak tree. It grows to form tiny cells, each a 14-sided polyhedron. Strips are carefully removed and dried for six months. After a further three weeks, in which the strips are boiled and dried, the cork is finally cut into the traditional shapes. It’s during this process of harvesting and production that the cork can become contaminated, resulting in the development of ‘2,4,6-trichloroanisole’ or TCA, the main cause of ‘corked’ wines. Synthetic Corks Since arriving on the market in the early 1990s, synthetic corks have steadily developed an acceptance among wine producers, particularly those in the New World regions, and distributors such as UK supermarkets. Early efforts from companies such as Supremecorq were made from thermoplastic elastomers. The Betacorque Alternative Yet, until now no substitute has existed that retains cork’s desirable elastic qualities along with its traditional look and feel. A new artificial cork developed by UK company Betacorque (figure 1) offers a solution to this problem. ‘Over other synthetics,’ says David Beanland, Production Director of Betacorque, ‘its single advantage is that it retains the appearance of natural cork.’ |

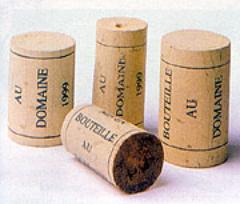

| | Figure 1. The Betacorpque, indistinguishable from natural cork.. | The Origin of Betacorque The original seed for the Betacorque was sown by Beanland’s co-partner, David Taylor, Technical and Product Director. Taylor and Beanland felt there was a need for a quality synthetic alternative, so they ‘reverse-engineered’ natural cork. ‘We set out to create a product that replicated cork,’ says Beanland, ‘and then applied it to the wine industry. We have ended up with a product that, as far as I can tell, is completely unrelated to any on the market at present.’ A large amount of research and development work has gone into developing the product, with the original investment coming from a UK syndicate of private individuals who, says Beanland, had the courage to ‘take it on and stick with if.’ Development of Betacorque Taylor invented and patented the Betacorque and spent the first two years of the project’s life developing it to a commercial standard. Early prototypes were tested by the wine industry and analytical houses, revealing a product that was much more permeable than it should have been - problems that were resolved by further development and testing. Now backed by investment from American-based moulding company Tuscarora, Betacorque has a commercially available product that it claims is virtually indistinguishable from the natural product and has extraordinary characteristics that ensure perfect sealing and extraction. Composition of the Betacorpque The Betacorque is made from a unique closed-cell polymer mixture, similar to that used in meat packaging. The bead material is expanded and injected into a radiator-like mould, which gives it its shape. The look and feel of natural cork is achieved by using food grade inks, wax treatments and printing, developed by the cork industry. ‘We try and make it as similar as possible to natural cork,’ says Beanland. ‘We can make them any colour on the outside: However, cutting open the Betacorque exposes its mottled brown cellular structure - one of the ways of differentiating it from the real thing. Colouration is applied to the surface of individual cells, which eliminates any white glare when the corkscrew is removed. Properties of the Betacorque Perfect sealing and extraction are made possible by a process the company has termed ‘dynamic elastification’, figure 1. When the material is under compression, for example when it is inserted into the bottleneck, it goes through a number of plastic and elastic deformations. The short, but powerful elastic stage gives the desired seal. However, the forces can never be excessive because the internal structure adjusts to absorb unwanted forces. Extraction from the bottle can be done with any normal corkscrew, using the same amount of force required to remove the natural product. |

| | Figure 2. On insertion of the Betacorque, it undergoes a process called dynamic elastification whereby its internal structure is transformed permanently to a shape that matches the bottleneck. | Size Ranges for the Betacorque The Betacorque can fit bottlenecks up to 19.5mm in diameter - used in high quality wines. Similarly it can be used at lengths up to 50mm. Disadvantage of the Betacorque The only disadvantage associated with the Betacorque is the modifications it requires to cork insertion machines, says Beanland. However, he believes this cost will easily repay itself. Target Markets Due to the need for testing in real time, the initial target market for the Betacorque is for wines that are bottled and drunk within a period of one month to a year, at a cost of between five to eight pence per unit. This is favourable with costs of up to 25 pence per unit of natural cork. ‘There will be certain price points beyond which synthetic corks won’t be attractive,’ says Beanland. ‘We won't touch some sectors because we can't sell our product for tuppence. Our typical user is a good quality wine producer, producing wines at £4.50 to £5.00 per bottle, who are receptive to new technology.’ Market Acceptance Two European wine producers are currently using the Betacorque to bottle their wines - Pallavicini in Italy, and Foxwoods in France. Both companies currently sell their wines in the UK and throughout mainland Europe, but Betacorque closed bottles are not yet being bought into the UK. Beanland believes supermarkets will be the biggest drivers of change in the UK. ‘They wield a lot of power,’ he says. Beanland thinks that the synthetic cork market is very buoyant at the moment. At the recent London Wine Fair at Olympia, London, the Betacorque was exhibited properly for the first time. ‘The stand was busy for three days,’ says Beanland. ‘We took in the region of 70 serious enquiries.’ As a result Betacorque is now in discussions with some of the major global players in the wine industry - the company has also received some interest from the port industry. Divided Opinoins So, could alternative closures see the demise of natural cork? Tom Forrest, Wine Development Manager at Vinopolis, London’s visitor attraction dedicated to wine, doesn’t think so. Only three of the 150 wines housed at Vinopolis are bottled using synthetic corks. ‘These new corks are coming along at a time when corked wines are becoming less common,’ says Forrest. ‘They do much more testing, so more corks are rejected.’ The Natural Cork Industry Fights Back Instead of just sitting back and watching its market share demise, the cork industry has started to fight back. It’s taking measures such as increasingly strict quality control and investment into scientific research, in order to make TCA a thing of the past. Developments in Naturals Cork Processing INOS II – Pressure Treatments Some of the world’s largest cork producers are now spending considerable amounts on research into TCA. For example, Amorim spends approximately US$1 million annually on research to solve the problem of cork taint. They have developed a process called INOS II, which supposedly eliminates TCA from cork disks by submerging and subjecting them to varying pressures in what is known as hydrodynamic extraction. INOS II has been used on cork disks for Amorim's champagne corks for several years, and the company is now testing it on corks for still wines. DELFIN - Microwave Treaments Work by the Neustadt Research Institute, Portuguese cork producers Juvenal Ferreira da Silva and Francisco, and the German cork distributor Ohlinger has created a microwave process that virtually eliminates cork taint. Known as DELFIN (direct environmental load focused inactivation), the process uses microwaves to kill TCA-producing microbes, which unlike washing is said to prevent TCA production throughout the cork. However, further research by the Australian Wine Research Institute has cast doubt on the effectiveness of DELFIN after finding no significant difference in the incidence of TCA taint in corks supposedly treated with the DELFIN process. Summary Despite the problem of taint, only the more modern wine producers seem keen to switch to synthetics. The market for alternative closures is predominantly in New World wines from countries such as America and Australia. For example, Californian winemaker St Francis bottles all its wines with synthetic corks. `Top quality wines have an image of quality and heritage; explains Forrest. `It will take a long time for them to think about using new products. New World wines don’t have this baggage, so are looking for alternatives because they know there’s a problem.’ Unlike natural cork, synthetic closures are an unproven technology and many are unsure of their effects on wines that are designed to mature for a longer period. Also, there is still a sense of ceremony attached to pulling a real cork out of a bottle. ‘Some people you will never convince,’ explains Beanland. ‘But the market is huge so you don’t need to convince everyone.’ At this point in the development of the cork industry, it’s down to personal preference whether it’s natural or synthetic. Purists argue that only natural cork can truly age and preserve a wine, while those who have to suffer the cost and inconvenience of corked wines believe it’s time for change. With all the research going on, wine drinkers around Europe will soon be able to make this choice for themselves. |