AZoM speaks with Dr. Kaalan Johnson and Dr. Seth Friedman from Seattle Children's Hospital. 3D printing has many uses at the hospital, from training purposes, to use in surgery, to aiding explanations of procedures to patients and their families.

Can you give our readers more information about how 3D printing is implemented at Seattle Children's Hospital?

3D printing is used across Seattle Children's for clinical care, training, education and engineering parts. Complex surgical care provides a great example of personalized medicine in action at Seattle Children's Hospital.

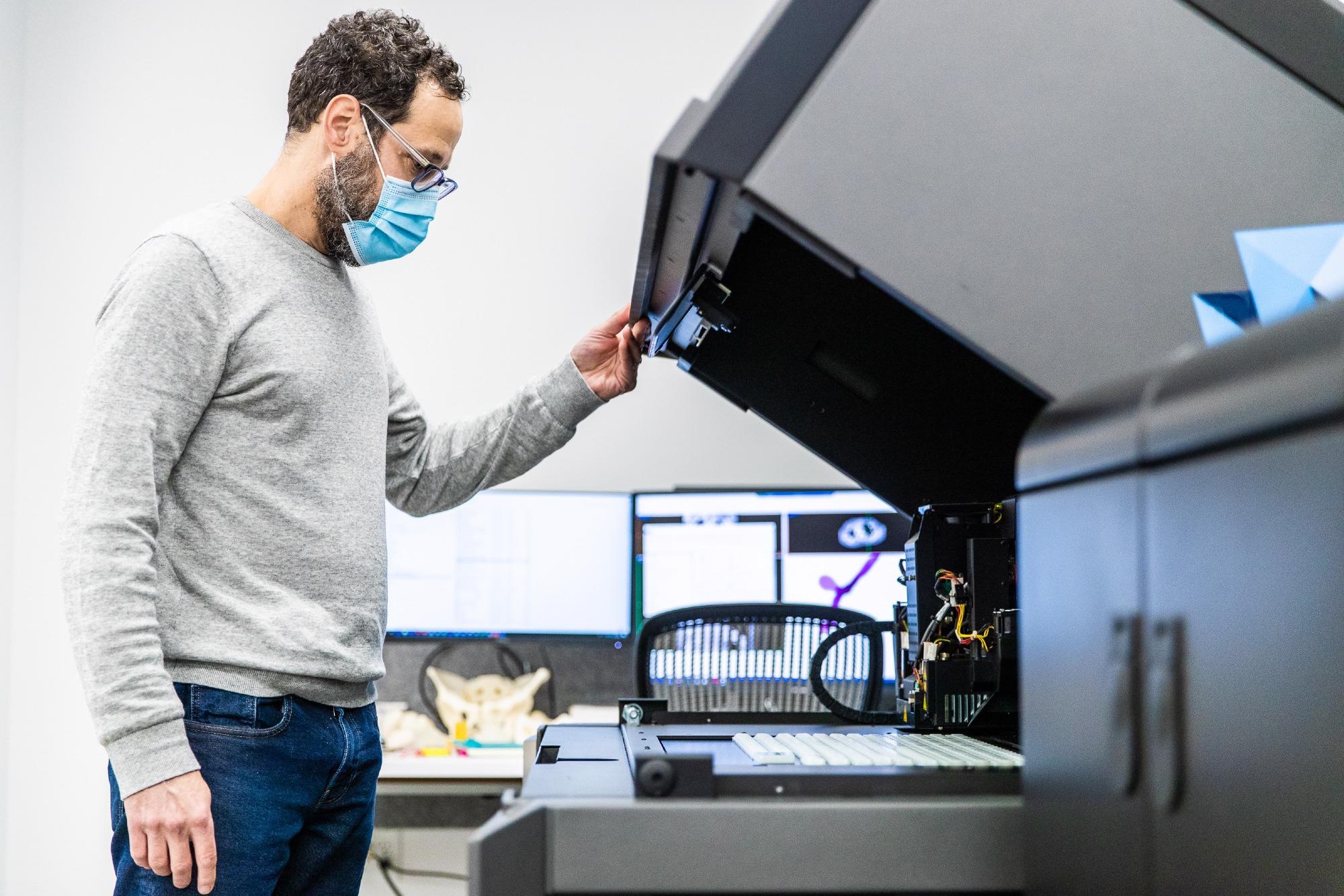

Dr. Friedman preparing a 3D printer at Seattle Children's Hospital

How can 3D printing be used to train medical students and what are some of the benefits?

Slide tracheoplasty is a relatively rare procedure where a narrow section of airway is divided and the healthy trachea is slid together to enlarge the airway. It provides a great example of how we are using models for training and how they can be broadly deployed elsewhere.

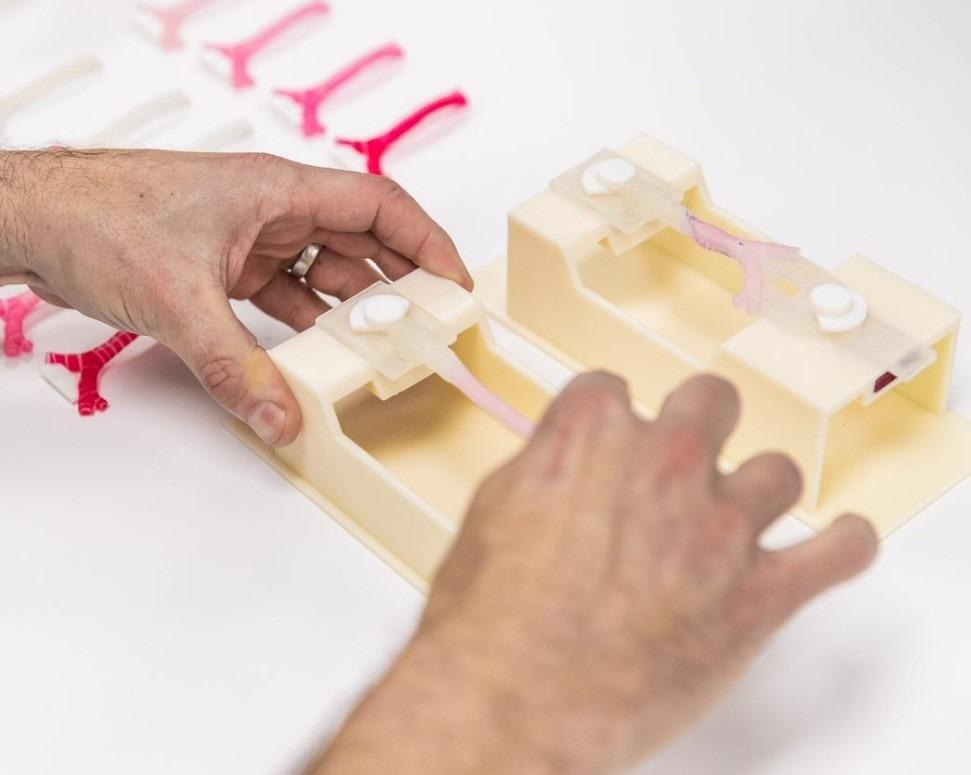

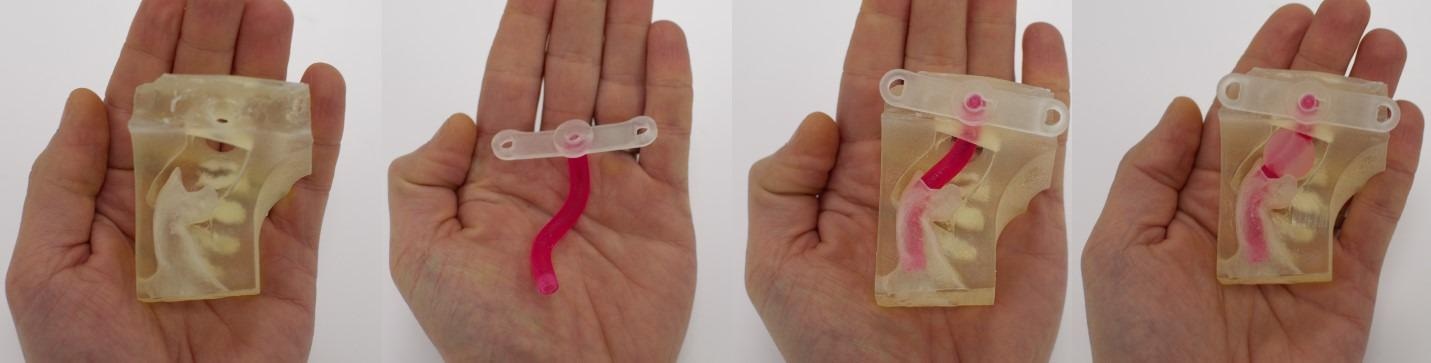

Given most trainees will have limited experience with this technique within their residency/fellowship, they have little choice but to "learn on the job" when cases present within their professional practice or perhaps use non-human models for simulation. Having a library of cases here, we have created a curriculum around J750 printed airways and an adjustable trainer box so that anyone can learn and practice the important variations (see Fig 1).

It has led to research too, with a current fellow Clare Richardson MD, studying how varying the surgical approach (cut angle and position) can impact what we think of as the goal outcome, a healthy airway that has not been shortened any more than needed and is maximally open.

Example airway with continuous cartilage sleeve before surgery (top image) and post-slide (bottom image). The multi-layered printed construct allows the separate components to be represented by different material properties (hardness, elasticity, color, and structure).

Can you give our readers more insight into your partnership with Stratasys?

One of the benefits of having a research relationship with Stratasys is that we can help collaboratively envision the future of 3D printing related to pediatric medicine. Not to state the obvious, but children are small and underdeveloped. This means when 3D printing a pelvis and femur, you need to be able to mimic unique developmental features like growth plates and connective tissue/skin elasticity that are not always straightforward to achieve.

Whereas, in diseases, there are many other details to include. Right now, we can modify some aspects of the printing process with the DAP to approximate these goals, but much more capacity/flexibility is coming soon.

Can you describe the process of manufacturing a 3D printed heart?

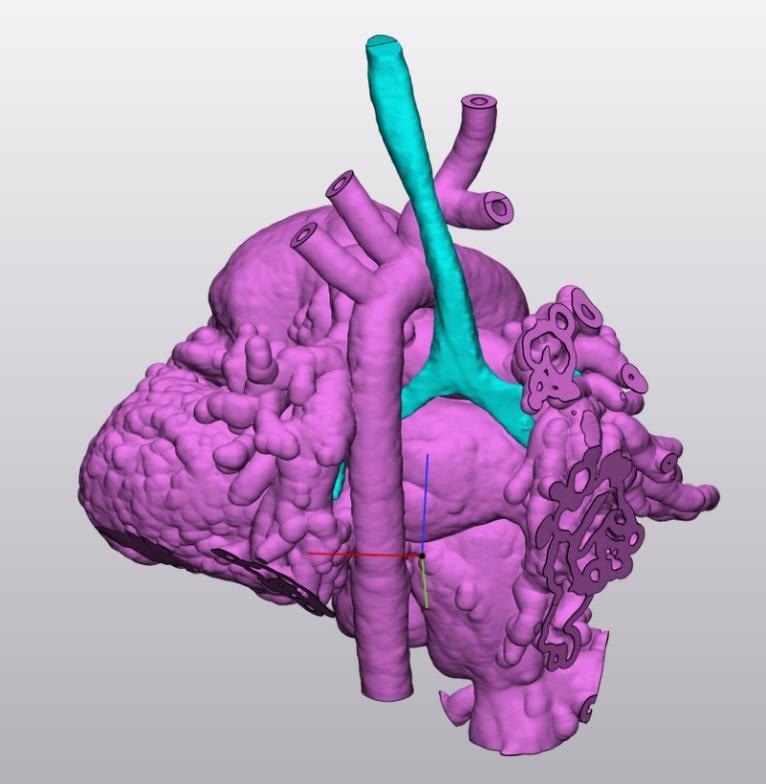

3D printing hearts is much like printing other biological structures. It starts with an optimization of the imaging needed for visualization. For a complex case, such as a child with heart and airway abnormalities, this might require adding together data from an endoscopy, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging.

The first step in making a printed model is image processing to generate discrete surfaces for each structure of interest (e.g., heart, airway, spine, esophagus, ligament) and adding unique labels to accentuate dynamic or defect features. The model is then validated by radiologists/the clinical team and a test print is performed to ensure that the material choice is optimal.

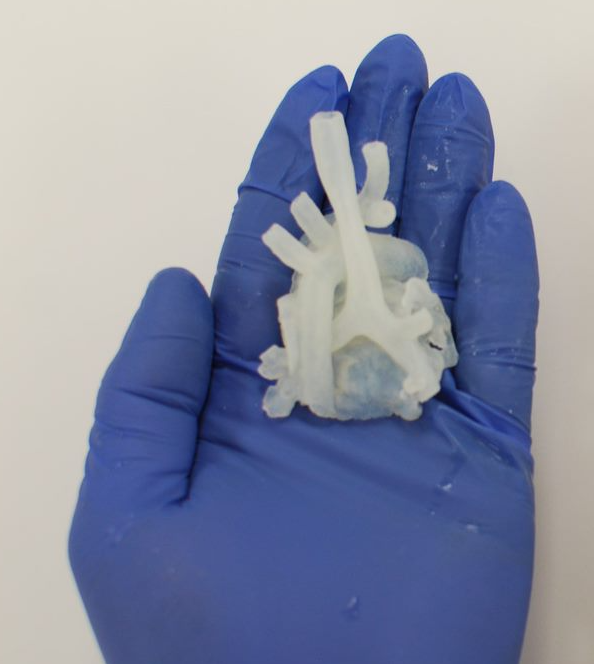

Though we have developed recipes for many tissues, materials do not always "feel" the same as they get thicker. Car tire rubber seems very hard, however if it was only 1 mm thick it would feel quite soft like a somewhat stale gummy candy. Given an airway printed with a 0.7 mm wall will feel much more malleable than one at 1.2 mm, our goal is to make the model as close as possible to the likely patient's tissues.

An example of heart/airway print for surgical slide practice. Although materials appear similar, the heart is printed in a construct to simulate myocardium and the airway is multi-layered. While visual differences can be helpful for educational models, many practice models prioritize tissue properties and feel.

How can the 3D models help to explain procedures to patients and their families?

While anatomy and surgical process is an easy language spoken by the surgeons, there is no doubt that translating this information to the patient can be challenging. Having a physical model provides a bridge to understanding their child's condition and sharing this information with their family/loved ones who make up their broadly defined care team. Sometimes these objects become lasting reminders of their care journey, an embodiment of what we strive to do at Seattle Children's Hospital every day, which is to provide hope, care and cures.

Example printed model showing how a custom tracheostomy tube would fit.

What are some of the most common procedures that 3D printed components are used in?

At Seattle Children's Hospital, 3D printing is the tip of our image processing iceberg which spans many types of 2D/3D/4D quantification and dynamic modeling. The most common procedures are in Otolaryngology (airway procedures, temporal bone drilling, skull base/tumor removal, custom tracheostomy tubes, vascular anomalies procedures), Craniofacial (facial/skull remodeling), Cardiology (baffle surgeries), Orthopedics (pelvis/long bones), and Neurosurgery (vascular cases/tumor/epilepsy). That said, if a complex procedure can benefit from having a physical model, our Custom Care service will make it happen.

When operating on children, what are some of the benefits that 3D printing can provide compared to traditional surgery techniques?

Some of the immediate benefits of having patient-specific models relate to practice and communication. For example, having five surgeons practice an upcoming procedure on an individual patient model and collaborate on their thinking about decision-points to reach a cohesive plan is an x-factor that will change medicine. Being able to print realistic anatomy across all systems is a game-changer for traditional approaches of cadaver or animal models.

As described above, this will help to develop better approaches, devices and simulators that can represent a much broader range of pathology over time.

Dr. Johnson speaking with a patient at Seattle Children's Hospital

Is the team at Seattle Children's Hospital looking to implement 3D printing in any other areas that it is not yet used in?

The future of 3D printing at Seattle Children's fits into our larger goal of bringing engineering solutions to provide the most cutting-edge surgical care possible.

Where can readers find more information?

More information and updates from the hospital can be found here.

About Dr. Kaalan Johnson

Dr. Johnson is the Surgical Director of the Aerodigestive Program, Director of the Voice Program, and practices at Seattle Children's Main Campus, North Clinic, and Bellevue Clinic and Surgery Center. He is an Associate Professor of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery at the University of Washington School of Medicine. He is a native of the northwest, but did his medical school in southern California and residency in Virginia before completing a fellowship in pediatric otolaryngology and first faculty position at Cincinnati Children's Hospital in Ohio.

He began working at Seattle Children's Hospital in 2013 and started seeing patients with complex airway, breathing, and swallowing problems in the Aerodigestive Clinic in 2014. Additional clinical interests include Tracheostomy / Airway Reconstruction, Voice, Exercise Induced Laryngeal Obstruction, Complex Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Nose & Sinus Surgery, and Ear Surgery. He has a long-term interest in medical simulation, and in addition to 3D Printing and Virtual Surgical Planning projects, he directs multiple simulation-based courses, and collaborates with the WWAMI Institute for Simulation in Healthcare (WISH) at the University of Washington.

He lives with his wife, three children, and their dog, and enjoys wakeboarding, snowboarding, and any other adventure he can do with his kids, as well as all types of music.

About Dr. Seth Friedman

Behind the scenes creating the digital and printed models and serving as one of many champions of Seattle Children’s new service called Custom Care is Dr. Seth Friedman. Dr. Friedman also oversees the Radiology Clinical Research Imaging Core, a resource serving intramural, extramural, and industry studies flowing through Seattle Children's, and conducts research across a range of diseases.

Behind the scenes creating the digital and printed models and serving as one of many champions of Seattle Children’s new service called Custom Care is Dr. Seth Friedman. Dr. Friedman also oversees the Radiology Clinical Research Imaging Core, a resource serving intramural, extramural, and industry studies flowing through Seattle Children's, and conducts research across a range of diseases.

When Seth is not making 3D models, printing things, writing code, running in and out of the operating room, and carving/casting sculpture, what he enjoys most is trying not to get too lost while bike-touring in the forests of the northwest.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited (T/A) AZoNetwork, the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and Conditions of use of this website.