Mar 31 2009

The power of magnetism may address a major problem facing bioengineers as they try to create new tissue -- getting human cells to not only form structures, but to stimulate the growth of blood vessels to nourish that growth.

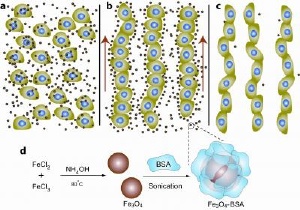

The process of forming cell chains using magnetic particles is shown in this photo. Credit: Duke University/Case Western Reserve University/University of Mass. Amherst.

The process of forming cell chains using magnetic particles is shown in this photo. Credit: Duke University/Case Western Reserve University/University of Mass. Amherst.

A multidisciplinary team of investigators from Duke University, Case Western Reserve University and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst created an environment where magnetic particles suspended within a specialized solution act like molecular sheep dogs. In response to external magnetic fields, the shepherds nudge free-floating human cells to form chains which could potentially be integrated into approaches for creating human tissues and organs.

The cells not only naturally adhere to each other upon contact, the researchers said, but the aligned cellular configurations may promote or accelerate the creation and growth of tiny blood vessels.

"We have developed an exciting way of using magnetism to manipulate human cells floating freely in a solution containing magnetic nanoparticles" said Randall Erb, fourth-year graduate student in the laboratory of Benjamin Yellen, assistant professor of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science, at Duke University's Pratt School of Engineering. "This new cell assembly process holds much promise for tissue engineering research and offers a novel way to organize cells in an inexpensive, easily accessible way."

Melissa Krebs, third-year biomedical engineering graduate student at Case Western and Erb's sister, co-authored a paper appearing online in advance of the May publication of Nano Letters, a journal published by the American Chemical Society.

"The cells have receptors on their surfaces that have an affinity for other cells," Krebs said. "They become sticky and attach to each other. When endothelial cells get together in a linear fashion, as they did in our experiments, it may help them to organize into tiny tubules."

The iron-containing nanoparticles used by the researchers are suspended within a liquid known as a ferrofluid. One of the unique properties of these ferrofluids is that they become highly magnetized in the presence of external magnetism, which allows researchers to readily manipulate the chain formation by altering the strength of the magnetic field.

At the end of the process, the nanoparticles are simply washed away, leaving a linear chain of cells. That the cells remain alive, healthy and relatively unaltered without any harmful effects from the process is one of the major advances of the new approach over other strategies using magnetism.

"Others have tried using magnetic particles either within or on the surface of the cells," Erb said. "However, the iron in the nanoparticles can be toxic to cells. Also, the process of removing the nanoparticles afterward can be harmful to the cell and its function."

The key ingredient for these studies was the synthesis of non-toxic ferrofluids by colleagues Bappaditya Samanta and Vincent Rotello at the University of Massachusetts, who developed a method for coating the magnetic nanoparticles with bovine serum albumin (BSA), a protein derived from cow blood. BSA is a stable protein used in many experiments because it is biochemically inert. In these experiments, the BSA shielded the cells from the toxic iron.

"The other main benefit of our approach is that we are creating three-dimensional cell chains without any sophisticated techniques or equipment," Krebs said. "Any type of tissue we'd ultimately want to engineer will have to be three-dimensional."

For their experiments, the researchers used human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Others types of cells have also been used, and it appears to the researchers that this new approach can work with any type of cell.

"While still in the early stages, we have shown that we can form oriented cellular structures," said Eben Alsberg, assistant professor of Biomedical Engineering and Orthopedic Surgery at Case Western and senior author of the paper. "The next step is to see if the spatial arrangement of these cells in three dimensions will promote vascular formation. A major hurdle in tissue engineering has been vascularization, and we hope that this technology may help to address the problem."