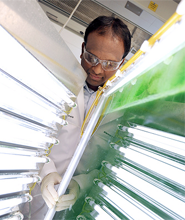

Now Hyun Woo Kim and Raveender Vannela, researchers at the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University are perfecting the means to culture these microbes—a potentially rich source of biofuels and biomaterials—in significantly greater abundance.

The work provides a vital foundation for optimizing a device known as a photobioreactor (PBR), in which these energy-packed photosynthetic organisms proliferate.

While a variety of candidates have been called into service for producing clean forms of energy to replace harmful fossil fuels—from corn ethanol to switch grass or various forms of algae—cyanobacteria offer a particularly attractive option. As Kim explains, “cyanobacteria are much easier to re-engineer because we have a lot of knowledge about them. We can control their growth so that we can produce large amounts of biofuel or biomaterial.” (The team works at Biodesign’s Center for Environmental Biotechnology, under director Bruce Rittmann.)

Now Hyun Woo Kim and Raveender Vannela are perfecting the means to culture these microbes—a potentially rich source of biofuels and biomaterials—in significantly greater abundance.

Now Hyun Woo Kim and Raveender Vannela are perfecting the means to culture these microbes—a potentially rich source of biofuels and biomaterials—in significantly greater abundance.

The new research indicates that the optimization of cyanobacterial growth requires a delicate interplay of CO2, phosphorus and sufficient light irradiation, within the PBR vessel containing the microbial crop. The group’s foundational study provides quantitative tools for evaluating factors limiting production of cyanobacteria within PBRs—a critical step along the path to large scale biofuel production. Results appeared recently in the journal Biotechnology and Bioengineering.

Photosynthetic cyanobacteria are able to produce roughly 100 times the amount of clean fuel per acre compared with other biofuel crops, and because their survival needs are simple—sunlight, water, CO2 and a few nutrients—they do not require arable land to be taken out of food production. Rather, cyanobacteria can be grown in rooftop PBRs or wherever sufficient quantities of sunlight and CO2 can be provided.

As Vannela notes, “the PBR uses solar photons as an energy source to convert CO2 to reduced forms such as biomass, proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates. It's a biological reactor, fixing solar energy into very useful forms of energy for human society.”

Cyanobacteria reproduce prolifically, achieving a high biomass yield and they are tolerant of a wide range of temperatures, salinities and pH conditions. In addition to biofuels, which are extracted from fat-containing lipids in the cyanobacteria, the microbes can also produce many chemically based materials useful for industrial applications, like biopolymers or isoprenes. Photosynthetic microbes are also valuable for the growing field of neutraceuticals, permitting the manufacture of anti-cancer agents from fatty acids or antioxidants like beta carotene.

For the current study, the group used wild type Synechocystis PC6803, cultured in a benchtop PBR, and supplied with the customary growth medium, known as BG-11. A series of semi-continuous experiments were conducted, in which three principle variables were manipulated and the resulting growth of cyanobacteria, observed. These were C02, light irradiance and phosphorus.

“In this study,” Kim notes, “we found that phosphorus is really important.” Indeed, the cyanobacteria were unable to make efficient use of carbon dioxide in their growth cycle until the BG-11 medium was supplemented with phosphorus. Augmenting the medium with additional phosphorus allowed higher biomass productivity in the bioreactor. Once the phosphorus limitation was overcome, light irradiance and CO2 became the limiting factors for growth.

While phosphorus content had been studied in the past with respect to the problem of eutrophication in lakes and other inland waters, its significance for controlled growth of phototrophs like cyanobacteria within a PBR had not been examined in detail. In a series of experiments, the team simulated the natural pattern of light irradiance produced by sunlight, while carefully controlling the levels of CO2 (applied at 2.5, 5.0 and 7.5 percent) and phosphorus.

Results showed that when all essential nutrients are supplied, light irradiance becomes the limiting factor, as the crowding of biomass within the containment vessel increasingly blocks available light to the cyanobacteria. This condition is overcome through periodic harvesting of biomass from the reactor. The advance of the team’s research was in quantifying these factors, in order to obtain optimal values for nutrients, CO2 and light irradiance.

Vannela and Kim stress that while they supplied CO2 and nutrients including phosphorus to the PBR’s cyanobacteria in their experimental design, ultimately, the nutrient source could come from waste streams or be recycled from the harvested biomass, while the excess CO2 produced by power plants could fulfill the microbe’s respiratory requirements. Thus, a closed loop could be formed, generating useful energy from water contaminants and the CO2 currently contributing to greenhouse warming.

The work performed by the group is one component in a large, multidisciplinary effort to make eventual commercial-scale production of biofuels and biomaterials a reality. Such research seeks to address one of the most significant societal challenges—finding a carbon-neutral replacement for destructive (and dwindling) fossil fuels.