Researchers from the Vanderbilt University and the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society have developed a new method to track the ultrafast phase changes that occur within solid materials like vanadium dioxide at intervals of below a trillionth of a second.

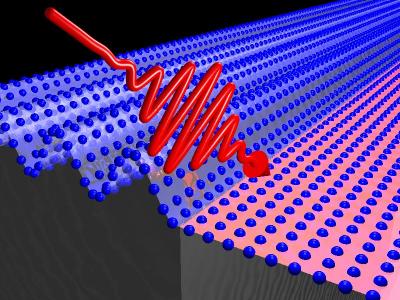

A femtosecond pulse of infrared laser light "pumps" the atomic lattice in vanadium dioxide, inducing a phase transition. Credit: Courtesy of Fritz Haber Institute

A femtosecond pulse of infrared laser light "pumps" the atomic lattice in vanadium dioxide, inducing a phase transition. Credit: Courtesy of Fritz Haber Institute

Dissolving sugar in water and melting of candle wax are few phase transitions that are common. These transitions produce significant changes in the physical properties of a material and they play a key role in nature as well as in industrial processes that range from steel production to chip fabrication. Vanadium dioxide (VO2) is one of the strange phase-change solid materials, which undergoes fastest transition from a semiconducting, transparent phase to a reflective phase. As the transition is too fast, scientists have difficulty in tracking them. To overcome this difficulty, Vanderbilt team has developed the new technique to get a complete picture of the phase changes in VO2.

The phase changes in VO2 can be produced either by hitting the material with a laser light pulse or by heating it above 150°C. The phase-change material, when mixed with specific additives, produces a window coating that has potential to prevent infrared transmission during hot periods and minimize heat loss on cool days. VO2 also has potential applications in cameras, sensors and optical shutters.

The method enables the scientist to observe several details, including the rearrangement of the electrons in the solid material and the movement of the huge atoms as the material changes from semiconducting to metallic phase. These details can help in the development of high-speed optical switches using the VO2 material.