Feb 6 2014

A group of Washington State University researchers have developed a chewing gum-like battery material that could dramatically improve the safety of lithium ion batteries.

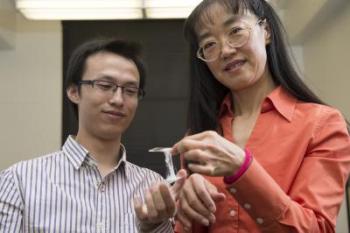

Washington State University graduate student Yu "Will" Wang (l) and Professor Katie Zhong have worked on an electrolyte that is twice as sticky as chewing gum. Credit: Washington State University

Washington State University graduate student Yu "Will" Wang (l) and Professor Katie Zhong have worked on an electrolyte that is twice as sticky as chewing gum. Credit: Washington State University

Led by Katie Zhong, Westinghouse Distinguished Professor in the School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, the researchers recently reported on their work in the journal, Advanced Energy Materials. They have also filed a patent.

High performance lithium batteries are popular in everything from computers to airplanes because they are able to store a large amount of energy compared to other batteries. Their biggest potential risk, however, comes from the electrolyte in the battery, which is made of either a liquid or gel in all commercially available rechargeable lithium batteries. Electrolytes are the part of the battery that allow for the movement of ions between the anode and the cathode to create electricity. The liquid acid solutions can leak and even create a fire or chemical burn hazard.

While commercial battery makers have ways to address these safety concerns, such as adding temperature sensors or flame retardant additives, they "can't solve the safety problem fundamentally,'' says Zhong.

Zhong's research group has developed a gum-like lithium battery electrolyte, which works as well as liquid electrolytes at conducting electricity but which doesn't create a fire hazard.

Researchers have been toying around with solid electrolytes to address safety concerns, but they don't conduct electricity well and it's difficult to connect them physically to the anode and cathode. Zhong was looking for a material that would work as well as liquid and could stay attached to the anode and cathode – "like when you get chewing gum on your shoe,'' she told her students.

Advised by Zhong, graduate student Yu "Will" Wang designed his electrolyte model specifically with gum in mind. It is twice as sticky as real gum and adheres very well to the other battery components.

The material, which is a hybrid of liquid and solid, contains liquid electrolyte material that is hanging on solid particles of wax or a similar material. Current can easily travel through the liquid parts of the electrolyte, but the solid particles act as a protective mechanism. If the material gets too hot, the solid melts and easily stops the electric conduction, preventing any fire hazard. The electrolyte material is also flexible and lightweight, which could be useful in future flexible electronics. You can stretch, smash, and twist it, and it continues to conduct electricity nearly as well as liquid electrolytes. Furthermore, the gummy electrolyte should be easy to assemble into current battery designs, says Zhong.

While the researchers have shown good conductivity with their electrolyte, they hope to begin testing their idea soon in real batteries. Zhong's group was part of a group of WSU researchers that received support from the Washington Research Foundation last year to equip a battery manufacturing laboratory for building and testing lithium battery materials in commercial sizes. The research groups also are working together to combine their technologies into safer, flexible low-cost batteries.