Feb 18 2016

The promise of high conversion efficiency with lower cost has put perovskite solar cells under intense research in the field of photovoltaics.

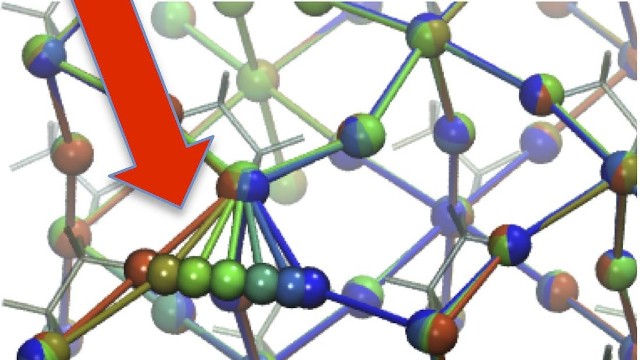

Stroboscopic image of the halide ions migration path in perovskites. The color of atoms and bonds corresponds to the time along the migration path. Halide ion migration in perovskites is a relatively fast process as it requires minimal distortion of the rest of the lattice, and henceforth little energy. Credit: Simone Meloni | credits: Nature Communications/NPG

Stroboscopic image of the halide ions migration path in perovskites. The color of atoms and bonds corresponds to the time along the migration path. Halide ion migration in perovskites is a relatively fast process as it requires minimal distortion of the rest of the lattice, and henceforth little energy. Credit: Simone Meloni | credits: Nature Communications/NPG

However, a frequent problem that limits the determination of their efficiency is the so-called hysteresis in their current-voltage curves, which makes it difficult to accurately determine the real photoconversion efficiency of a given perovskite solar cell. EPFL scientists have now determined what lies at the heart of hysteresis by combining experimental and computational approaches. The study is published in Nature Communications.

Hysteresis refers to a time-dependent loss of output in a given system, and can limit the determination of the system’s real efficiency. How hysteresis arises in perovskite solar cells is hotly debated in the community today, with different studies proposing ferroelectricity, trapping and detrapping of charge-carriers or ion movement (e.g. rotation) inside the absorber material. Ultimately, understanding the origin of hysteresis can help develop ways to reduce it and improve the overall efficiency of this solar cell.

A team of EPFL researchers from the labs of Michael Grätzel, Ursula Röthlisberger, and Mohammad Nazeeruddin investigated the molecular origin of hysteresis by combining an experimental with a computational approach. The experimental part involved temperature-dependent measurements of the current-voltage curves using an Arrhenius-type analysis, which describes how reaction rates depend on temperature.

This allowed the scientists to determine the activation energy for the process behind hysteresis – that is, the minimum energy needed to trigger hysteresis in a perovskite material. The materials used here were methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) and bromide (MAPbBr3). The measurements showed that bromide-based photovoltaic devices generally have lower activation energies than iodide-based ones.

In the computational part of the study, the scientists used first-principles simulations. These showed that the timescale for the rotation of the MA+ inorganic cation cannot be the origin of hysteresis, as this takes place in a picosecond range – too fast for hysteresis, which happens over a timeframe several orders of magnitude longer.

On the other hand, the computational study did reveal that the activation energies for the migration of the halide ions match the values determined by the experimental part of the study. This suggests that it is the migration of this species that causes the hysteresis observed in perovskite solar cells.