May 8 2019

The apparent downside of solar panels is that they require sunlight to produce electricity. Some have perceived that for a device on Earth facing space, which has a very cold temperature, the chilling outflow of energy from the device can be collected using the same kind of optoelectronic physics that has been used to harness solar energy. New research, in the latest issue of Applied Physics Letters, from AIP Publishing, aims to offer a possible path to producing electricity like solar cells but that can drive electronics at night.

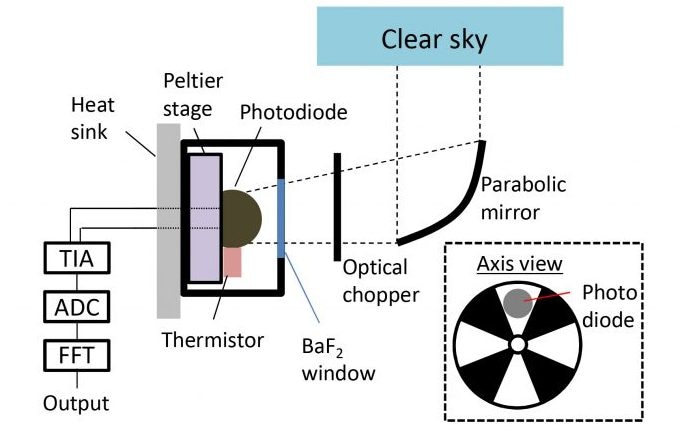

Schematic of the experimental infrared photodiode that has generated electricity directly from the coldness of space. (Image Credit: Masashi Ono)

Schematic of the experimental infrared photodiode that has generated electricity directly from the coldness of space. (Image Credit: Masashi Ono)

An international team of researchers have shown for the first time that it is feasible to produce a measurable amount of electricity in a diode straight from the coldness of the universe. The infrared semiconductor device is positioned to face the sky and uses the temperature variance between Earth and space to create the electricity.

The vastness of the universe is a thermodynamic resource. In terms of optoelectronic physics, there is really this very beautiful symmetry between harvesting incoming radiation and harvesting outgoing radiation.

Shanhui Fan, Author of Study Paper

Contrary to leveraging incoming energy as a typical solar cell would, the negative illumination effect permits electrical energy to be reaped as heat leaves a surface. Present-day technology, though, does not trap energy over these negative temperature variances as efficiently.

By positioning their device toward space, whose temperature is close to mere degrees from absolute zero, the team was able to discover a substantial enough temperature difference to produce power through an early design.

“The amount of power that we can generate with this experiment, at the moment, is far below what the theoretical limit is,” said Masashi Ono, the paper’s other author.

The team learned that their negative illumination diode produced about 64 nanowatts per square meter, a minute amount of electricity, but a crucial proof of concept, that the authors can enhance on by refining the quantum optoelectronic properties of the materials they use.

Calculations carried out after the diode produced electricity revealed that, when atmospheric effects are taken into account, the present device can theoretically yield nearly 4 W/m2, approximately one million times what the team’s device produced and sufficient to help work machinery that is needed to function at night.

By comparison, present-day solar panels produce 100 to 200 W/m2.

While the results exhibit potential for ground-based devices facing the sky, Fan said the same principle could be applied to get back waste heat from machines. For the moment, he and his team are concentrating on enhancing the performance of their device.