Refrigeration methods have significantly impacted various industries, revolutionizing everything from food preservation techniques in the home and industry to providing a safe chilled environment for storing samples, reagents, blood, plasma, enzymes, cell cultures, and patient medication in the laboratory.

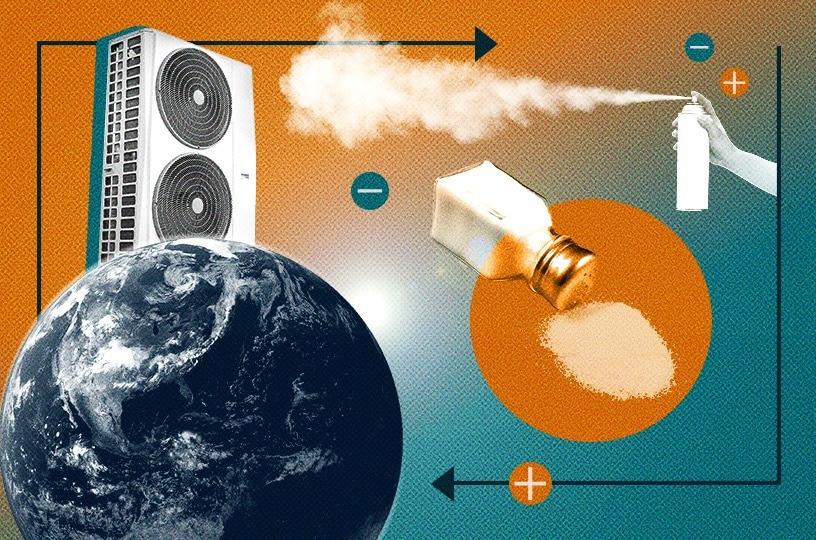

Image Credit: Jenny Nuss/Berkeley Lab

Yet, conventional refrigeration techniques use gaseous mixtures and consume high levels of energy that can pose a risk to the environment, contributing to global warming.

Recently, Drew Lilley and Ravi Prasher, researchers at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), have developed a new carbon-negative method inspired by the salting and gritting of roads to limit ice formation in the winter months.

Ionocaloric Cooling

The new carbon-negative method that Lilley and Prasher have dubbed ‘ionocaloric cooling’ controls the melting and crystallization of material via the application of a solution containing ions that generate the ionocaloric cycle.

The pair have been inspired by the challenge to develop high-efficiency cooling using safe, low–global warming potential refrigerants for combatting the climate crisis.

The landscape of refrigerants is an unsolved problem: No one has successfully developed an alternative solution that makes stuff cold, works efficiently, is safe, and doesn’t hurt the environment.

Drew Lilley, Graduate Research Assistant, Berkeley Lab

“We think the ionocaloric cycle has the potential to meet all those goals if realized appropriately,” he added.

Climate Goals

With global climate goals high on the agenda and consistently in the headlines, policymakers and world leaders are under pressure to respectfully meet climate goals by 2030 and 2050. One of the goals listed comes under the Kigali Amendment, which was made in October 2022 and widely accepted by 145 parties, including the US.

The agreement made under the Kigali Amendment is aimed at reducing the production and consequent consumption of HFCs (hydrofluorocarbons) by a minimum criteria of 80% over the next 25 years. HFCs are known greenhouse gases that, while considered safer than CFCs, possess a considerable heat-trapping effect thousands of times greater than CO2.

The carbon-negative ionocaloric cooling method developed by Lilley and Prasher could help speed up the transition from using HFCs in refrigeration techniques to more environmentally compatible refrigeration methods.

Ionocaloric cooling sits alongside other caloric cooling methods, which employ magnetism, pressure, stretching, and electric fields to control the state of solid materials to either absorb or release heat.

Method Potential

Ionocaloric cooling differs from other caloric methods by using ions to trigger solid-to-liquid phase changes. Incorporating a solution rather than sole manipulation of solid materials means that the transitional materials can be pumped through a system, making them easier and more effective at transporting heat.

Moreover, the potential of this new carbon-negative ionocaloric cooling method could theoretically compete with and even surpass the efficiency of conventional gaseous refrigerants, including HFCs.

This method’s potential is outlined in Lilley and Prasher’s paper published in the journal Science. Here, the authors also discuss and demonstrate how the technique has been applied experimentally in the laboratory.

There’s potential to have refrigerants that are not just GWP [global warming potential]-zero, but GWP-negative.

Drew Lilley, Graduate Research Assistant, Berkeley Lab

The researchers used an iodine and sodium-based salt in combination with ethylene carbonate – a solvent used in lithium-ion batteries – to test their theory.

Using a material like ethylene carbonate could actually be carbon-negative, because you produce it by using carbon dioxide as an input. This could give us a place to use CO2 from carbon capture.

Drew Lilley, Graduate Research Assistant, Berkeley Lab

By introducing a current to the solution, the ions rearrange, which alters the melting point of a material. Upon melting, the material forms a solution that can absorb heat from its surroundings. By removing the ions, the solution moves back into a solid state to release heat.

“We have this brand-new thermodynamic cycle and framework that brings together elements from different fields, and we’ve shown that it can work,” Prasher said. “Now, it’s time for experimentation to test different combinations of materials and techniques to meet the engineering challenges.”

Lilley and Prasher have acquired a provisional status for their patent of the ionocaloric cooling method for refrigeration and are now licensing the technology. The potential is not only innovation in carbon-negative refrigeration methods but could also have a real positive impact on current climate goals in the future.

References and Further Reading

Biron, L. (2023) Berkeley lab scientists develop a cool new method of refrigeration, News Center. Available at: https://newscenter.lbl.gov/2023/01/03/cool-new-method-of-refrigeration/

Lilley, D. and Prasher, R. (2022) “Ionocaloric refrigeration cycle,” Science, 378(6626), pp. 1344–1348. Available at: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.ade1696.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.