In the realm of advanced manufacturing, 3D printing has emerged as a major technology, offering unprecedented flexibility in prototyping. Boston Micro Fabrication’s latest white paper delves into the nuances of micro and nano 3D printing, addressing a fundamental question: what level of resolution is truly indispensable for practical applications?

Image Credit: Boston Micro Fabrication (BMF)

Advanced additive manufacturing techniques are now becoming a mainstay of many industries. Of these methods, 3D printing has been particularly successful and is now being used to print a variety of materials, from nanomedicines to foods.1,2

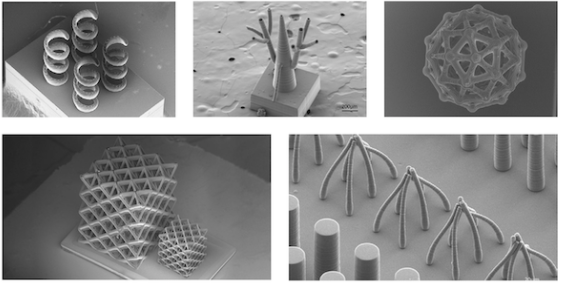

The popularity of 3D printing stems from its remarkable versatility as a prototyping technique. With 3D printing, it becomes feasible to fabricate intricate structures and shapes that are unattainable through conventional manufacturing methods.

Advancements in positioning motor precision and the development of innovative printing materials have also significantly enhanced the quality and resolution achievable with 3D printers. Nevertheless, the question remains: is printing at the nanometer scale truly practical, and is it essential for the majority of applications?

A nanometer is 1 x 10-9 m, and the smallest viruses are only on the scale of ~ 20 nm in diameter. A micrometer is 1 x 10-6 m, making it a thousand times larger than a nanometer.

Unfortunately, the terms nanoscale and microscale are often used interchangeably in science and engineering. Currently, the state-of-the-art in 3D printing resolution with specialist techniques is on the order of hundreds of nanometers.3 While nanoscale objects are often defined as being on a similar size scale to this, for many applications, even micrometer resolution is more than sufficient.

While printing objects that are hundreds of nanometers in scale may now be possible, printing at very small length scales introduces a number of complications and expenses into the printing process.

Many customers need accuracy and quality in advanced manufacturing rather than the ultimate printing resolution. Thus, having a smooth and uniform printed surface is often much more important. However, extra demand is placed on all parts of the 3D printer when printing at very small scales—the motors and actuators need to be highly precise and sensitive; therefore, greater control is needed for the laser beam, and the material properties need to be more controllable.

This article explores micro and nano 3D printing, dissecting its practicalities and complexities, and provides scientific insights into the delicate balance between technological capabilities and real-world application.

Download White Paper to Learn More

Download White Paper to Learn More

References and Further Reading

- Bhat, Zuhaib F. et al. 2021. “3D Printing: Development of Animal Products and Special Foods.” Trends in Food Science and Technology 118(PA): 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.09.020.

- Jain, Keerti et al. 2021. “3D Printing in Development of Nanomedicines.” Nanomaterials 11(2): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.09.020

- Li, Qi et al. 2022. “Mechanical Nanolattices Printed Using Nanocluster-Based Photoresists.” Science 378(6621): 768–73.

This information has been sourced, reviewed and adapted from materials provided by Boston Micro Fabrication (BMF).

For more information on this source, please visit Boston Micro Fabrication (BMF).