Dec 11 2020

A new study led by Curtin University has demonstrated that the formation of bubbles on electrodes, which is often considered to be a hindrance, could be advantageous.

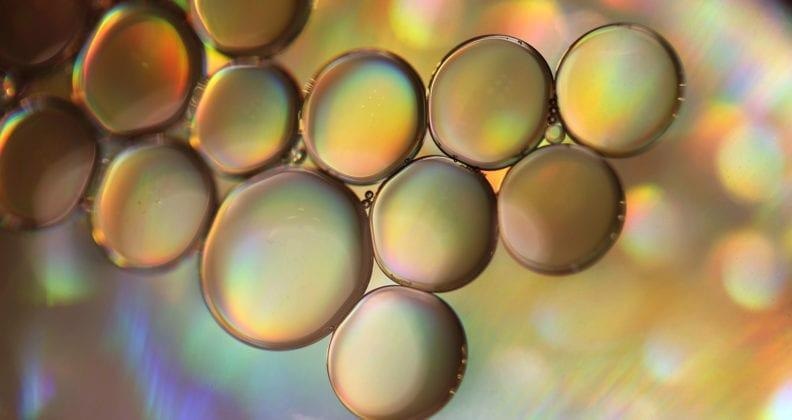

Image Credit: Curtin University.

This is because bubbles, or oil droplets, that are deliberately added can speed up processes such as the production of chlorine and the elimination of pollutants like hydrocarbons from contaminated water.

According to Dr Simone Ciampi from Curtin’s School of Molecular Life Sciences, several industrial processes are electrochemical, which implies that the preferred chemical reaction for producing an end product is supported by the flow of electrical currents.

Electrodes assist chemists to achieve required electrochemical reactions, such as in the purification of alumina, and the technology used to produce chlorine for swimming pools. Often over the course of their use, small bubbles of gas begin to form on these electrodes, blocking parts of their surface. These bubbles prevent fresh solution from reaching the electrodes, and therefore, slow down the necessary reactions.

Dr Simone Ciampi, School of Molecular Life Sciences, Curtin University

“It was generally thought these bubbles essentially stopped the electrode from working properly, and the appearance of the bubbles was a bad thing. However, our new research suggests otherwise,” added Dr Ciampi.

The researchers used electrochemistry, fluorescence microscopy and multi-scale modeling to demonstrate that in the proximity of bubbles that bind to an electrode surface, valuable chemical reactions take place under conditions where such reactions would generally be regarded impossible.

According to Dr Yan Vogel, study co-researcher also from Curtin’s School of Molecular and Life Sciences, it was the 'impossible' reactions in the corona of bubbles that triggered the team’s interest and warranted further analyses.

We revealed for the first time that the surrounding surface of an electrode bubble accumulates hydroxide anions, to surprisingly large concentrations. This population of negatively charged ions surrounding bubbles is unbalanced by ions of the opposite sign, which was quite unexpected. Usually charged chemical species in solution are generally balanced, so this finding showed us more about the chemical reactivity of bubbles.

Dr Yan Vogel, Study Co-Researcher, School of Molecular and Life Sciences, Curtin University

Vogel continued, “Basically we’ve learned that surface bubbles can actually speed up electrochemical reactions where small molecules are joined to form large networks of molecules in a polymer, like in camera films or display devices like glucose sensors for blood sugar monitoring.”

The research team under the guidance of Curtin University included Dr Nadim Darwish from Curtin’s School of Molecular Life Sciences and researchers from the Australian National University, the University of New South Wales and the University of Western Australia.

Journal Reference:

Vogel, Y. B., et al. (2020) The corona of a surface bubble promotes electrochemical reactions. Nature Communications. doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20186-0.