Protein aggregation may take place at any stage during the development of protein-based therapeutic compounds. Several light scattering methodologies have been developed for its characterization, enabling the determination of protein aggregate composition in therapeutic formulations through the application of orthogonal approaches.

Protein aggregation is a phenomenon that takes place during storage, manufacturing, administration, and shipping of a therapeutic protein product. As protein aggregates can considerably impact the efficacy, stability, and safety of the therapeutic agent, their sizes and abundance must be characterized at each step of the production process. Generally, the sizes of protein aggregates vary from a few nanometres to hundreds of micrometers.

Static and Dynamic Light Scattering Techniques

Light scattering (LS) techniques, both static light scattering (SLS) and dynamic (DLS) have been used for the characterization of protein aggregates from several nanometres (monomer/low-order oligomer) to micrometers (high-order aggregate and aggregate particles) in diameter. The intensity of the light scattering signal is proportional to both molar mass and concentration of the species in solution (or stable suspension).

Consequently, light scattering detectors are highly sensitive in detecting large aggregates, even in small quantities. Furthermore, modern SLS and DLS detectors can be coupled to online fractionation techniques such as size exclusion chromatography (SEC) and field flow fractionation (FFF), thus allowing excellent resolution and extensive characterization of the different sub-species present in protein formulations.

Even though both separate molecules are based on their hydrodynamic volume, SEC is typically used for protein separation; whereas, FFF can be used for both proteins and nanoparticles. SEC is common in most labs and has been utilized more widely than FFF to separate and quantify the stable protein isoforms from fragments and aggregates.

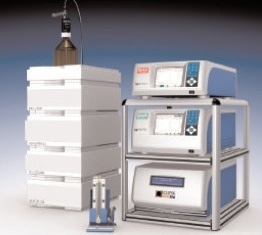

Static light scattering can include low angle (LALS), right angle (RALS), and multi-angle LS (MALS), and MALS is, by far, the most accurate, versatile, and widely utilized detector for polymer and biopolymer characterization. This is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The separation of protein monomers and aggregates is accomplished by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) or asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation (AF4). On-line analysis of molar mass and size utilizes multi-angle light scattering (MALS), dynamic light scattering (DLS), UV/Vis absorption (UV), and differential refractometry (dRI).

MALS detectors can be used in both batch mode and in combination with SEC or FFF separation. Importantly, the addition of a MALS detector to SEC or FFF provides absolute MW (i.e., independently of geometry, density, and Separation of protein monomers and aggregates is accomplished by size-exclusion chromatography [SEC] or asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation [AF4]).

On-line analysis of molar mass and size utilizes multi-angle light scattering (MALS), dynamic light scattering (DLS), UV/Vis absorption (UV), and differential refractometry (dRI), but also additional information such as stoichiometry of protein conjugates, root mean square radius (Rg, when greater than 10nm), or number density data for aggregate particles, among other parameters.

Determination of Aggregate Particle Structure

In order to measure protein radius less than 10nm or to determine the structure of aggregate particles, DLS can also be used with MALS, downstream of the SEC or FFF, to provide hydrodynamic radii (Rh) of the eluting species.

For proteins, combined information from MALS (MW) and DLS (Rh) can provide some insight into molecular conformation or folding states. For larger species, the ratio of the root means square radius and hydrodynamic radius (from MALS and DLS, respectively) can be used not only in the derivation of particle shape but also for the determination of mass distributions within the particle (e.g., differentiation between empty and filled nanoparticle cages).

To accurately determine the distribution of protein aggregates, MALS, or DLS measurement in batch mode without separation is often performed. The batch analysis is the primary application mode of DLS and can be used to monitor aggregation as a function of various parameters, such as concentration, buffer composition, temperature, and time. In contrast to MALS, no prior knowledge of concentration is required in DLS.

These factors along with the ability to make measurements in less than one minute underscore batch DLS as a useful tool for high-throughput screening of formulation stability especially using automated DLS instrumentation with well plates.

Although incredibly sensitive to the presence of minute amounts of aggregate, resolution of sub-species by batch DLS requires that their radii differ by at least a factor of four. The evolution of low-order oligomers can only be monitored using an alternative metric (e.g. polydispersity index) as a proxy. This is not a limitation, of course, with online DLS following fractionation.

As with DLS, batch MALS measures average MW with limited resolution of different species in a sample. By comparison, however, MALS is far more sensitive than DLS for assessing lot-to-lot variability. Under optimal conditions, batch MALS can readily sense a 1% change in average MW arising from a minor difference in either the type or amount of aggregates in solution. When measured at different concentrations, batch MALS data can be used to characterize reversible self-association of a protein, resolve and quantify different oligomers present in a sample over a wide concentration range.

Conclusion

In summary, two basic types of light scattering detection, static and dynamic, are typically employed for the characterization of physical properties in the development of biotherapeutic formulations. Both types can be used for either batch analysis or for improved detection/characterization in conjunction with various fractionation techniques.

Light scattering following fractionation (by SEC or FFF) enables characterization and resolution of different aggregates in a protein solution that is irreversibly associated; however, the separation process itself can sometimes alter the aggregation state and/or content in the sample.

Such perturbations do not take place during batch measurements. In contrast, although the resolution of different species is limited, batch analyses are a powerful means for high-throughput screening for solution conditions that promote protein aggregation, as well as for characterizing various specific and non-specific associations. Any of these orthogonal yet complementary approaches independently provides useful information and, when employed together, they comprise a robust toolkit for comprehensive characterization of aggregation phenomena in protein formulations.

References and Further Reading

- Reprinted with permission from "Methodologies for characterizing protein aggregation" by Michelle Chen, 2013. Sp2 InterActive,November/December 2013, pg. 20-22.

This information has been sourced, reviewed and adapted from materials provided by Wyatt Technology.

For more information on this source, please visit Wyatt Technology.