Apr 18 2013

To American inventors, the “home garage” has always been a symbol of possibility—a place for tinkerers to create and innovate. More than a century ago, the Wright brothers founded a cycle sales and repair business from a modest storefront and soon after invented a bike hub that was self-oiling. Everyone knows what they did next in the field of aviation.

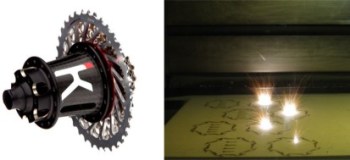

The Kappius rear hub (left) is a groundbreaking, lightweight, durable, oversized design. The components are manufactured by Harbec, using direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) from EOS, (right) from an extremely durable "tool steel." (Courtesy Kappius Components and Harbec)

The Kappius rear hub (left) is a groundbreaking, lightweight, durable, oversized design. The components are manufactured by Harbec, using direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) from EOS, (right) from an extremely durable "tool steel." (Courtesy Kappius Components and Harbec)

Harley Davidson’s motorized bikes were born in a backyard shed. HP’s Hewlett and Packard and Apple’s Jobs and Wozniak helped define the modern computer age from their suburban startup shops. And garage-based entrepreneurs are still at it in the 21st century.

About four years ago, Russ Kappius—mountain-bike enthusiast, winner of six Masters racing titles, and a research geophysicist/software developer—became obsessed with bicycle hubs. He wanted more speed and responsiveness, but wasn’t sure how to get it.

His ‘Aha!’ moment came when a demo part from one of the bicycle industry’s major suppliers arrived in the mail. “When I saw it, I got an idea for a new hub-drive system,” says Kappius. “I did a patent search and quickly learned that there wasn’t anything out there that covered what I was thinking.”

After working out a design for a novel oversized hub and high-performance drive assembly that would transfer more power from pedal to chain to wheel, Kappius patented the concept and began looking for a way to fabricate the parts.

One barrier to entrepreneurial success in any age is finding an efficient, cost-effective and fast route from product idea to physical product. At first, Kappius and his son, Brady (an engineer and pro mountain-biker), made do with machining methods to fabricate their hub, then field-testing and tweaking the design. “Because we’re a startup, we quickly learned that we needed to make design changes and get new parts to our customers fast to stay competitive,” the elder Kappius says.

Then in late 2011, Kappius discovered direct metal laser sintering (DMLS™), an industrial additive manufacturing (“3D printing”) technology from German-based EOS GmbH that met their rapid turnaround needs and enabled them to produce parts to exacting specifications and with additional design complexity. He also located Harbec—a New York-based DMLS provider—and sent them a CAD file that included the latest design refinements.

In the first week of field testing the latest hub assembly, the elder Kappius won a race. “We went from concept to bike-ready components in about a month,” he says. “I’ve never been able to move that quickly before.”

Kappius Components’ hubs have been through a half-dozen design iterations since the “garage doors” opened for business in 2008. But the recent move to laser sintering has accelerated the speed of improvements. “As a software engineer, I am able to change anything at any time to make the code better,” says Kappius. “With DMLS, I have similar flexibility. It allows me to make small design changes and almost immediately test them on the bike. That’s the beauty of the technology.”

The beauty of the lightweight-yet-durable hub, on the other hand, comes from the sleek carbon-fiber shell (handmade by the younger Kappius), as well as the drive assembly housed inside it—including a drive ring, toothed inner ring, and pawls (or flippers), all made using DMLS.

The technological advance in the system comes from two developments: the oversized design—it’s about twice the current standard diameter—and many more points of engagement than standard designs. These two features constitute the heart of the hub’s intellectual property and allow a cyclist to translate the act of pedaling into increased drive force.

When he first geared up for business, Kappius bought ready-made pawls and engineered the rest of his system around them. Once he discovered laser sintering, however, he was able to redesign the pawl itself and add a one-millimeter cylindrical basal extension, which positioned them better when they engaged.

Laser sintering’s advantage over other fabrication methods is the ease with which it can manufacture cylindrical and other irregularly shaped parts, like Kappius’ pawls. Since it’s an additive rather than subtractive process, the technology “grows” parts layer by layer using powdered materials (metals, polymers, and foundry sands) that are heated and melted by a laser. The beam follows the outlines and contours of a series of cross-sectional slices taken from a 3D digital model.

Kappius is pleased with the results. “The tool steel is super strong,” he says. “I haven’t had a single hub failure. Even the big manufacturers can’t say that.” Bicycling magazine included Kappius hubs on the timeline of noteworthy bicycle innovations in their 50th anniversary issue in November, 2011.

DMLS technology is helping level the field between Kappius’ two-person company and the bigger players in the bicycle industry. With fabricator Harbec supplying parts on an as-needed basis, the father-son team assembles components in their home shop after hours and ships them out to early-adopter cyclists around the world. Production is accelerating fast for the young company—they sold about 100 hub assemblies this past year and are projecting sales of 500 in 2014.

The benefits of DMLS for the bike-hub creator? “Number one is design freedom,” says Kappius. “Number two is the material strength. Three is lead time.”

And then there’s also the rider experience. “People just love the hub,” says Kappius. “They’re faster and fun to ride.”