Image Credit: Padture lab | Brown University

Image Credit: Padture lab | Brown University

Image Credit: Padture lab | Brown University

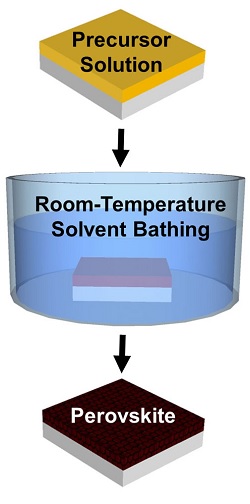

This new method involves using a solvent bath at room-temperature in order to generate perovskite crystals instead of using a blast of heat as in other conventional crystallization techniques.

The method produces high-quality crystalline films with the accurate control of thickness over large areas. It also paves the way for the mass production of perovskite cells.

Perovskites are a class of crystalline materials that act as excellent light absorbers. These are more inexpensive to manufacture when compared to the silicon wafers used in standard solar cells.

Perovskite cells were first produced in 2009 with an efficiency of around 4%. However, the efficiency was improved at an astounding pace over the years to more than 20%.

Due to this rapid development in the performance of perovskite cells, researchers have started to commercialise the product.

Almost all methods used to manufacture the films require heat. Perovskite precursor chemicals are dissolved in a solution and coated onto a substrate. The solvent is removed with the application of heat, allowing the perovskite crystals to form as a film over the substrate.

The crystals tend to form unevenly upon heating, leaving behind tiny pinholes in the film. These pinholes reduce the efficiency of solar cells.

In addition, the application of heat can also restrict the deposition of films on the substrate. Flexible plastic substrates, however, cannot be employed owing to their ability to break at elevated temperatures.

People have made good films over relatively small areas — a fraction of a centimeter or so square. But they’ve had to go to temperatures from 100 to 150 degrees Celsius, and that heating process causes a number of problems.

Nitin Padture, Professor of Engineering and Director of the Institute for Molecular and Nanoscale Innovation

With an aim to determine the method for manufacturing perovskite crystal thin films without heat application, Yuanyuan Zhou, a graduate student in Padture’s lab came up with a solvent-solvent extraction (SSE) approach.

In the SSE method, perovskite precursors were dissolved in NMP solvent and coated on a substrate. The substrate was then bathed in diethyl ether (DEE) which removes the NMP solvent, leaving behind an ultra-smooth perovskite crystal film.

As this method does not involve heating, the crystals are virtually formed on any substrate including heat-sensitive polymer substrates used in flexible photovoltaic. In addition, the complete SSE crystallization process can be performed within two minutes, unlike other heat-treatment methods that takes one hour or more.

The SSE method produces very thin films and maintains high quality. In general, standard perovskite films are around 300nm thick. However, Zhou could make high quality films that are as thin as 20nm. The SSE films can also be thickened without creating pinholes.

Using the other methods, when the thickness gets below 100 nanometers you can hardly make full coverage of film. You can make a film, but you get lots of pinholes.

In our process, you can form the film evenly down to 20 nanometers because the crystallization at room temperature is much more balanced and occurs immediately over the whole film upon bathing.

Nitin Padture, Professor of Engineering and Director of the Institute for Molecular and Nanoscale Innovation

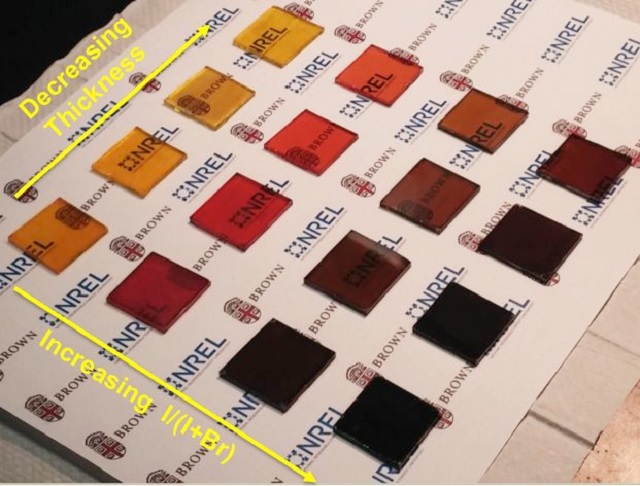

These ultra-thin films are partially transparent, enabling applications in photovoltaic windows. In addition, Zhou said that the films can be made in different colours by varying the composition of perovskite precursor solution.

“These could potentially be used for decorative, building-integrated windows that can make power,” Padture said.

The team further plans to carry out the process refinement using their early results. The initial testing of SSE film cells carried out in the presence of scientists from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Colorado showed a conversion efficiency of more than 15%.

Solar cells made using 80nm semitransparent films via SSE approach were observed to have higher efficiency when compared to any other ultra-thin film.

“We think this could be a significant step toward a variety of commercially available perovskite cell products,” Padture said.

This research has been published in the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Journal of Materials Chemistry A.