Apr 21 2004

Researchers at Purdue University have developed the first system capable of searching a company's huge database of three-dimensional parts created with computer-aided design software.

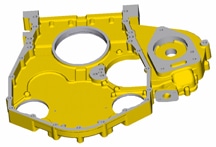

CAD generated part

|

Such "parts search engines" could save time and millions of dollars annually by making it easier for companies to "reuse" previous designs, benefiting from the lessons learned in creating past parts.

"Designers spend about 60 percent of their time searching for the right information, which is rated as the most frustrating of engineers' activities," said Karthik Ramani, a professor of mechanical engineering and director of the Purdue Research and Education Center for Information Systems in Engineering. "The whole power of computers is lost if you are not able to retrieve and 'reuse' what you have created in the past."

The new system enables people to select an inventoried part that resembles the desired part and retrieve a "cluster" of like items. Users also can sketch the desired part entirely from memory, or they can choose a part that looks similar from the company's catalog and then sketch modifications to that part. The system then assists in finding the desired part.

Details about the new parts search system were described in several research papers presented this month in Lausanne, Switzerland, during the Fifth International Symposium on Tools and Methods of Competitive Engineering.

Even though computer-aided design, or CAD, parts can easily be stored in a database because they are originally created in a computer, there is no commercially available search system for finding a specific part based on its three-dimensional shape.

"The true potential power of computers is not unleashed if you just use them to manage data but not search for data," Ramani said.

CAD systems were introduced a few decades ago for such daunting projects as creating better ship hulls and airplane wings. But the systems are now routinely used to design everything from automotive water pumps to industrial machine parts.

"One of the great disappointments of CAD has been the difficulty of reusing data," Ramani said. "Once CAD information has been created and used, it is often stored and forgotten. As a result, industry loses a lot of money by not being able to reuse earlier parts. The proverbial wheel is reinvented many times."

CAD generated part

|

The international conference is sponsored by Ecole Polytechnique Federale Lausanne and Delft University of Technology. One of the research papers presented focused on a procedure for converting the complex three-dimensional CAD part into a simplified "skeletal graph" capable of being searched by a computer. That paper was written by Ramani, graduate students Kuiyang Lou, Subramaniam Jayanti, Natraj Iyer and Yagnanarayanan Kalyanaraman, and Sunil Prabhakar, an assistant professor of computer science.

"We take a 3-D model of a part and convert it into a bunch of small cubes called voxels, which stands for volume elements," Ramani said.

The system uses complex software algorithms to convert the voxels into the skeletal graph, which is based on "feature vectors," or numbers that represent a part's shape.

"Like our skeleton, it represents the bare bones of a part's shape and features, such as how many holes it contains and where the holes are located," Ramani said.

The system creates searchable versions of shapes in three categories: solid, hollow or a combination of both.

"For example, a coffee cup is hollow, like a shell, but its handle might be solid, so the cup combines both types of shapes, which have to be represented differently for them to be searchable," Ramani said. "The idea here is being able to reduce it into a skeletal graph that is hierarchical."

By hierarchical, Ramani means the simplified skeletal graph contains links to more complex graphs and data. Once the skeletal graph is retrieved, those other more complex designs and data can be accessed.

Not only will the system enable employees to find parts, but it will provide access to valuable background about how the part was produced, including details about machining and casting, which, in turn, provides information about how much it costs to make the part.

"Corporate memory is short," Ramani said. "People leave, managers come and go. They forget file names and project names. This type of system allows you to retrieve your own company's knowledge, your own company's history.

"Let's say there are 1.3 million parts in your inventory. If you are trying to design a part and you can find something similar that was produced in the past that has a lot of value."

Design engineers spend about six weeks per year looking for information on parts, he said.

"The shape-search system will allow engineers to cut this time down by as much as 80 percent," Ramani said.

A series of experiments in which people used the system to find parts showed that it has an accuracy of up to 85 percent.

"We allow a person to tell the system which retrieved parts are the closest matches," Ramani said. "And as a result of that feedback, which we call relevance feedback, the system begins to understand a little bit more about what you are looking for and it starts focusing on that."

The system also allows the user to fine-tune the search to specify aspects such as whether a part was created by casting or machining.

"So the search takes place through multiple representations of the part in a multistep process, which is very important," Ramani said. "This is not a simple, single-step approach that others have tried."

Relevance feedback requires algorithms that use "neural networks," or software that mimics how the human brain thinks.

"What you want to do is bridge the gap between what's in your head – your idea of what the part looks like – and what's in this huge inventory of parts," Ramani said. "That is not a trivial problem."

Experiments showed that such multistep searches are an average of 51 percent more accurate than a single-step search.

The system is not quite ready for commercialization.

"We have solved significant problems, but there are remaining challenges," Ramani said.

The engineers are working with Zygmunt Pizlo, an associate professor of psychological sciences at Purdue, to help improve the system by incorporating information about human perception.

"Working with a psychology expert will help us design experiments aimed at bridging the gap between the human being and the system," Ramani said. "We are putting a lot of effort into improving the human interface."

The work has been funded by the Indiana 21st Century Research and Technology Fund, created by the state to promote high-tech research and development and to help commercialize innovations.

A patent has been filed, and a private company, Imaginestics LLC, located in the Purdue Research Park, has agreed to license the technology.