Nov 14 2008

A team of scientists at the University of Leeds in the UK has invented a biosensor device that can identify disease using nanotechnology. The device, which may revolutionise the science of diagnosis, uses antibodies to detect biomarkers, molecules in the body used to identify disease. The aim of the ambitious ELISHA project, backed by the EU with EUR 2.7 million in funding, is to reduce diagnosis time to 15 minutes. The new invention may be on sale in just three years.

There are many shortcomings to the current method of disease diagnosis, which was developed in the 1970s and is based on analysis of blood and urine samples. The tests have to be carried out in a pathology lab by highly trained staff, they take about two hours and are expensive. A simpler technique, which would allow swifter diagnosis at less expense and in more a more convenient location such a doctor's surgery, would be less intimidating for patients and more cost effective for hospitals and health services.

Enter ELISHA ('Electronic immuno-interfaces and surface nanobiotechnology: a heteroxical approach') and its brand new biosensor diagnosis device. A team of nine partners from five EU countries including universities, research institutes and SMEs developed a device that will make diagnosis both less expensive and more flexible to apply.

Dr Paul Millner from the faculty of biological sciences at the University of Leeds says, 'We believe this to be the next generation diagnostic testing. We can now detect almost any analyte - a substance associated with disease - faster, cheaper and more easily than the current accepted testing methodology. We think this could revolutionise detection.'

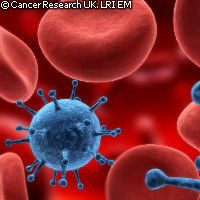

The ELISHA device, which could be on sale in three years, is currently the size of a credit-card payment machine, but the consortium plans to slim it down to the size of a mobile phone. It uses nanotechnology - manipulation of matter at microscopic scales - to detect biomarkers in blood or urine. It then gives a yes or no answer to the presence of a particular disease. Different microchips are inserted in the device to test for different diseases.

Dr Millner says, 'We've designed simple instrumentation to make the biosensors easy to use and understand. They will work in a format similar to the glucose biosensor testing kits that diabetics currently use.'

The device could be used to identify a wide variety of diseases including prostate and ovarian cancer, strokes, heart disease, multiple sclerosis and fungal infections. The ELISHA consortium believes that it could also be versatile enough to detect tuberculosis and HIV. Its swiftness of response will mean both faster diagnosis of disease and referral to consultants.

The ELISHA technology has great potential for the future. ELISHA project manager Dr Tim Gibson says, 'The analytes used in our research only scratch the surface of the potential applications. We've also shown that it can be used in environmental applications, for example to test for herbicides or pesticides in water and antibiotics in milk.'