Jan 26 2009

Scientists from Cambridge University have developed a light, flexible, and strong type of carbon nanotube material that may bring space elevators closer to reality. Motivated by a $4 million prize from NASA, the scientists found a way to combine multiple separate nanotubes together to form long strands. Until now, carbon nanotubes have been too brittle to be formed into such long pieces.

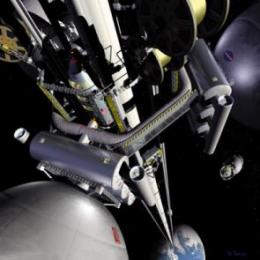

A space elevator would extend 22,000 miles above the Earth to a station, and then another 40,000 miles to a weighted structure for stability.

A space elevator would extend 22,000 miles above the Earth to a station, and then another 40,000 miles to a weighted structure for stability.

And a space elevator - if it ever becomes reality - will be quite long. NASA needs about 144,000 miles of nanotube to build one. In theory, a cable would extend 22,000 miles above the Earth to a station, which is the distance at which satellites remain in geostationary orbit. Due to the competing forces of the Earth's gravity and outward centrifugal pull, the elevator station would remain at that distance like a satellite. Then the cable would extend another 40,000 miles into space to a weighted structure for stability. An elevator car would be attached to the nanotube cable and powered into space along the track.

NASA and its partner, the Spaceward Foundation, hope that a space elevator could serve as a cost-effective and relatively clean mode of space transportation. NASA's current shuttle fleet is set to retire in 2010, and the organization doesn't have enough funds to replace it until 2014 at the earliest. To fill the gap, NASA is hiring out shuttles to provide transportation to the International Space Station from private companies.

So NASA could use a space elevator, the sooner the better. Space elevators could lift material at just one-fifth the cost of a rocket, since most of a rocket's energy is used simply to escape Earth's gravity. Not only could a space elevator offer research expeditions for astronauts, the technology could also expand the possibilities for space tourism and even space colonization.

Currently, the Cambridge team can make about 1 gram of the new carbon material per day, which can stretch to 18 miles in length. Alan Windle, professor of materials science at Cambridge, says that industrial-level production would be required to manufacture NASA's request for 144,000 miles of nanotube. Nevertheless, the web-like nanotube material is promising.

"The key thing is that the process essentially makes carbon into smoke, but because the smoke particles are long thin nanotubes, they entangle and hold hands," Windle said. "We are actually making elastic smoke, which we can then wind up into a fiber."

Windle and his colleagues presented their results last month at a conference in Luxembourg, which attracted hundreds of attendees from groups such as NASA and the European Space Agency. John Winter of EuroSpaceward, which organized the conference, thought the new material was a significant step.

"The biggest problem has always been finding a material that is strong enough and lightweight enough to stretch tens of thousands of miles into space," said Winter. "This isn't going to happen probably for the next decade at least, but in theory this is now possible. The advances in materials for the tether are very exciting."