Jun 26 2009

It is now possible to engineer tiny containers the size of a virus to deliver drugs and other materials with almost 100 percent efficiency to targeted cells in the bloodstream.

According to a new Cornell study, the technique could one day be used to deliver vaccines, drugs or genetic material to treat cancer and blood and immunological disorders. The research is published today (June 25, 2009) online at the Web site of the journal Gene Therapy.

"This study greatly extends the range of therapies," said Michael King, Cornell associate professor of biomedical engineering, who co-authored the study with lead author Zhong Huang, a former Cornell research associate who is now an assistant professor at the Shenzhen University School of Medicine in China. "We can introduce just about any drug or genetic material that can be encapsulated, and it is delivered to any circulating cells that are specifically targeted," King added.

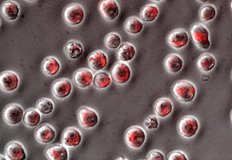

The technique involves filling the tiny lipid containers, or nanoscale capsules, with a molecular cargo and coating the capsules with adhesive proteins called selectins that specifically bind to target cells. A shunt coated with the capsules is then inserted between a vein and an artery. Much as burrs attach to clothing in a field, the selectin-coated capsules adhere to targeted cells in the bloodstream.

After rolling along the shunt wall, the cells break free from the wall with the capsules still attached and ingest their contents.

The technique mimics a natural immune response that occurs during inflammation, which stimulates cells on blood vessel walls to express selectins, which quickly form adhesive bonds with passing white blood cells. The white blood cells then stick to the selectins and roll along the vessel wall before leaving the bloodstream to fight disease or infection.

Selectin proteins may be used to specifically target nucleated (cells with a nucleus) cells in the bloodstream.

The study shows that since only the targeted cells ingest the contents of the nanocapsules, the technique could greatly reduce the adverse side effects caused by some drugs.

In a previous paper, King showed how metastasizing cancer cells circulating in the blood stream can stick to selectin-coated devices containing a second protein that programs cancer cells to self-destruct.

Said King, "We've found a way to disable the function of cancer cells without compromising the immune system," which is a problem with many other therapies directed against metastasis.

The current study demonstrates that genetic material can be delivered to targeted cells to turn off specific genes and interfere with processes that lead to disease. The researchers filled nanocapsules with a small-interfering RNA (siRNA) and targeted them to specific circulating cells. When the targeted cells ingested the capsules, the siRNA turned off a gene that produces an enzyme that contributes to the degradation of cartilage in arthritis.

In a similar manner, the method could be used to target the delivery of chemotherapy drugs, vaccine antigens to white blood cells, specific molecules that mitigate auto-immune disorders and more, King said.