Jul 15 2009

Physicists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have overcome a hurdle in quantum computer development, having devised* a viable way to manipulate a single "bit" in a quantum processor without disturbing the information stored in its neighbors. The approach, which makes novel use of polarized light to create "effective" magnetic fields, could bring the long-sought computers a step closer to reality.

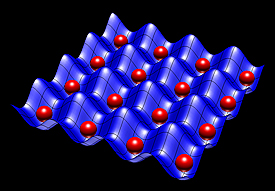

Optical lattices use lasers to separate rubidium atoms (red) for use as information “bits” in neutral-atom quantum processors—prototype devices that designers are trying to develop into full-fledged quantum computers. NIST scientists have managed to isolate and control pairs of the rubidium atoms with polarized light, an advance that may bring quantum computing a step closer to reality.

Credit: NIST

Optical lattices use lasers to separate rubidium atoms (red) for use as information “bits” in neutral-atom quantum processors—prototype devices that designers are trying to develop into full-fledged quantum computers. NIST scientists have managed to isolate and control pairs of the rubidium atoms with polarized light, an advance that may bring quantum computing a step closer to reality.

Credit: NIST

A great challenge in creating a working quantum computer is maintaining control over the carriers of information, the "switches" in a quantum processor, while isolating them from the environment. These quantum bits, or "qubits," have the uncanny ability to exist in both "on" and "off" positions simultaneously, giving quantum computers the power to solve problems conventional computers find intractable-such as breaking complex cryptographic codes.

One approach to quantum computer development aims to use a single isolated rubidium atom as a qubit. Each such rubidium atom can take on any of eight different energy states, so the design goal is to choose two of these energy states to represent the on and off positions. Ideally, these two states should be completely insensitive to stray magnetic fields that can destroy the qubit's ability to be simultaneously on and off, ruining calculations. However, choosing such "field-insensitive" states also makes the qubits less sensitive to those magnetic fields used intentionally to select and manipulate them.

"It's a bit of a catch-22," says NIST's Nathan Lundblad. "The more sensitive to individual control you make the qubits, the more difficult it becomes to make them work properly."

To solve the problem of using magnetic fields to control the individual atoms while keeping stray fields at bay, the NIST team used two pairs of energy states within the same atom. Each pair is best suited to a different task: One pair is used as a "memory" qubit for storing information, while the second "working" pair comprises a qubit to be used for computation. While each pair of states is field-insensitive, transitions between the memory and working states are sensitive and amenable to field control. When a memory qubit needs to perform a computation, a magnetic field can make it change hats. And it can do this without disturbing nearby memory qubits.

The NIST team demonstrated this approach in an array of atoms grouped into pairs, using the technique to address one member of each pair individually. Grouping the atoms into pairs, Lundblad says, allows the team to simplify the problem from selecting one qubit out of many to selecting one out of two-which, as they show in their paper, can be done by creating an effective magnetic field, not with electric current as is ordinarily done, but with a beam of polarized light. The polarized-light technique, which the NIST team developed, can be extended to select specific qubits out of a large group, making it useful for addressing individual qubits in a quantum processor without affecting those nearby.

"If a working quantum computer is ever to be built," Lundblad says, "these problems need to be addressed, and we think we've made a good case for how to do it." But, he adds, the long-term challenge to quantum computing remains: integrating all of the required ingredients into a single apparatus with many qubits.