Nov 29 2012

Tufts University School of Engineering researchers have demonstrated silk-based implantable optics that offer significant improvement in tissue imaging while simultaneously enabling photo thermal therapy, administering drugs and monitoring drug delivery. The devices also lend themselves to a variety of other biomedical functions.

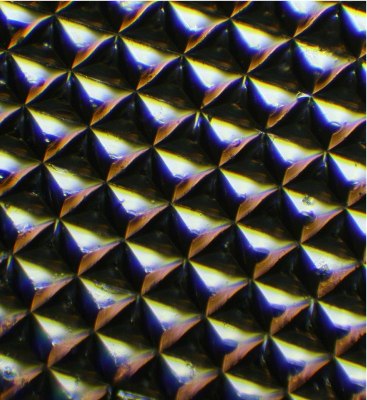

Microscopic image of a silk optical implant created when purified silk protein is poured into molds in the shape of multiple micro-sized reflectors and then air-dried. When implanted in tissue and illuminated, the "silk mirrors" caused more light to be reflected from within the tissue allowing for enhanced imaging. Later, the reflector was harmlessly reabsorbed in living tissue and did not need to be removed. (Photo: Fiorenzo Omenetto)

Microscopic image of a silk optical implant created when purified silk protein is poured into molds in the shape of multiple micro-sized reflectors and then air-dried. When implanted in tissue and illuminated, the "silk mirrors" caused more light to be reflected from within the tissue allowing for enhanced imaging. Later, the reflector was harmlessly reabsorbed in living tissue and did not need to be removed. (Photo: Fiorenzo Omenetto)

Biodegradable and biocompatible, these tiny mirror-like devices dissolve harmlessly at predetermined rates and require no surgery to remove them.

The technology is the brainchild of a research team led by Fiorenzo Omenetto, Frank C. Doble Professor of Engineering at Tufts. For several years, Omenetto; David L. Kaplan, Stern Family Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Biomedical Engineering chair, and their colleagues have been exploring ways to leverage silk's optical capabilities with its capacity as a resilient, biofriendly material that can stabilize materials while maintaining their biochemical functionality.

The technology is described in the paper "Implantable Multifunctional Bioresorbable Optics," published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences online Early Edition the week of November 12, 2012.

"This work showcases the potential of silk to bring together form and function. In this case an implantable optical form -- the mirror -- can go beyond imaging to serve multiple biomedical functions," Omenetto says.

Turning Silk into Mirrors

To create the optical devices, the Tufts bioengineers poured a purified silk protein solution into molds of multiple micro-sized prism reflectors, or microprism arrays (MPAs). They pre-determined the rates at which the devices would dissolve in the body by regulating the water content of the solution during processing. The cast solution was then air dried to form solid silk films in the form of the mold. The resulting silk sheets were much like the reflective tape found on safety garments or on traffic signs.

When implanted, these MPAs reflected back photons that are ordinarily lost with reflection-based imaging technologies, thereby enhancing imaging, even in deep tissue.

The researchers tested the devices using solid and liquid "phantoms" (materials that mimic the scattering that occurs when light passes through human tissue). The tiny mirror-like devices reflected substantially stronger optical signals than implanted silk films that had not been formed as MPAs.

Preventing Infection, Fighting Cancer

The Tufts researchers also demonstrated the silk mirrors’ potential to administer therapeutic treatments.

In one experiment, the researchers mixed gold nanoparticles in the silk protein solution before casting the MPAs. They then implanted the gold-silk mirror under the skin of mice. When illuminated with green laser light, the nanoparticles converted light to heat. Similar in-vitro experiments showed that the devices inhibited bacterial growth while maintaining optical performance.

The team also embedded the cancer-fighting drug doxorubicin in the MPAs. The embedded drug remained active even at high temperatures (60 degree C), underscoring the ability of silk to stabilize chemical and biological dopants.

When exposed to enzymes in vitro, the doxorubicin was released as the mirror gradually dissolved. The amount of reflected light decreased as the mirror degraded, allowing the researchers to accurately assess the rate of drug delivery.

"The important implication here is that using a single biofriendly, resorbable device one could image a site of interest, such as a tumor, apply therapy as needed and then monitor the progress of the therapy," says Omenetto.

Collaborating with Omenetto and Kaplan from Tufts Department of Biomedical Engineering were Hu Tao, research assistant professor; Jana M. Kainerstorfer, post-doctoral researcher; Sean M. Siebert, a Tufts undergraduate; Eleanor M. Pritchard, former post-doctoral researcher; Angelo Sassaroli, research assistant professor; Bruce J.B. Panilaitis, research assistant professor; Mark A. Brenckle, graduate student; Jason Amsden, former post-doctoral researcher; Jonathan Levitt, post-doctoral researcher, and Professor Sergio Fantini.

At Tufts, Fiorenzo Omenetto also has an appointment in the Department of Physics in the School of Arts and Sciences, and David Kaplan also has appointments in the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, the Department of Chemistry in the School of Arts and Sciences, the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences, and the School of Dental Medicine.

The work was supported by the United States Army Research Laboratory, the United States Army Research Office, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the Tissue Engineering Resource Center of the National Institutes of Health under award number P41EB00250 and the National Science Foundation.