Jan 10 2013

When you get a cut, blood starts to flow from the wound. But very quickly, complex biochemical processes spring into action, creating a scaffolding of molecules to block the hole, and then building up an impervious clot to stanch the flow.

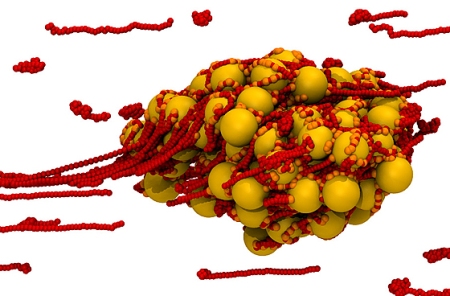

The first stage of blood clotting is the formation of a plug, seen here, which is made up of platelets (seen in gold) and structures called von Willebrand Factor (vWF), seen in red. The vWF structures are normally present in blood in coiled up form, but in the presence of the flow from a bleeding wound they unfurl to form long, sticky strands, which bind the platelets together. Image: Hsieh Chen

The first stage of blood clotting is the formation of a plug, seen here, which is made up of platelets (seen in gold) and structures called von Willebrand Factor (vWF), seen in red. The vWF structures are normally present in blood in coiled up form, but in the presence of the flow from a bleeding wound they unfurl to form long, sticky strands, which bind the platelets together. Image: Hsieh Chen

That process relies on a set of molecules that constantly flow through the body’s veins and arteries, just waiting to spring into action when needed. When their job is done, they dissolve back into the blood, awaiting their next repair job.

A team of MIT researchers has analyzed the process and found, for the first time, exactly how the different molecular components work together to block the flow of blood from a cut. Now, they are working on applying that knowledge to the development of synthetic materials that could be used to control different kinds of liquid flows, and could lead to a variety of new self-assembling materials.

The research is published this week in the online journal Nature Communications, in a paper co-authored by MIT assistant professor of materials science and engineering Alfredo Alexander-Katz, graduate student Hsieh Chen, and six other researchers in the United States, Germany and Austria.

Stopping a leak the way blood does

One of the surprising things the team found out is that the increased flow rate caused by a wound automatically triggers the reaction that plugs the hole: The faster the flow, the more effectively it works. That’s a counterintuitive finding, since faster flows usually stir things up rather than causing them to clump together.

The way the molecules in the bloodstream react to a leak “is something very freaky,” Alexander-Katz says. “Part of it is chemistry, and part of it is mechanical, which has to do with the flow itself.”

The key molecule, he explains, is a biopolymer — a long, chainlike structure — called the von Willebrand factor (vWF), named for a disease in which it is suppressed in the bloodstream. This molecule normally flows through the bloodstream in a rolled-up form in which it is essentially inactive.

However, “as soon as you stretch [vWFs], they become sticky,” Alexander-Katz says. He compares the reaction to a roll of adhesive tape: It’s only when you pull the tape out from the roll that the sticky part is exposed and begins to attach to things. In the case of these molecules in the blood, in an increased rate of flow, he says, “you stretch them out, and they become sticky and begin sticking to platelets.” The vWFs begin to form a network over the cut — a mixture of the sticky molecules and platelets — that forms a plug within seconds. Over time, additional cells accumulate to form a clot.

If this process were uncontrolled, such plugs would form constantly in the bloodstream, Alexander-Katz says. To counteract that, another kind of molecule also circulates: a kind of “molecular scissors,” he says, that “comes around and cuts [the plugs] to pieces.”

Most of the time, the clumping and snipping remain in balance, so no clots form. But when the flow rate increases, the vWF molecules stretch and grow stickier, and the “molecular scissors” can’t keep up — so the plug builds up.

One reason this process interests materials scientists is that most biochemical materials, such as shells or bones, form extremely slowly. But clotting takes place rapidly — so these insights could lead to solid structural materials that can form quickly.

The flow-induced clumping, the team writes in its report, is “a completely new aggregation paradigm.” Alexander-Katz says that this process “seems to be a transition [from one chemical state to another] that hasn’t been studied before,” as well as a universal behavior that depends primarily on the shapes of polymers and particles.

What’s more, the process is reversible: When the flow rate slows down, the plugs disaggregate anew. By selecting different polymer building blocks, it’s possible to “tune” the material to clump up at any specific flow-rate, he says.

“I think we can start making all kinds of different aggregates that depend on flow conditions,” Alexander-Katz says. There may be a number of possible applications for inks, pigments and coatings, he suggests, or for devices such as self-healing tires. “There are so many processes where you have flows,” he says.

Evan Sadler, a professor of medicine and of biochemistry and molecular biophysics at Washington University in St. Louis, says, “I find it fascinating that a relatively simple model may account for the behavior of platelets and von Willebrand factor in flowing blood.” He adds that all animals have this factor, and all have platelets, but the sizes of platelets and the rates of blood flow vary greatly. This work, he says, “may help us to understand how the binding characteristics of vWF and platelets have been tuned by evolution to maintain normal hemostatic function across such a large range of conditions.”

In addition to MIT, the team included researchers from Boston University; the University of Augsburg and Heidelberg Ruprecht-Karls University, in Germany; and Baxter Innovations, of Vienna. It was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and the German Research Foundation.