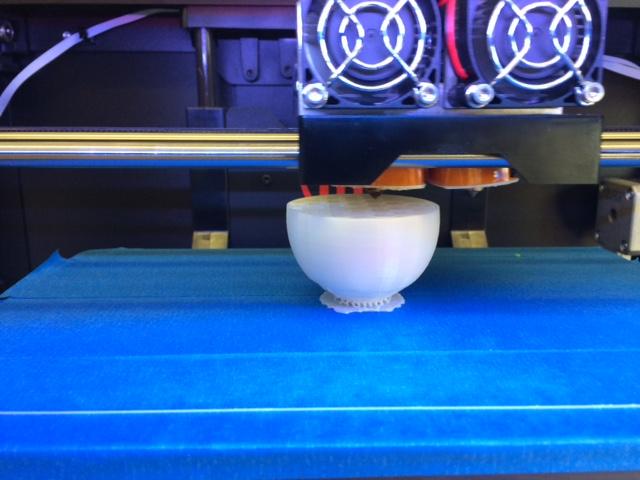

A partially manufactured egg inside a 3D printer

Image credit: Miri Dainson and Robert Pecchia

New research that studied the benefits of using 3D printing to see how birds reject eggs has been published in the PeerJ journal. Brood parasites try to slip their eggs into other bird’s nests. However, birds have the ability to identify and reject these eggs.

Researchers used artificial eggs made out of wood, plaster and other materials in studies prior to using 3D printers. However, they had significant limitations.

Brood parasites have been successful in sneaking their eggs into birds' nests, and the host birds have raised these chicks believing that they were their own. This has often affected the raising of their own chicks.

An evolutionary arms race has taken place in certain species, and host parents seem to have improved their ability to identify and reject eggs that are not theirs. They make use of cues such as the size, pattern, color and shape of the intruder egg. However, the brood parasites have improved their ability in producing eggs that mimic those of the host species.

Ornithologists have been studying this phenomenon for a long time to find out the manner in which birds identify impostor eggs. They added artificial eggs into nests and studied the reaction of the parent birds.

Egg Lapse

Video 1: For a timelapse video of a 3D model egg being printed,

Video credit: Hunter College, CUNY Communication Office / YouTube

American robin rejecting a 3D model egg

Video 2: For a video of a robin rejecting a 3D model egg (Supplemental File 1 from the article),

Video credit: Mark Hauber / YouTube

However, creating fake eggs that mimic the original eggs using materials such as plaster-of-Paris, wood or plastic has been difficult. These artificial eggs are difficult to replicate accurately and it takes a long time to produce them. Furthermore, human error can also affect their fabrication. In addition to this, accurate replication is required to confirm findings by other researchers.

In order to overcome these restrictions, the researchers used 3D printers to create digital egg models of a North American brood parasite bird – the Brown-headed Cowbirds. 3D printing technology allowed the researchers to create hollow eggs. These eggs could then be filled with gel or water, so that their thermodynamic properties and weight matched those of the real eggs.

The researchers painted the 3D printed eggs with blue-green color so that they matched real eggs of American robins, and in beige color to match the real eggs of cowbirds. These eggs were then slipped into robin nests, and the reaction of the parent birds was observed for six days. All of the blue-green eggs were accepted by the robins. However, 79% of the beige color eggs were rejected. The results of this study were similar to results obtained in earlier studies that used artificial plaster eggs, created using traditional methods.

Hosts of brood parasites vary widely in how they respond to parasitic eggs, and this raises lots of cool questions about egg mimicry, the visual system of birds, the ability to count, cognitive rules about similarity, and the biomechanics of picking things up.

Professor Don Dearborn

Chair of the Biology Department and Brood Parasitism Expert

Bates College

However, 3D-printed eggs can be reproduced to specific shapes and sizes, and with less variance. Furthermore, the digital models can be shared, which would allow replication of the experiments by other researchers without a reduction in accuracy or confidence in results.

"For decades, tackling these questions has meant making your own fake eggs -- something we all find to be slow, inexact, and frustrating. This study uses 3D printing for a more nuanced and repeatable egg-making process, which in turn will allow more refined experiments on host-parasite coevolution." said Prof. Don Dearborn who was not involved in the 3D printing study. "I'm also hopeful that this method can be extended to making thin-shelled, puncturable eggs, which would overcome another one of the constraints on these kinds of behavioral experiments."

"3D printing technology is not just in our future -- it has already revolutionized medical and basic sciences," said Prof. Mark Hauber, an animal behaviorist at Hunter College of the City University of New York, the study's senior author. "Now it steps out into the world of wild birds, allowing standardized egg rejection experiments to be conducted throughout the world."