A new kind of tunable catalyst has been developed by researchers at MIT and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

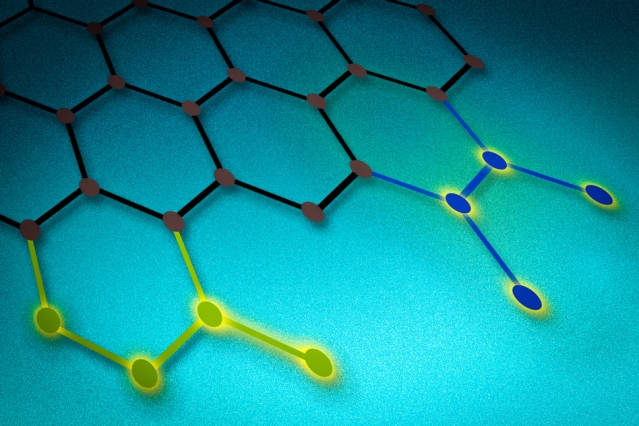

Artist’s rendering of a new carbon-based catalyst that can bond to the edges of two-dimensional sheets of graphene. Illustration: Jose-Luis Olivares/MIT

Artist’s rendering of a new carbon-based catalyst that can bond to the edges of two-dimensional sheets of graphene. Illustration: Jose-Luis Olivares/MIT

Chemical reactions can be promoted by tuning the new carbon-based catalyst. Such catalysts could replace costly rare metals that are currently used in fuel cells.

The newly developed catalyst is made of graphite, with additional compounds attached to the edges of the 2D sheets of graphene that the material is composed of. The catalyst’s characteristics can be tuned to promote specific chemical reactions by altering the composition and the quantities of the additional compounds.

Yogesh Surendranath, assistant professor of chemistry at MIT, along with his team, has described the new catalyst in JACS – the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Catalysts only promote chemical reactions — they do not take part in the process. The repeated action of even minute amounts of a catalyst is known to have a huge and enduring impact on the process.

The electrocatalysts important for promoting reactions in devices like electrolyzers or fuel cells are of two types – molecular or heterogeneous. Molecular electrocatalysts can be easily tuned through chemical treatment. Therefore, their selectivity and reactivity can be customized as per the application needs. Conversely, heterogeneous electrocatalysts cannot be tuned precisely. They are known for their durability and ease of processing into a device.

“What we wanted to do was to figure out a way to bridge those two worlds,” Surendranath explains.

Surendranath’s team worked towards creating a bridge between both types of catalysts by finding ways to chemically modify graphite’s structure to provide the desired tunability.

Surendranath said that pure carbon, dubbed as ‘the universal electrode material’ for batteries and fuel cells, is the base material. By making this material tunable like molecular catalysts, the researchers are creating new design methodologies for such materials. These materials are important components in a number of chemical manufacturing processes.

Surendranath explained that apart from fuel cell applications, the new catalysts could also promote chemical reactions like reduction of carbon dioxide for conversion into a usable fuel. Use of such catalysts helps minimize the emission of a principal greenhouse gas, which brings about climate change, and convert it into a renewable and useful fuel.

“The initial finding described in this paper is just one piece of what we believe is a large iceberg,” Surendranath adds, since the basic ingredient is “a dirt cheap material that we are modifying using well-known chemistry.”

The most common roadblock in converting systems that worked in laboratories into practical market solutions is the inability to scale up the production process. “You need to be able to scale efficiently,” Surendranath says. The fact that the basis for the new catalyst is “a class of materials that are already made at scale, for commodities like paint and rubber,” should make scaling up their process relatively straightforward, he says; “All the keys to that are already in place.”

Surendranath says that this finding is particularly exciting because chemists “usually take a very precise refined material and then engineer some of its properties. But in this case, it allows us to take a material that is cheap and abundant, and turn it into something very valuable. It’s a different paradigm.”

The U.S. Department of Energy partly supported this research work.

Postdoc Tomohiro Fukushima at MIT, and Walter Drisdell and Junko Yano at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California were also part of the research team.