Aug 22 2016

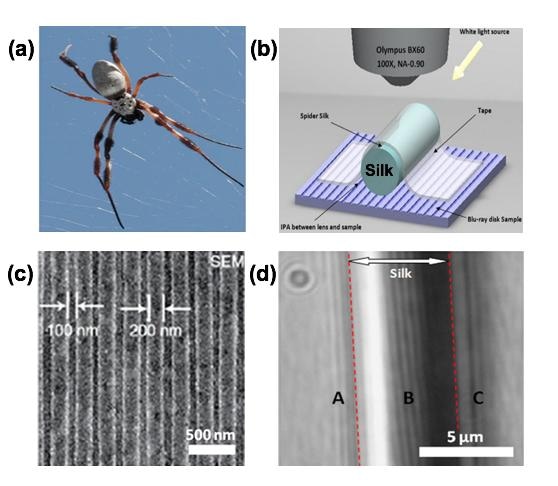

(a) Nephila edulis spider in its web. (b) Schematic drawing of reflection mode silk biosuperlens imaging. The spider silk was placed directly on top of the sample surface by using a soft tape, which magnify underlying nano objects 2-3 times (c) SEM image of Blu-ray disk with 200/100nm groove and lines (d) Clear magnified image (2.1x) of Blu-ray disk under spider silk superlens. (Credit: Bangor University/ University of Oxford)

(a) Nephila edulis spider in its web. (b) Schematic drawing of reflection mode silk biosuperlens imaging. The spider silk was placed directly on top of the sample surface by using a soft tape, which magnify underlying nano objects 2-3 times (c) SEM image of Blu-ray disk with 200/100nm groove and lines (d) Clear magnified image (2.1x) of Blu-ray disk under spider silk superlens. (Credit: Bangor University/ University of Oxford)

A team of researchers from UK’s Bangor and Oxford universities have been able to increase the potential of the microscope using spider-silk as a superlens. A way to extend the resolution of a classical microscope has been long sought after in the field of microscopy.

Objects measuring smaller than 200 nm – the smallest size of bacteria, cannot be viewed using a normal microscope alone due to the physical laws of light. However, superlenses capable of allowing scientists to see beyond the existing magnification have been the goal in recent past.

Shortly after a team at Bangor University’s School of Electronic Engineering published a paper describing a nanobead-derived superlens that was used to break the perceived resolution barrier for the first time, the same team has now accomplished another feat where a naturally occurring biological material was used as a superlens for the first time.

This team was led by Dr Zengbo Wang and in partnership with Prof. Fritz Vollrath’s silk group at Oxford University’s Department of Zoology.

They used a naturally occurring material – dragline silk taken from the golden web spider - as an supplementary superlens, to be placed on top of the surface of the material to be viewed, to provide an extra 2-3 times magnification.

The research findings have been published in Nano Letters, and it illustrates how a cylindrical piece of spider silk taken from the thumb-sized Nephila spider was used as a lens.

We have proved that the resolution barrier of microscope can be broken using a superlens, but production of manufactured superlenses involves some complex engineering processes which are not widely accessible to other researchers. This is why we have been interested in looking for naturally occurring superlenses provided by ‘Mother Nature’, which may exist around us, so that everyone can access superlenses.

Dr Zengbo Wang, Bangor University

Prof Fritz Vollrath adds, “It is very exciting to find yet another cutting edge and totally novel use for a spider silk, which we have been studying for over two decades in my laboratory.”

These lenses can be applied to see and view formerly ‘invisible’ structures, such as biological micro-structures and engineered nano-structures. It can also potentially be used to view native viruses and germs.

These silks make perfect candidates due to their natural cylindrical structure at a micron- and submicron-scale. In this particular case the diameters of individual filaments measured one tenth of a thin human hair.

The spider filament facilitated viewing of details on a blue- ray disk or a micro-chip which would be invisible using the unchanged optical microscope.

It is quite similar to when looking through a cylindrical bottle or glass, the clearest image can only be found along the narrow strip immediately opposite the viewer’s line of vision, or resting on the surface being examined, the single filament offers a 1D viewing image along its length.

The cylindrical silk lens has advantages in the larger field-of-view when compared to a microsphere superlens. Importantly for potential commercial applications, a spider silk nanoscope would be robust and economical, which in turn could provide excellent manufacturing platforms for a wide range of applications.

Dr Zengbo Wang, Bangor University

James Monks, a co-author on the paper comments: “it has been an exciting time to be able to develop this project as part of my honours degree in electronic engineering at Bangor University and I am now very much looking forward to joining Dr Wang’s team as a PhD student in nano-photonics.”