Jan 31 2017

Heart failure affects approximately 6 million adults in the United States and is a contributing cause in one of every nine deaths. For those afflicted with heart failure, about half of them will die within five years of being diagnosed. In addition to the human toll, the condition is estimated to cost the country somewhere around $30 billion per year. The condition is caused when there is a weakening of the heart muscle, preventing it from pumping a sufficient amount of blood to meet the needs of the body for blood and oxygen. This weakening is one of the most common reasons why people over the age of 65 are admitted to hospitals.

[Source: Cardiovascular Business]

[Source: Cardiovascular Business]

The good news is that a diagnosis of heart failure is not necessarily a death sentence. With proper diagnosis and ongoing treatment, the symptoms can improve and it is possible to learn to manage them in order to live a full and enjoyable life. The best way to avoid the symptoms of heart failure, however, are to avoid doing long term damage to your heart in the first place. This means doing things like not smoking, or quitting if you have already started, eating healthy, getting regular exercise, and maintaining a healthy weight, among other general lifestyle measures.

Researchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and the University of Minnesota (UM) are working to help people who have already suffered a heart attack to reduce the risk that the damage incurred during the attack will lead to heart failure. The research team, led by Jianyi “Jay” Zhang, MD, PhD of UAB and Brenda Ogle, PhD at UM, investigated the possibilities for growing engineered heart tissue to aid in the regeneration of muscle after a heart attack, something the heart cannot do on its own. They used a one-micron-resolution scaffold that was created by a 3D printer to serve as a scaffold for turning human cells into a heart tissue muscle patch that will actually beat in rhythm.

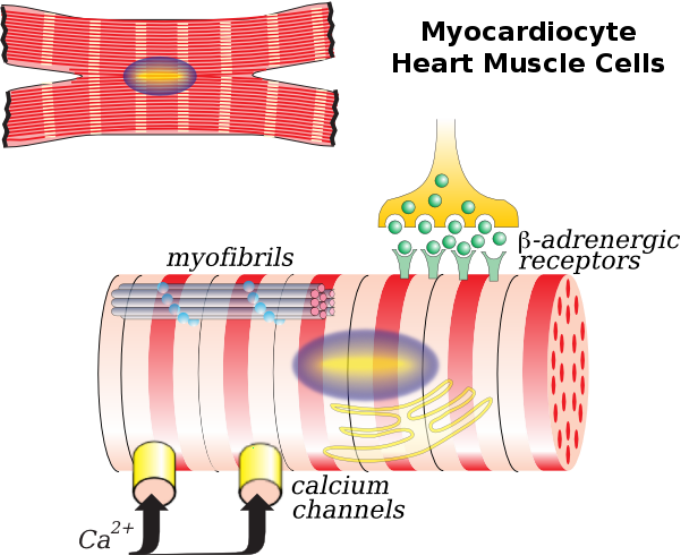

To create this patch, they mixed together a total of 50,000 cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells. Cardiomyocytes are the smooth muscle cells that contain myofibrils, specialized structures known as organelles which are the fundamental contracting unit of the heart. Endothelial cells are the famously controversial human stem cells that have become such a central part of (re)generating various cellular structures necessary in transplant operations. This combination, when mixed together and placed on the scaffold, actually began beating with one day of seeding and grew in strength over the following weeks. At no point did it become sentient and crawl across the table only to star in a Irvin Yeaworth film, so don’t panic.

In fact, this amazing creation was tested by placing it in the hearts of mice who had suffered from heart attacks, probably as a result of their stressful jobs and the fact that no matter how hard they work, they generally get overlooked for that big promotion. The results of these experiments, which were published in Circulation Research, found that there was a significant improvement in the function of the mice’s hearts and a decrease in the presence of dead tissue after the patches were placed. The researchers explained the significance of their findings:

“[T]he cardiac muscle patches produced for this report may represent an important step toward the clinical use of 3D-printing technology. To our knowledge, this is the first time modulated raster scanning has ever been successfully used to control the fabrication of a tissue-engineered scaffold, and consequently, our results are particularly relevant for applications that require the fibrillar and mesh-like structures present in cardiac tissue.”

While this may be the first time for this specific type of tissue scaffolding, the potential for it has been seen before and is being recognized by members of the medical community more than ever. The ability of 3D printers to create something at such a small scale with such a great degree of precision makes it the ideal way to fabricate these scaffolds and, in fact, a major reason for the increase in the ability of medical researchers to generate usable tissue for implants.