Feb 19 2018

Thermoelectric materials are known to generate electricity by using thermal differences. Now, a low-cost and environmentally friendly method is available for producing these materials with the most basic of components: a photocopy paper, a normal pencil, and a conductive paint can be used to change a temperature difference into electricity through the thermoelectric effect. This breakthrough has now been revealed by researchers at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin.

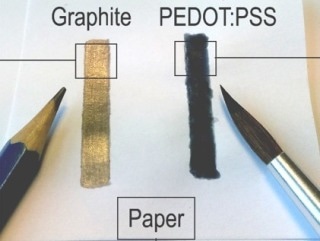

Pencil, paper and co-polymer varnish are sufficient for a thermoelectrical device. (Credit: HZB)

Pencil, paper and co-polymer varnish are sufficient for a thermoelectrical device. (Credit: HZB)

The thermoelectric effect is not a novel concept; in fact, Thomas J. Seebeck discovered this effect about 200 years ago. When two types of metals are brought together, an electrical voltage can be produced if one metal is warmer than the other. This effect enables the remaining heat to be partly converted into electrical energy. This remaining heat is a by-product of nearly all natural and technological processes, for example, in power plants, all household appliances, and even the human body. This heat is one among the largest underutilized energy sources in the globe - and often it is not used completely.

Tiny effect

However, despite being as useful an effect as it is, it is extremely small in common metals. This is because in addition to having high electrical conductivity, metals also have high thermal conductivity. As a result, those differences in temperature disappear instantly. In spite of their high electrical conductivity, thermoelectric materials should have low thermal conductivity. In certain technological applications, thermoelectric devices made of inorganic semiconductor materials, for example bismuth telluride, are already being used. Yet, these types of material systems are very costly and their use only pays off in some situations. Non-toxic, flexible, organic materials based on carbon nanostructures, for instance, are also being studied for use in the human body.

HB pencil and co-polymer varnish

A research team, headed by Prof. Norbert Nickel at the HZB, has now demonstrated that the effect can be achieved much more easily: using a standard HB-grade pencil, the researchers covered over a small region in pencil on a normal photocopy paper. They next applied a conductive, transparent co-polymer paint (PEDOT: PSS) onto the surface, as a second material.

What actually transpires is that a voltage is delivered by the pencil traces on the paper and this voltage is similar to other nanocomposites that are far more expensive and being used for flexible thermoelectric elements. Adding some indium selenide to the pencil’s graphite could increase this voltage tenfold.

Poor heat transport explained

The team studied co-polymer coating films and graphite using spectroscopic methods and a scanning electron microscope (Raman scattering) at HZB.

The results were very surprising for us as well. But we have now found an explanation of why this works so well: the pencil deposit left on the paper forms a surface characterised by unordered graphite flakes, some graphene, and clay. While this only slightly reduces the electrical conductivity, heat is transported much less effectively.

Prof. Norbert Nickel, HZB

Outlook: Flexible Components printed right on paper

In future, these basic constituents could be used to print thermoelectric components onto paper that are non-toxic, environmentally friendly, and extremely inexpensive. Such small and flexible components could be applied directly on the body and could even use the body’s heat to operate tiny sensors or devices.