Liquid crystals contain small defects that exhibit the ability to host chemical reactions or transport cargo, which makes them useful for exciting new technologies, such as synthetic platforms for completely new drug delivery systems, sensors and materials.

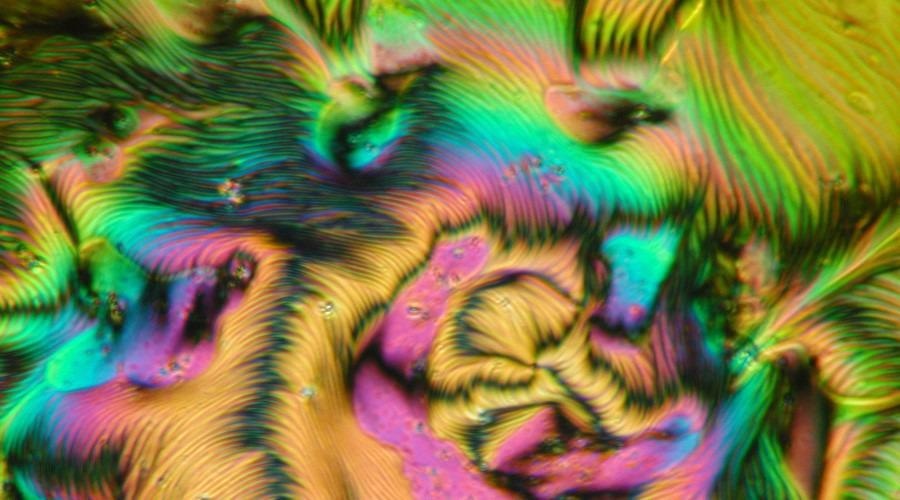

Researchers have shown in simulations that they can precisely control the movement of defects within active liquid crystals, which makes the crystals candidates for technologies like drug delivery systems and sensors. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Researchers have shown in simulations that they can precisely control the movement of defects within active liquid crystals, which makes the crystals candidates for technologies like drug delivery systems and sensors. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Scientists at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) earlier took a step toward such technologies by making liquid crystals that could move independently.

Currently, the same team has demonstrated, through simulations, that it is possible to accurately regulate the movement of defects inside such active liquid crystals by altering the gradient of activity about them. Theoretically, this can be performed by discharging pulses of light or varying the chemical composition in several areas of the system.

Previously, the flows within these liquid crystal systems have been chaotic. Now we have found a way to introduce gradients of activity within the system in a manner that confines and controls molecular motion, without having to use any barriers or obstacles.

Juan de Pablo, Study Lead Researcher and Liew Family Professor of Molecular Engineering, The University of Chicago

The study findings were published in the Physical Review Letters journal on June 2nd, 2021. The other study authors include postdoctoral researchers Rui Zhang, Ali Mozaffari, and Noe Atzin.

Controlling Movements, Creating Patterns

When compared to conventional liquids, liquid crystals display an even molecular order. Such crystals have been utilized in optical technologies, such as communications or displays. However, they can be utilized in highly sophisticated technologies, like capsules implanted in the body to automatically discharge antibodies in response to a virus, or clothing that senses and captures hazardous contaminants present in the air.

One step ahead of developing such technologies is engineering autonomous materials that could be regulated remotely. Earlier, de Pablo and collaborators at UChicago and Stanford University created autonomous liquid crystals by blending in actin filaments — the same filaments that are responsible for the formation of a cell’s cytoskeleton — and “motor” proteins, the proteins used by biological systems to apply force on actin filaments.

In this specific case, the proteins were designed to be light-sensitive, implying their activity increases upon exposure to light.

Through computer simulations, the team discovered that the motion of the liquid crystals can be regulated in circular domains by altering the gradient of low and high activity.

Thus, the researchers concluded they could alter the material’s dynamic states while also making the defects act in certain periodic ways like cruising, dancing, bouncing or holding a steady rotation. The outcomes of such movements can be mapped as complex geometric designs that are reminiscent of drawings made using a Spirograph.

These beautiful trajectories show we can control with incredible precision the motion within these systems.

Juan de Pablo, Study Lead Researcher and Liew Family Professor of Molecular Engineering, The University of Chicago

Understanding Dynamics Within Cells

As a next step, the team is collaborating with experimentalists to test if the same outcomes are obtained in physical systems. Gaining better insights into ways to control such dynamic systems could be a leap toward sensing technologies and also give researchers a hint as to how to comprehend or control materials inside similar systems, like cells.

Perhaps you could get tissue to grow a certain way or another, or get stem cells to differentiate into particular lineages by focusing on the topological defects that naturally arise in biological tissues. Before, we didn’t know if this was possible.

Juan de Pablo, Study Lead Researcher and Liew Family Professor of Molecular Engineering, The University of Chicago

Journal Reference:

Mozaffari, A., et al. (2021) Defect Spirograph: Dynamical Behavior of Defects in Spatially Patterned Active Nematics. Physical Review Letters. doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.227801.