Writing in the journal Materials, scientists have presented a multi-analytical study on Nuragic bronze statues. The study shines light on ancient metallurgical techniques and superficial treatments of bronze statues from this period.

Bronze statuettes: (A) Pigorini Museum (#26065) and (B) Musei Reali Museum (#783). Image Credit: Brunetti, A et al., Materials. Study: The Strange Case of the Nuragic Offerers Bronze Statuettes: A Multi-Analytical Study

Nuragic Bronze Statues

The Nuragic civilization arose on the Italian island of Sardinia around 1700 B.C. The Nuragic peoples are known for their unique architecture called “nuraghe.” Features of nuraghe include truncated conical towers, and so far, 8,000 of these buildings have been discovered by archaeologists.

Aside from their architectural style, the Nuragic peoples are known for their intricate bronze statues and statuettes. Examples of their metallurgical skills include swords, tools, axes, navicelles (which are small models of ships) and several figures representing priests, offerers, and warriors.

However, many Nuragic artifacts were excavated via unscrupulous and illegal means, limiting the knowledge available to archaeologists and scholars on the provenance and archaeological context of findings.

Nuragic Offerer Statuettes

In the past few years, the analysis of statuettes from museums in Rome and Turin have provided new information on the Nuragic people’s metallurgic skills. These statuettes include two solemn female figures of offerers. In their left hands, they are holding what appears to be an offering (possibly to the Gods) and their right hands are open in greeting.

These statuettes have revealed a thick layer of iron-based material covering the head of the offerers, which was a surprising revelation. The body of the statuettes, however, was covered by a different type of corrosion. Interaction of the material and the burial environment cause both types of corrosion.

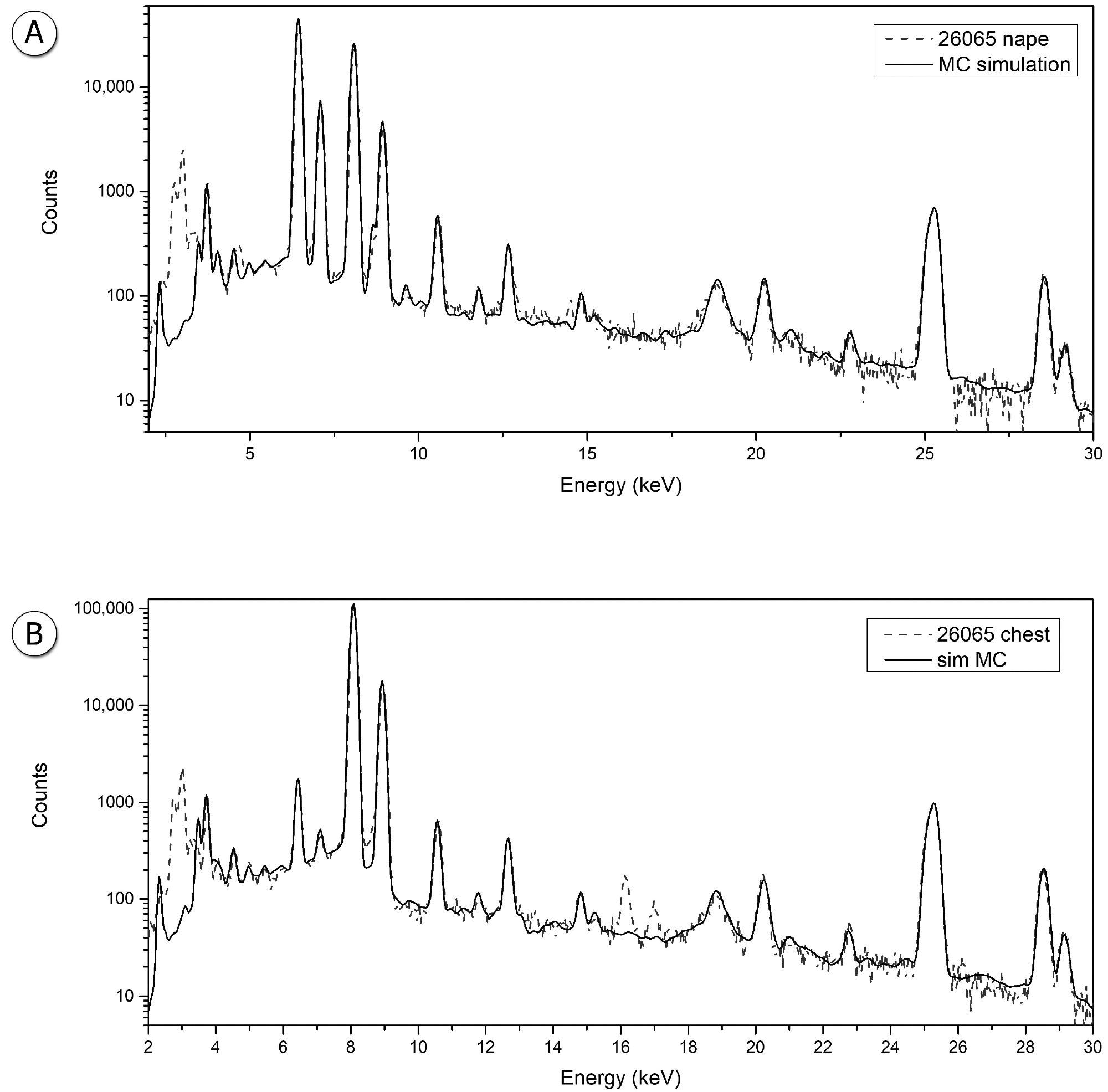

Simulated spectra superimposed to the measured one: sample #26065, (A) nape (B) and chest. Image Credit: Brunetti, A et al., Materials

The Study

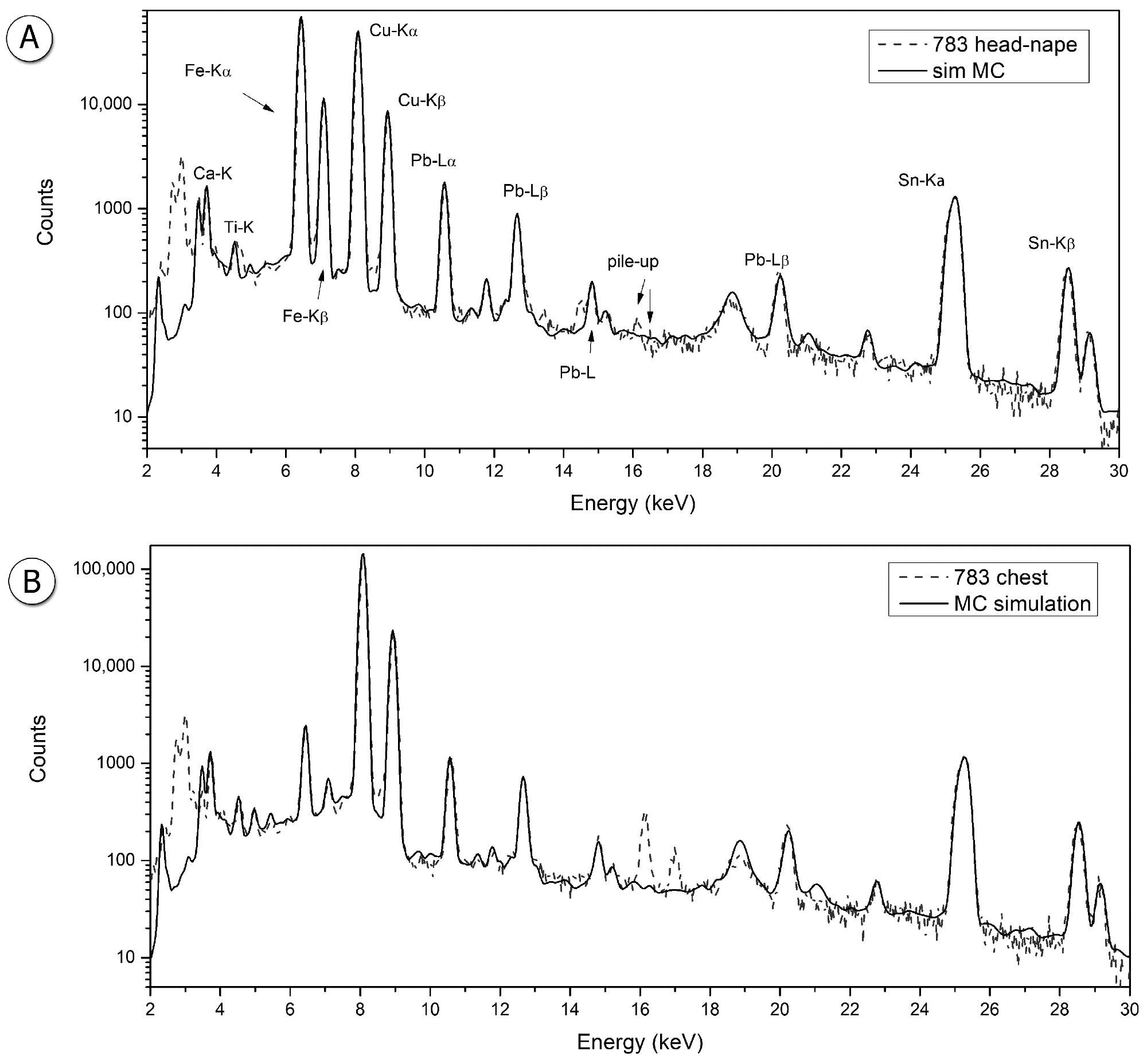

The researchers have employed a multi-analytical approach to investigate these statuettes. An integrated XRF/Monte Carlo simulation technique has been used to analyze the samples. This approach provides a more holistic analysis of the statuettes, including structural characterization, corrosion layer identification, and alloy composition estimation.

Alloy compositions of the statuettes were discovered to be similar, mostly copper with varying contents of tin and lead. Lead contents varied the most, with variations of the other metals within experimental error ranges and alloy variations which are the result of melting processes. Lead was intentionally added to improve the workability of the molten metal.

This ternary alloy was commonly used in the late Bronze age. Aside from improving the workability of the alloy, lead was often used as a filler material due to it being cheaper and more readily available than other alloy metals. Analysis confirmed that an iron-rich layer covered the head of both statuettes.

In both statuettes, the corrosion patinas possess the same chemical elements. These elements are mainly sodium, titanium, calcium, and iron. Elemental composition varies according to the position on the statuette’s body, and each composition zone contains the same concentration variants. This has led the authors to conclude that both statuettes had a common burial site.

The thickness of the protective layer on the heads varied from 40-70 μm. This varied depending on the location analyzed. Analysis also suggested that the presence of iron caused a deeper level of corrosion. One sample was in a better state of conservation than the other, with reduced corrosion levels in one sample indicating the influence of previous cleaning efforts.

The authors have concluded that the protective layer on the heads of the bronze Nuragic statuettes may have a number of explanations, with one likely explanation being for aesthetic appeal. The use of this layer may have produced a chromatic effect.

The lack of this specific corrosion on other areas of the statuette’s body further confirms the hypothesis that this iron coating was specifically used on the head. Furthermore, as iron fusing technology was not developed properly in the Early Iron Age in Sardinia, this further confirms that the layer was most likely used as a decorative one, possibly made of iron-rich paint.

Simulated spectra superimposed to the measured one: sample #783, (A) head (B) and chest. Image Credit: Brunetti, A et al., Materials

In Conclusion

The use of a multi-analytical approach in the study has shed new light on the artisanship from this poorly understood Bronze and Iron Age Mediterranean culture from Sardinia. The results indicate the use of iron-rich coatings on the head of the statuettes, probably as a decorative layer to enhance their aesthetic appeal.

The authors have stated that further, comprehensive analysis on these statuettes will be needed using other techniques such as neutron imaging techniques. Furthermore, the search for other statuettes from the Nuragic period which display this peculiarity will help to build a more complete picture of Nuragic artisanship.

Further Reading

Brunetti, A et al. (2022) The Strange Case of the Nuragic Offerers Bronze Statuettes: A Multi-Analytical Study Materials 15(12) 4174 [online] mdpi.com. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/15/12/4174

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.