Apr 14 2011

Easy-to-follow recipes for radioactive compounds like those found in nuclear fuel storage pools, liquid waste containment areas and other contaminated aqueous environments have been developed by researchers at Sandia National Laboratories.

"The need to understand the chemistry of these compounds has never been more urgent, and these recipes facilitate their study," principal investigator May Nyman said of her group's success in encouraging significant amounts of relevant compounds to self-assemble.

The trick to the recipes is choosing the right templates. These are atoms or molecules that direct the growth of compounds in much the way islands act as templates for coral reefs.

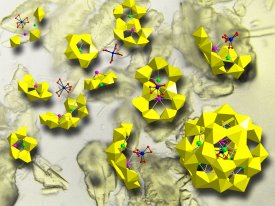

The diagrammatic image, viewed from upper left to bottom right, shows steps in the templated creation of radioactive compounds. In this case, the red spidery-looking shape is oxygen building a cage around tantalum (blue sphere) ; green sphere is potassium, pink is cesium. The yellow boxes are uranyl peroxide. Chemical attractions force the disparate parts to self-assemble. The background is a transmitted light-microscope image of crystals of the final product, U28.

The diagrammatic image, viewed from upper left to bottom right, shows steps in the templated creation of radioactive compounds. In this case, the red spidery-looking shape is oxygen building a cage around tantalum (blue sphere) ; green sphere is potassium, pink is cesium. The yellow boxes are uranyl peroxide. Chemical attractions force the disparate parts to self-assemble. The background is a transmitted light-microscope image of crystals of the final product, U28.

The synthesized materials are stable, pure and can be studied in solution or as solids, making it easier to investigate their chemistry, transport properties and related phases.

The compounds are bright yellow, soluble peroxides of uranium called uranyl peroxide. These and related compounds may be present in any liquid medium used in the nuclear fuel cycle. They also appear in the environment from natural or human causes.

Made with relatively inexpensive and safe depleted uranium, the recipes may be adapted to include other, more radioactive metals such as neptunium, whose effects are even more important to study, Nyman said.

Cesium - an element of particular concern in its radioactive form - proved to be, chemically, an especially favored template for the compounds to self-assemble.

The work was done as part of the Actinide Materials Department of Energy (DOE) Energy Frontiers Research Center (EFRC) led by professor Peter Burns at Notre Dame University. Using the new method, researchers at the University of California-Davis are studying how materials behave in water and in different thermal environments, while researchers at DOE's Savannah River Site study the analogous behavior of neptunium.

The research will be featured as the cover article of the May 3 online European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry, to be published in print May 13. It currently is highlighted in preview in the online ChemViews Magazine.