Apr 30 2014

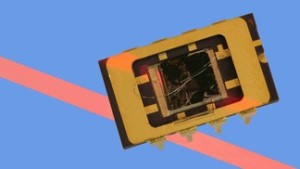

After using it to develop a computer chip, flash memory device and photographic sensor, EPFL scientists have once again tapped into the electronic potential of molybdenite (MoS2) by creating diodes that can emit light or absorb it to produce electricity.

© 2014 EPFL

© 2014 EPFL

Molybdenite has a few surprises still up its sleeve. After having used it to build an electronic chip, a flash memory device and a photographic sensor, EPFL professor Andras Kis and his team in the Laboratory of Nanoscale Electronics and Structures (LANES) is continuing his study of this promising semi-conductor. In research recently published in the journal ACS Nano, they have demonstrated the possibility of creating light-emitting diodes and solar cells.

The scientists built several prototypes of diodes – electronic components in which voltage flows in only one direction – made up of a layer of molybdenite superposed on a layer of silicon. At the interface, each electron emitted by the MoS2 combines with a “hole” – a space left vacant by an electron – in the silicon. The two elements lose their respective energies, which then transforms into photons. “This light production is caused by the specific properties of molybdenite,” explains Kis. “Other semi-conductors would tend to transform this energy into heat.”

Working in tandem

Even better, by inversing the device, electricity can be produced from light. The principle is the same: when a photon reaches the molybdenite, it ejects an electron, thus creating a “hole” and generating voltage. “The diode works like a solar cell,” says Kis. “Our tests showed an efficiency of more than 4%. Molybdenite and silicon are truly working in tandem here. The MoS2 is more efficient in the visible wavelengths of the spectrum, and silicon works more in the infrared range, thus the two working together cover the largest possible spectral range.”

The scientists want to study the possibility of building electroluminescent diodes and bulbs. This discovery could, above all, reduce the dissipation of energy in electronic devices such as microprocessors, by replacing copper wires used for transmitting data with light-emitters.

Author: Sarah Perrin

Source: Office de transfert de technologies