Aug 1 2014

Molybdenum disulfide is a compound often used in dry lubricants and in petroleum refining. Its semiconducting ability and similarity to the carbon-based graphene makes molybdenum disulfide of interest to scientists as a possible candidate for use in the manufacture of electronics, particularly photoelectronics.

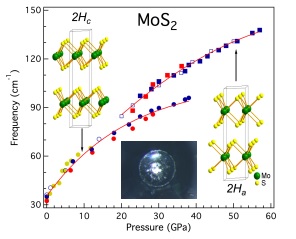

Intralayer vibrational coupling of molybdenum disulfide under hydrostatic pressure probed by Raman spectroscopy. Insets show the low- and high-pressure structures of molybdenum disulfide and a microphotograph of a diamond anvil cell cavity at 50 gigapascals, which shows the shining metallic molybdenum disulfide. Graphic courtesy of Haidong Zhang and Xiao-Jia Chen, both of Carnegie.

Intralayer vibrational coupling of molybdenum disulfide under hydrostatic pressure probed by Raman spectroscopy. Insets show the low- and high-pressure structures of molybdenum disulfide and a microphotograph of a diamond anvil cell cavity at 50 gigapascals, which shows the shining metallic molybdenum disulfide. Graphic courtesy of Haidong Zhang and Xiao-Jia Chen, both of Carnegie.

New work from a team including several Carnegie scientists reveals that molybdenum disulfide becomes metallic under intense pressure. It is published in Physical Review Letters.

Molybdenum disulfide crystalizes in a layered structure, with a sheet of molybdenum atoms sandwiched between sheets of sulfur atoms. But it was theorized that changing this structure, without inducing impurities into it, could turn it into a metal. That is, a structural transition might enable electrons to flow smoothly.

The team—including Carnegie's Alexander Goncharov, Haidong Zhang, Sergey Lobanov, and Xiao-Jia Chen—found a way to induce this metallic state by putting molybdenum disulfide under pressure in diamond anvil cells.

They found that molybdenum disulfide underwent structural changes as the pressure increased, and the compound began changing into a new phase. The team was able to determine that these changes were due to lateral shifting of the layers of molybdenum and sulfur.

This process started above 197,000 times normal atmospheric pressure (20 gigapascals), under which the new phase and interlayer stacking arrangement starts to appear and exist in conjunction with the old phase. The complete takeover of the new phase occurs at around 395,000 times normal atmospheric pressure (40 gigapascals), after which the compound became metallic.

They found that all of these changes were reversible when the pressure was decreased again.

"More work is needed to determine whether application of further pressure could yield superconductivity, a rare physical state in which mater is able to maintain a flow of electrons without any resistance at all," Goncharov said.

The rest of the team is comprised of lead author Zhen-Hua Chi of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, co-author Xiao-Miao Zhao of the Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research and South China University of Techonology, and co-authors Tomoko Kagayama and Masafumi Sakata of Osaka University.