Jiaxing Huang, associate professor of materials science and engineering at the McCormick School of Engineering at Northwestern University, has increased the efficiency of a proven thin-film fabrication technique called Langmuir-Blodgett assembly.

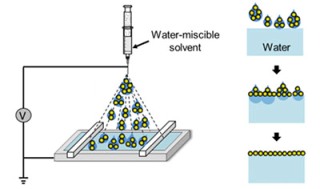

Using an elecrospray can spread a water-soluble solvent with nanoparticles onto water's surface without mixing.

Using an elecrospray can spread a water-soluble solvent with nanoparticles onto water's surface without mixing.

This new technique eliminates the use of toxic organic solvents by electrospraying materials on the surface of water.

This new approach also facilitates Langmuir-Blodgett assembly to be standardized easily, and scaled up safely. The Langmuir-Blodgett film deposition process was developed by Irving Langmuir and Katharine Blodgett in the 1930s, when they were working in the research laboratory of the General Electric Company.

Langmuir and Blodgett determined that one-molecule-thick films could be created when molecules are spread out with volatile organic solvents on water surface, and could be used as anti-reflective coatings for glass. Since then, the technique has been widely used to form molecule or nanoparticle monolayers, and to demonstrate a number of applications. However, there has been no significant change in the technique itself, nor in its procedure, since its introduction almost eight decades ago. Huang has now proposed a new approach.

“The use of organic spreading solvents causes a lot of problems, especially when people use this technique to assemble thin films of nanomaterials,” said Huang, associate professor of materials science and engineering at the McCormick School of Engineering. “Nanoparticles are usually hard to disperse and can even be damaged by the solvents, leading to poor quality of the final monolayer thin films.”

The study results have appeared in the Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS).

Langmuir-Blodgett assembly is advantageous in many ways over other thin-film fabrication methods. It tightly controls the packing density in the monolayer, enabling the formation of films with an exact number of layers. However, it is achievable only in the case of thorough dispersion of nanoparticles in both water surface and the spreading solvents.

“This is quite challenging,” Huang said. “It requires a very delicate balance of surface properties for nanoparticles to be well dispersed on water’s surface and in those water-hating solvents.

“There are also other problems,” said Hua-Li Nie, the first author of the paper and a former visiting scholar in Huang’s lab from Donghua University. “Nanoparticles made of polymers, organic compounds, or biological materials tend to be damaged in organic spreading solvents.”

“These volatile organic solvents also pose a safety hazard,” Huang added. “It becomes problematic when we think about manufacturing.”

All aforementioned problems can be avoided when nanoparticles are spread using a water-soluble, benign solvent like ethanol. However, the issue of particle sinking remains due to the water-solvent mixing.

“People have come up with many tricks to deal with this problem of sinking particles,” Huang said. “One way is to very gently disperse ethanol on water’s surface to avoid excessive mixing, but there is still a lot of wasted material.”

Using this strategy, Huang’s team performed Langmuir-Blodgett assembly of graphene oxide sheets. The study results appeared on the cover of JACS in 2009.

The new discovery by Huang involves the use of an aerosol spray to apply solvent without water-solvent mixing. Using the spray, the solvent containing the nanoparticles is broken down into millions of smaller droplets.

“If you reduce the size of the droplets to the micron range, they won’t ‘bombard’ the water’s surface,” Huang said. “Think about a humidifier: the water droplets float around because they are not very sensitive to gravity.”

Because the droplets are so small, the water can consume them as soon as they hit its surface. “Mixing with water is suppressed because there’s nothing left to mix,” Huang said.

The use of the electrospray helps achieve a good Langmuir-Blodgett assembly without the need for “skillful hands”. According to Huang, standardization and scaling up of this technique for industrial production is possible, owing to automation of electrosprays. This not only increases safety, but also minimizes time and money spent.

At present, toxic organic spreading solvents like chloroform are widely used for this purpose, necessitating maintaining the water trough in a controlled environment. This can be expensive to build and maintain in addition to safety concerns. Conversely, Huang’s new approach allows researchers to select any kind of benign liquid to be used as a solvent.

“We’ve broadened the landscape for Langmuir-Blodgett assembly,” Huang said. “A very simple idea — reducing the droplet’s size — has solved a longstanding problem for an old but popular technique.”