Polymer biocomposites are gaining research focus as sustainable, biodegradable alternatives to traditional plastic packaging.

Study: Artificial Ageing, Chemical Resistance, and Biodegradation of Biocomposites from Poly(Butylene Succinate) and Wheat Bran. Image Credit: HandmadePictures/Shutterstock.com

To investigate how raw wheat bran affects the accelerated aging and biodegradation of PBS biopolymer biocomposites when used as a filler material, a paper has been published in the journal Materials.

The Problem with Plastic Packaging

Whilst plastics have physical, mechanical, and chemical properties that make them useful for a variety of applications, their use comes with a huge cost. Traditional polymers are derived from hydrocarbons, which are a product of burning fossil fuels.

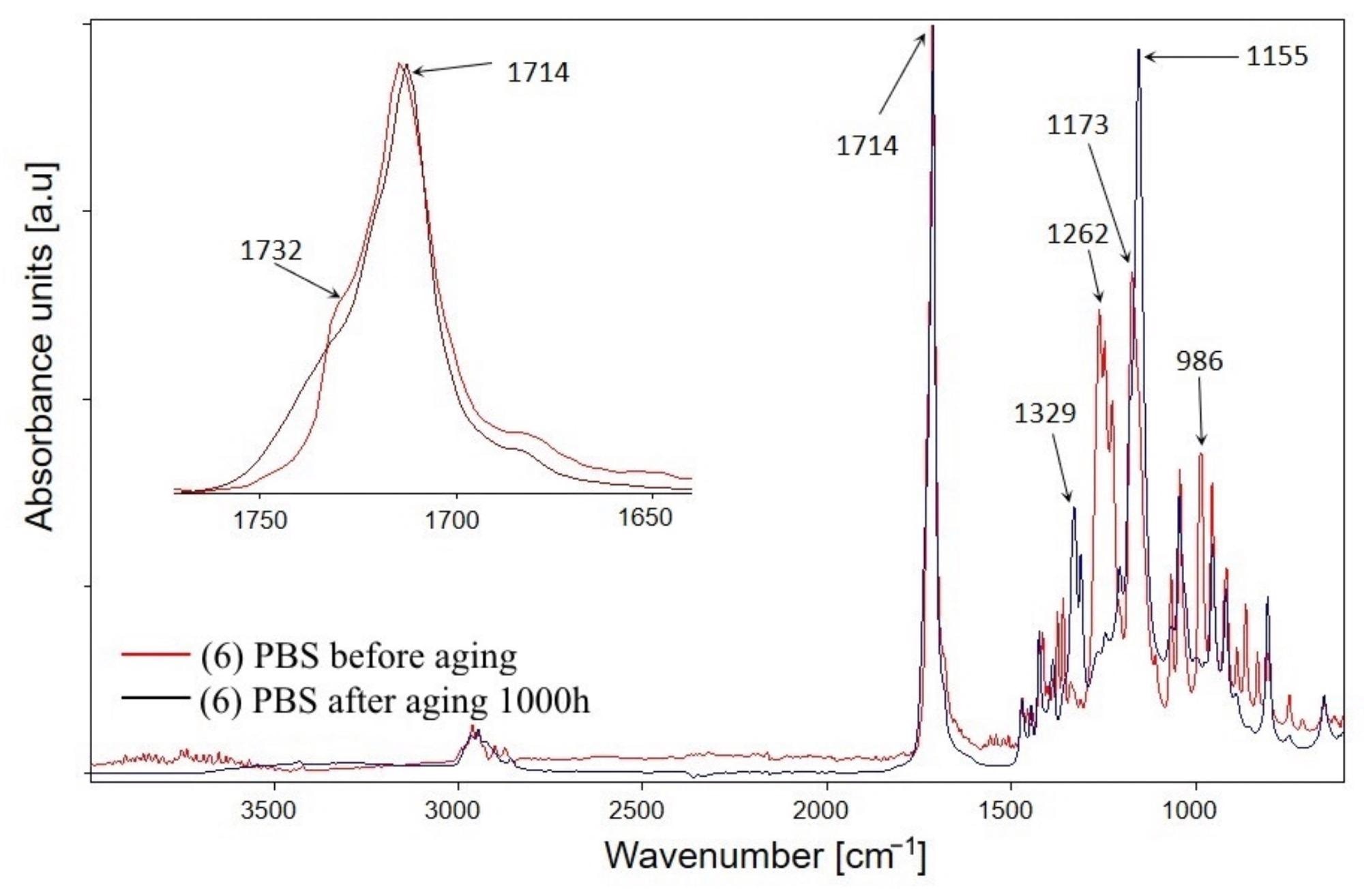

ATR-FTIR spectra of PBS acquired before and after aging test. Image Credit: Sasimovski, E et al., Materials

This not only causes harmful greenhouse gas emissions but also leads to growing amounts of waste. Plastic waste causes environmental damage to fragile ecosystems. Additionally, hydrocarbon-derived polymers take a long time to break down.

The problem with historical plastic waste already in the oceans and landfills is compounded by the growing demand for plastics from rapidly industrializing nations and the growing world population. Global production of plastics is predicted to double over the coming 15-20 years.

Using Biopolymers to Help Solve the Issue with Traditional Plastics

To address the challenges with plastic production and waste, biopolymers have increasingly been researched in recent decades to replace traditional hydrocarbon-derived plastics, especially for single-use plastics and packaging, two of the main sources of plastic waste globally. Biopolymers have the advantages of being sustainable and biodegradable and are derived from natural sources such as plants, microorganisms, and waste from the food and agriculture industries.

The term also applies to non-biodegradable polymers obtained from natural substrates. Biodegradable biopolymers are broken down by microorganisms into simpler molecules, removing them from the environment. The chemical structure of macromolecules mainly determines the kinetics of polymer degradation.

This translates into their resistance to oxidation from the action of enzymes, acids, and bases, the thermal resistance of polymers, and their chemical activity.

In addition to the action of microorganisms, biopolymers can be degraded by environmental influences such as temperature, mechanical degradation, photodegradation, oxidative degradation, corrosion, electromagnetic radiation, and hydrolytic degradation. Biopolymers differ in their response to degradation and the rate of degradation, which influences the choice of biopolymer for specific applications.

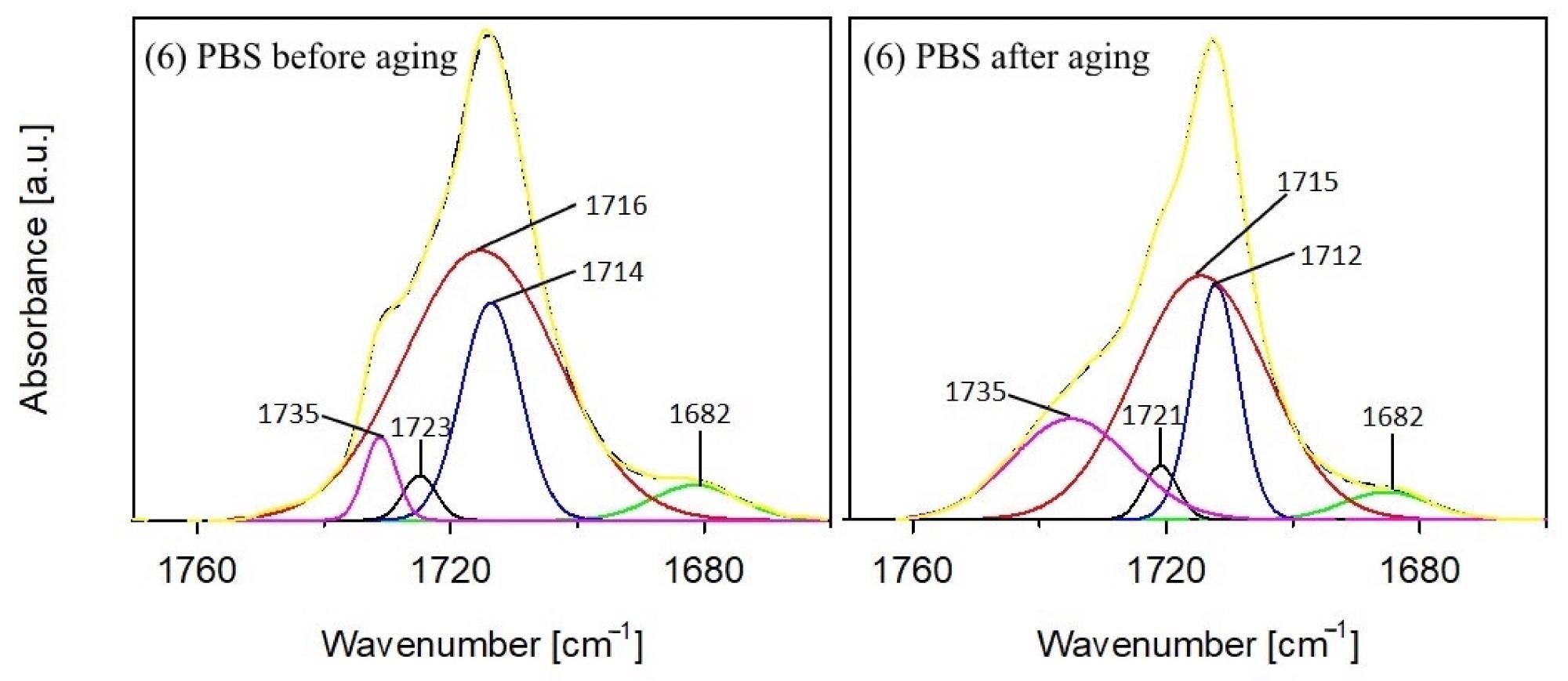

Deconvolution of the carbonyl stretching region of PBS before and after aging (dashed line: resolved peaks, solid line: recorded spectra). Image Credit: Sasimovski, E et al., Materials

Poly(butylene succinate)

Poly(butylene succinate) otherwise known as PBS, has gained prominence in biopolymer research in recent years due to its utility and attractive properties. Under normal conditions, PBS can be used for an extended period, and upon disposal (for example in composting) decomposes within a matter of months.

This biopolymer possesses superior mechanical properties, which are comparable to polyolefins, along with enhanced thermal resistance and good processability.

However, the material’s manufacturing process is complex and multi-step, and additionally, it is an expensive material to produce, and the industrial-scale manufacture of PBS still leaves an environmental footprint. Therefore, despite its rapid biodegradability, optimizing the manufacture of PBS to reduce its environmental impact, resource use, and improve its economic viability has gained research focus. Using lignocellulosic fibers as fillers have been explored in recent years.

Investigating the Effects of Raw Wheat Bran on PBS Biopolymers

Lignocellulosic fibers are organic in origin and are a byproduct of agricultural and food waste, of which one source is raw wheat bran. These fibers, when used as fillers in PBS matrixes to create composite materials, modify their mechanical, physical, processing, and thermal properties. They are hydrophilic and are less resistant to physical, chemical, and microbial factors which influence biodegradation.

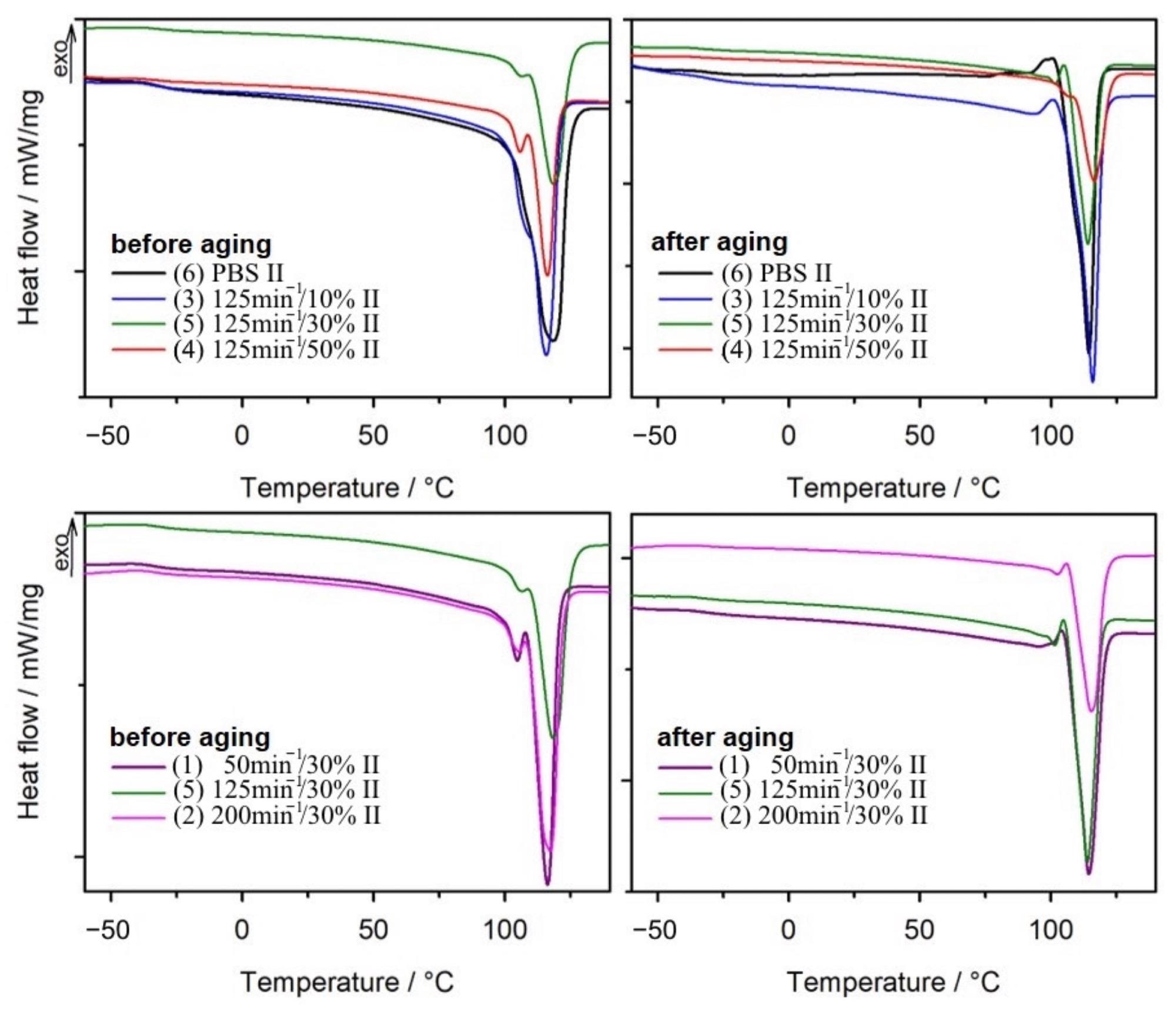

DSC thermograms of the second heating scans for PBS and composites obtained before and after aging. Image Credit: Sasimovski, E et al., Materials

The study published in Materials has investigated the influence of raw wheat bran on composite PBS biopolymer materials and how this affects the use of these materials as plastic alternatives, especially for packaging. The authors have stated that there is currently a lack of literature on the use of raw wheat bran as a composite filler for PBS biopolymers. They additionally state that the work will influence the future direction of research into these biocomposites. Currently, a patent is pending for the composite material.

The results of the research demonstrated that the resistance of the biocomposite to degradation factors is mainly dependent on the mass content of the filler material. Manufacturing conditions did not significantly affect the properties of composite pellets. From an economic standpoint, the need to produce composite materials efficiently was highlighted in the review.

The composite materials displayed enhanced disintegration in response to thermal, chemical, and microbial factors. Significant color changes were also observed.

The disintegration rate of biocomposites containing a 50% wheat bran composition was 68% after an incubation period of 70 days under test conditions, which was more rapid than unfilled PBS. The results of the study demonstrated that the proposed PBS/raw wheat bran biocomposite is compostable, which is highly advantageous from an environmental standpoint.

Further Reading

Sasimovski, E et al. (2021) Artificial Ageing, Chemical Resistance, and Biodegradation of Biocomposites from Poly(Butylene Succinate) and Wheat Bran [online] Materials 14(24) | mdpi.com. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/14/24/7580

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.