Dec 16 2010

Fortified with iron: It's not just for breakfast cereal anymore. University of Illinois researchers have demonstrated a simpler method of adding iron to tiny carbon spheres to create catalytic materials that have the potential to remove contaminants from gas or liquid.

Civil and environmental engineering professor Mark Rood, graduate student John Atkinson and their team described their technique in the journal Carbon.

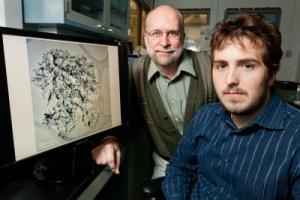

Civil and environmental engineering professor Mark Rood (left) and graduate student John Atkinson developed a novel method of producing porous carbon spheres with iron dispersed throughout them for catalytic and air quality applications.

Civil and environmental engineering professor Mark Rood (left) and graduate student John Atkinson developed a novel method of producing porous carbon spheres with iron dispersed throughout them for catalytic and air quality applications.

Carbon structures can be a support base for catalysts, such as iron and other metals. Iron is a readily available, low-cost catalyst with possible catalytic applications for fuel cells and environmental applications for adsorbing harmful chemicals, such as arsenic or carbon monoxide. Researchers produce a carbon matrix that has many pores or tunnels, like a sponge. The large surface area created by the pores provides sites to disperse tiny iron particles throughout the matrix.

A common source of carbon is coal. Typically, scientists modify coal-based materials into highly porous activated carbon and then add a catalyst. The multi-step process takes time and enormous amounts of energy. In addition, materials made with coal are plagued by ash, which can contain traces of other metals that interfere with the reactivity of the carbon-based catalyst.

The Illinois team's ash-free, inexpensive process takes its carbon from sugar rather than coal.

In one continuous process, it produces tiny, micrometer-sized spheres of porous, spongy carbon embedded with iron nanoparticles – all in the span of a few seconds.

"That's what really sets this apart from other techniques. Some people have carbonized and impregnated with iron, but they have no surface area. Other people have surface area but weren't able to load it with iron," Atkinson said. "Our technique provides both the carbon surface and the iron nanoparticles."

The researchers built upon a technique called ultrasonic spray pyrolysis (USP), developed in U. of I. chemistry professor Kenneth Suslick's lab in 2005. Suslick used a household humidifier to make fine mist from a carbon-rich solution, then directed the mist through an extremely hot furnace, which evaporated the water from each droplet and left tiny, highly porous carbon spheres.

Atkinson used USP to make his carbon spheres, but added an iron-containing salt to a carbon-rich sugar solution. When the mist is piped into the furnace, the heat stimulates a chemical reaction between the solution ingredients that creates carbon spheres with iron particles dispersed throughout.

"We were able to take advantage of Dr. Suslick's USP technique, and we are building upon it by simultaneously impregnating the porous carbons with metal nanoparticles," Atkinson said. "It's simple because it's continuous. We can isolate the carbon, add pores, and impregnate iron into the carbon spheres in a single step."

Another advantage of the USP technique is the ability to create materials to address particular needs. By fabricating the material from scratch, rather than trying to modify off-the-shelf products, scientists and engineers can develop materials for specific problem-solving scenarios.

"Right now, you take coal out of the ground and modify it. It's difficult to tailor it to solve a particular air quality problem," Rood said. "We can readily change this new material by how it's activated to tailor its surface area and the amount of impregnated iron. This method is simple, flexible and tailorable."

Next, the researchers will explore applications for the material. Rood and Atkinson have received two grants from the National Science Foundation to develop the carbon-iron spheres to remove nitric oxide, mercury, and dioxin from gas streams – bioaccumulating pollutants that have caused concern as emissions from combustion sources.

Currently, the three pollutants can be dealt with separately by carbon-based adsorbents and catalysts, but the Illinois team and collaborators in Taiwan hope to harness carbon's adsorption properties and iron's reactivity to remove all three pollutants from gas streams simultaneously.

"We're looking at taking advantage of their porosity and, ideally, their catalytic applications as well," Atkinson said. "Carbon is a very versatile material. What's in my mind is a multi-pollutant control where you can use the porosity and the catalyst to tackle two problems at once."