Aug 24 2016

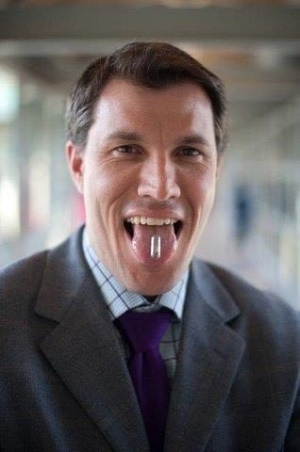

Christopher Bettinger, Ph.D., is developing an edible battery made with melanin and dissolvable materials. (Credit: Bettinger lab)

Christopher Bettinger, Ph.D., is developing an edible battery made with melanin and dissolvable materials. (Credit: Bettinger lab)

A team of researchers have reported their recent progress in the development of non-toxic, edible batteries. These batteries, which are made of melanin pigments found naturally in hair, eyes and skin, can be used to power ingestible devices employed for diagnosing and treating ailments.

The finding of the study was reported in the 52nd National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS) on 23rd August, 2016.

A battery-operated ingestible camera was developed two decades ago as a complementary tool for endoscopies. The camera can capture images of the digestive system that are beyond the access of the conventional endoscope. However, the camera is designed to be excreted.

The risk of the camera with a traditional battery getting stuck in the gastrointestinal tract is small when it is used once. However, if doctors wished to use it on a patient more than once, the chances of things going wrong increase.

For decades, people have been envisioning that one day, we would have edible electronic devices to diagnose or treat disease, but if you want to take a device every day, you have to think about toxicity issues. That’s when we have to think about biologically derived materials that could replace some of these things you might find in a RadioShack.

Christopher Bettinger, Ph.D.

A few implantable devices, such as pacemakers, and ingestible camera are powered by batteries that contain toxic components that are kept away from bodily contact. However, for drug-delivery devices that run on low power and are used repeatedly, degradable, non-toxic batteries are best suited.

The beauty is that by definition an ingestible, degradable device is in the body for no longer than 20 hours or so. Even if you have marginal performance, which we do, that’s all you need.

Christopher Bettinger, Ph.D.

Though longevity not a huge concern, toxicity is an issue. Bettinger’s team at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) chose to look at naturally occurring components, including melanins, in an attempt to reduce the potential damage of future ingestible devices.

Melanins present in human hair, eyes and skin absorb UV light to quench free radicals and to protect humans from damage. They also unbind and bind metallic ions. “We thought, this is basically a battery,” Bettinger says.

Adding to this concept, the scientists tested battery models that employ melanin pigments at the positive or negative ends; sodium titanium phosphate, manganese oxide and other electrode materials; and cations such as iron and copper used by the body for normal functioning.

We found basically that they work. The exact numbers depend on the configuration, but as an example, we can power a 5 milliWatt device for up to 18 hours using 600 milligrams of active melanin material as a cathode.

Hang-Ah Park, Ph.D., Post-Doctoral Researcher, CMU

Although a melanin battery does not have a capacity as high as a lithium-ion battery, it would have the ability to power an ingestible sensing or drug-delivery device.

For instance, Bettinger intends to use the battery developed by is team to deliver doses of a vaccine over many hours before degrading or for detecting changes in gut microbiome and reacting with a release of drugs.

In addition to melanin batteries, the team is simultaneously developing edible batteries using biomaterials such as pectin, which is a natural compound found in plants that are employed as a gelling agent in jellies and jams. The team intend to develop packaging materials that will ensure the safe delivery of the battery to the stomach.

The time for the incorporation of these batteries into biomedical devices is yet to be decided. Bettinger, however, has come up with another use for them.

The batteries are used to probe the chemistry and the structure of the melanin pigments themselves to gain a comprehensive understanding of their functions.

The research was financially supported by the Shurl and Kay Curci Foundation and the National Science Foundation.