May 2 2017

There are headaches, and then there is post–dural puncture headache (PDPH)—a severe and debilitating side effect of spinal and epidural anesthesia that may last three weeks or more without treatment.

Credit: http://www.anesthesiologynews.com/

Credit: http://www.anesthesiologynews.com/

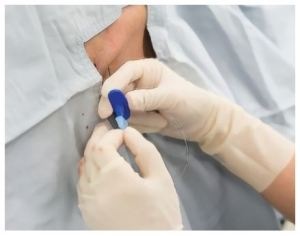

Epidural steroid injections are regarded as a safe and effective treatment for PDPH, but minor complications such as wrong-site tissue injection and dural puncture can occur (Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2014;58:858-866). And yet, epidurals have been administered the same way for nearly 80 years.

“It’s a relatively crude technique,” said Thomas Anthony Anderson, MD, PhD, an anesthesiology faculty member at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School, in Boston. “That’s why we’re developing technologies to improve this procedure without significantly altering workflow.”

Real-time needle-tip spectroscopy, which identifies tissue type, could be a potential alternative to epidural steroid injections, according to new research by Dr. Anderson that was presented at the 2017 annual meeting of the Society for Technology in Anesthesia (abstract 3). The spectroscopic technique could aid epidural needle placement, improve pain control and possibly patient outcomes, and potentially reduce hospital costs.

“Neuraxial anesthesia and epidural steroid injection techniques require precise anatomical targeting to ensure successful and safe analgesia. The loss-of-resistance technique is the most common method of locating the epidural space but suffers from a lack of specificity,” Dr. Anderson said. “These are generally low-risk procedures, but when mistakes occur, they can be catastrophic, leading to stroke or spinal cord injury.”

A review of the medical literature showed that up to 6% of patients who undergo epidural anesthesia suffer from PDPH (Int J Obstet Anesth 1998;7:220-225). Although more conservative estimates place that percentage in the range of 1% to 2%, 10% of epidurals may fail from a false loss of resistance, he observed. Thus, of the 5 million patients in the United States who receive an epidural for labor and delivery or postoperative pain control each year, approximately 50,000 to 100,000 of them will have PDPH and require some form of treatment, while 500,000 epidurals may fail to work.

Study Design and Preliminary Results

Dr. Anderson and his colleagues previously showed that Raman spectroscopy can differentiate tissue from the skin to the spinal cord with a high degree of accuracy and precision in an ex vivo swine model (Anesthesiology 2016;125:793-804). For this study, they tested the ability of a 500-mcm outer diameter Raman spectroscopic probe to identify the same tissues in a live animal model.

“A miniaturized Raman spectroscopy probe, compatible with an epidural needle, may prove useful during needle placement by providing evidence of its anatomical localization,” Dr. Anderson said.

The probe was compatible with a 17-gauge Tuohy epidural needle and low-cost Raman spectroscopy system, the authors noted. The probe was inserted in midline and paramedian trajectories, and advanced at 2-mm increments from the skin to the spinal cord. Data were recorded during multiple midline and lateral insertion points while simultaneous x-ray imaging captured needle tip position relative to the spinal column. Finally, spinal tissue was removed and tissue along each needle trajectory was dissected. The dissected tissue underwent hematoxylin and eosin staining and pathologist identification.

“It’s still early in the testing, but preliminary analysis of Raman spectra acquired during live animal insertion of the probe suggests unique spectra for each tissue,” Dr. Anderson said. “The probe-in-needle appears to identify all tissues from skin to spinal cord necessary for epidural placement, and will allow us to do simultaneous loss of resistance. … It looks very promising.”

Dr. Anderson and his colleagues plan to begin human cadaver studies followed by a healthy volunteer human trial after completing the final analysis.

Additional Indications

The researchers envision broader applicability for the device. They have started expanding the technology to other procedures involving a blind or semi-blind approach, including laparoscopic surgery, joint injections and various tissue biopsies. They noted that even neurosurgeons at Massachusetts General Hospital have expressed interest in the technology.

“The first intracranial tumor biopsies are negative about half the time, and even the second biopsy can fail,” Dr. Anderson said. “No one has built a probe that will fit through the needle and differentiate between normal brain tissue and brain tumor. There is a chance that Raman spectroscopy could improve the accuracy of this procedure.”

The researchers also are working with gastroenterologists and pulmonologists to overcome the limitations of ultrasound and fluoroscopy to biopsy a variety of tissues. Ultrasound and fluoroscopy can localize epidural needles relative to bone, but they lack resolution and are unable to identify tissues at the needle tip, according to Dr. Anderson.

“Ultrasound and x-rays are wonderful technologies, but each has limitations, just like Raman spectroscopy,” he said. “We’re trying to approach these problems from a different mindset, and hopefully, we’ll be able to develop a device that won’t cost an arm and a leg but will make our patients safer.”

Kirk Shelley, MD, PhD, professor of anesthesiology and chief of ambulatory anesthesia at Yale School of Medicine, in New Haven, Conn., designated Dr. Anderson’s study as one of the highlights of the meeting.

“Use of Raman spectroscopy to improve needle placement is quite innovative,” Dr. Shelley said, “and there are potentially many exciting applications for this technology.”

—Chase Doyle