Nov 5 2018

Numerous products such as cosmetics, detergents, and clothes are made using petroleum, making such common items anything but environmental-friendly. It is currently possible to create the bio-based and CO2-neutral basic chemicals for such products with the help of fungi. Fraunhofer research teams are formulating fermentation methods and manufacturing processes to make them on an industrial scale.

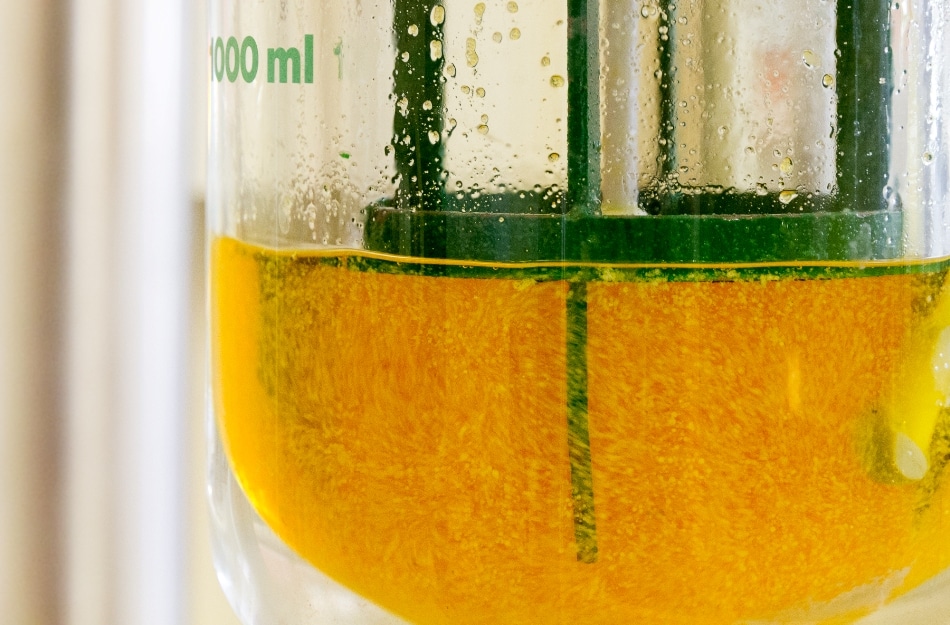

Laboratory-scale bioreactor for optimizing fermentation conditions. (© Fraunhofer IGB)

Laboratory-scale bioreactor for optimizing fermentation conditions. (© Fraunhofer IGB)

If a layer of blue-green mold is seen covering fruit, bread, or something else from the pantry, one will quite rightly end up disposing it into the trashcan—fungi are after all detrimental to one’s health. Scientists at the Fraunhofer Institute for Interfacial Engineering and Biotechnology IGB in Stuttgart, however, are particularly interested in molds, especially the genus Aspergillus. They are also keen about smut fungi and yeast. Why?

Fungi have long been indispensable for antibiotic production or in the food industry. The fungi we employ help us to synthesize a variety of chemicals in a CO2-neutral way. They’re the basis for detergents, emulsifiers, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and plastics.

Steffen Rupp, Professor, Head of the Department of Molecular Biotechnology, Deputy Director, Fraunhofer IGB.

Unlike petroleum, extracting chemicals from renewable raw materials does not discharge CO2 into the atmosphere. Moreover, using fungi as production organisms has another huge advantage: The pool of probable production organisms is almost unlimited, as is the range of renewable raw materials they can transform. As the fungi use a multitude of different metabolic pathways, they create an amazing range of products, which can be used in a wide variety of applications.

From malic acid to bio-surfactants and polyesters

Scientists at Fraunhofer IGB create a wide range of chemicals using fungi. One instance is malic acid. There is a constantly growing market for the substance, which gives products such as juices and jams a sour taste and enhances the shelf life of baked goods. It can also be employed as a building block for bio-based polyesters. Plus, in a process like brewing beer, it can be created using molds. In beer brewing, the yeast ferments the malt sugar of barley, while in malic acid production Aspergillus fungi convert vegetable oils or sugar.

This can be achieved by “feeding”, for example, a wood-based sugar solution to the fungi to make them produce malic acid. Fermentation like this suits a laboratory scale. The IGB scientists are presently exploring ways to scale up the process for commercialization, specifically, by enhancing the fermentation yield.

Using a related process, they can also form surface-active agents that can be used to create pharmaceutics, emulsifiers, detergents, active ingredients for cosmetics, and pesticides. That’s where the smut fungi enter into the picture. They are parasites that invade plants, making them appear like they have been burned—hence their Germanic name, Brandpilze [burnt fungi].

The process is another one we’re actively developing for industrial production. Our principal goal is to optimize the composition of the biosurfactants we produce to suit various applications in the field of detergents and emulsifiers.

Dr. Susanne Zibek, Head of the Industrial Biotechnology Group.

Yeasts are also fascinating producers. Besides brewing beer, as mentioned beforehand, some yeast can also be used to create molecules that are vital for synthesizing new plastics, such as long-chain dicarboxylic acids. The scientists at Fraunhofer IGB have done well in working out a method to create long-chain dicarboxylic acids from a strain of Candida.

Scaling up: the Fraunhofer pilot plant and biorefinery

If the bio-based chemicals are to be employed in industrial applications—whether as food components such as malic acid, as surfactants, or as molecular building blocks for plastics—they will have to be synthesized on a large scale. This is a tough challenge: the global production of surfactants, for example, is 18 million metric tons per year. “Scaling-up the processes from kilograms to tons involves a great deal of engineering and computing,” explains Fraunhofer researcher Zibek. There are still queries that have to be answered: How to perfect the composition of the fermentation media? What is the ideal way to feed the fungi? Scientists are primarily addressing such questions on a small scale.

Once this difficulty has been sorted, the scientists at the Fraunhofer Center for Chemical-Biotechnological Processes CBP will then need to define the processes for large-scale production. They work a pilot plant in which the fermentation processes can be expanded up to a maximum of ten cubic meters. Such a massive volume requires a huge amount of raw materials; after all, the fungi need feeding. The favored source for the researchers is wood sugar, in other words, sugar solutions that contain xylose as well as glucose. These can be gotten directly in the Fraunhofer CBP ligno-cellulose biorefinery and blended into the culture medium.

Consecutively, this provides the molds and other fungal organisms with ideal growth conditions using renewable raw materials, allowing them to yield numerous chemicals.