South Dakota State University’s assistant professor of dairy and food science, Srinivas Janaswamy, is aiming to make a transparent, biodegradable film from crop residue and native grasses that would benefit the farmers and also the environment.

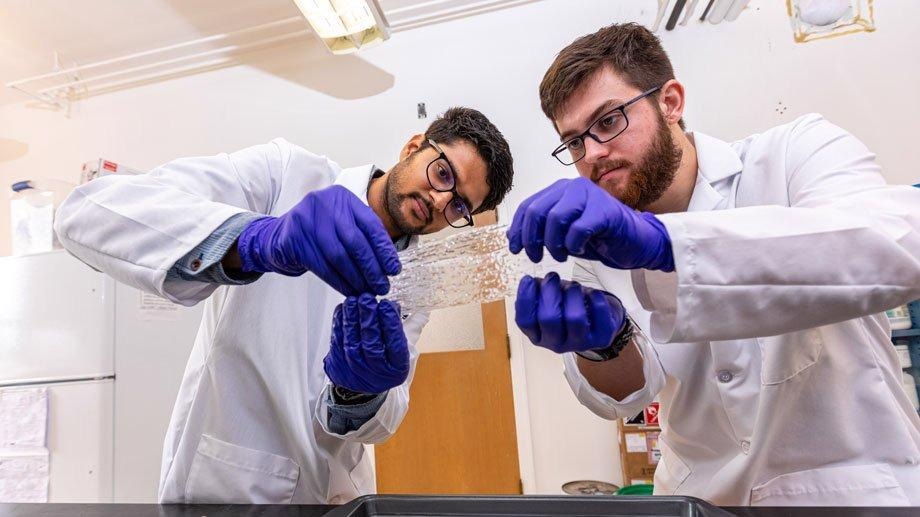

Master’s student Sajal Bhattarai, left, and undergraduate Jake Larsen examine the smooth, clear film they have made from the cellulose gel. The next step will be to test its strength and biodegradability. The goal of the USDA project is to extract cellulose fractions from renewable agricultural residues to make strong, biodegradable films. Image Credit: South Dakota State University.

Master’s student Sajal Bhattarai, left, and undergraduate Jake Larsen examine the smooth, clear film they have made from the cellulose gel. The next step will be to test its strength and biodegradability. The goal of the USDA project is to extract cellulose fractions from renewable agricultural residues to make strong, biodegradable films. Image Credit: South Dakota State University.

Srinivas Janaswamy is pursuing the current research through a three-year U.S. Department of Agriculture grant of $481,618.

We are extracting cellulose fraction from renewable agricultural residues and then solubilizing it to make strong biodegradable films.

Srinivas Janaswamy, Assistant Professor, Dairy and Food Science, South Dakota State University

Janaswamy is also a South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station researcher. Employing the nation’s ample supply of agricultural biomass to produce biodegradable products that replace petroleum-based plastics will minimize the effect of the packaging materials on the environment along with generating additional income for farmers.

Janaswamy is involved in developing techniques to extract cellulose fraction from wheat and oat straw, corn stover and soybean biomass, and switchgrass and prairie cordgrass through the National Institute of Food and Agriculture project.

Janaswamy’s team includes lecturer Michael Twedt of SDSU’s Department of Mechanical Engineering and senior research scientist Madhav Yadav of the USDA Agricultural Research Center in Wyndmoor, Pennsylvania. Data created from a North Central Regional Sun Grant Center project assisted Janaswamy in securing the USDA funding.

Farmers usually bundle up corn stalks and leaves for livestock feed and bedding and leave the rest in the field to enhance soil health. According to Janaswamy, “Both are important,” however, he notices the probability of gaining extra profit by using a fraction of the corn residue for biodegradable plastics.

Suppose a ton of corn stover costs $83, on the basis of its value as livestock feed, and using a conservative yield estimate of 1 ton of corn stover per acre, a farmer can generate roughly $33,000 of additional revenue by selling 40% of the corn stover from a 1,000-acre cornfield, all the while reserving 30% for soil health and 30% for livestock.

“Instead of putting all eggs in one basket, distributing them could be more advantageous, not only to address plastic pollution issues but also to gain extra dollars,” Janaswamy said.

Improving process

The plant biomass is composed of three components — cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. In the earlier Sun Grant research, corn stover cellulose extract produced a biodegradable film that was gray due to the presence of lignin.

The current project started in November and Janaswamy announced, “We have been able to remove the lignin and get a pure, white cellulose material from corn stover.” Doctoral student Shafaet Ahmed and master’s students Mominul Hoque and Sajal Bhattarai are also involved in this project.

Additionally, SDSU agronomy major Jake Larsen of Sioux Falls contributed to the project this summer through the Research Experience for Undergraduates.

“Dr. ‘Jana’ provided me with a pulpy cellulose mixture (made from corn stover) and a process, which he anticipated would make a substance close to cardboard,” Larsen commented. The process, however, produced white cellulose granules from which the scientists created a clear film.

The process turned out better than I expected. This is a patentable process.

Srinivas Janaswamy, Assistant Professor, Dairy and Food Science, South Dakota State University

Addressing different feedstock

The researchers are now implementing the extraction process to other agricultural by-products and native grasses. As the feedstock composition is different, the cellulose fraction process is adjusted to suit each type of feedstock.

“There is not just one solution — they will all be different,” added Janaswamy. The properties of the film would also vary based on feedstock type.

Once we extract cellulose from each feedstock type, we will compare the properties of the films.

Srinivas Janaswamy, Assistant Professor, Dairy and Food Science, South Dakota State University

The films should contain three attributes. They should be strong enough to resist tearing, transparent so that manufacturers can impart any color, and biodegradable. “When you put them into the soil, they should disappear over time – 30 to 60 days is the goal,” Janaswamy adds.

After accomplishing these goals, the researchers intend to go back to the extraction steps and make sure the whole process is economical.