May 13 2013

To make useful things, humans remove the bits that aren’t part of the thing we want. We've learned how to then make giant factory machines that assemble the different parts into a more complex whole. It’s called “reductive” manufacturing — with some assembly required — and has dominated our lives for thousands of years.

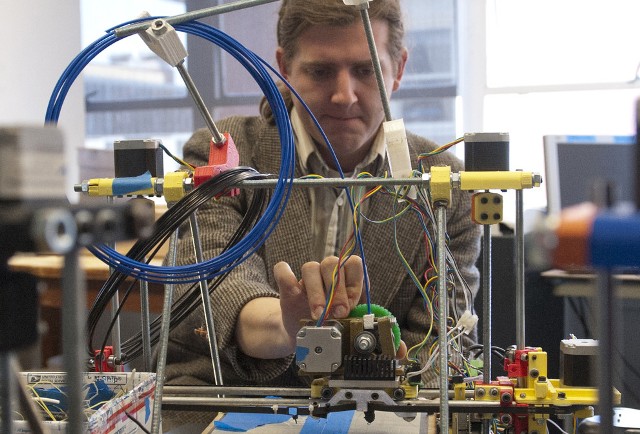

David Saint John, an instructor in Penn State's College of Engineering, working with a 3-D printer constructed by engineering students. The printers can create 3-D solid objects from digital models. Image: Patrick Mansell

David Saint John, an instructor in Penn State's College of Engineering, working with a 3-D printer constructed by engineering students. The printers can create 3-D solid objects from digital models. Image: Patrick Mansell

From chipping flint arrowheads millennia ago, to carving wooden tools, to assembling chairs or tables from Ikea, to Michelangelo saying his job was to whack away waste marble, from a shapeless block, anything that didn’t look like an angel; to drilling and molding and stamping and extruding and assembling parts for rocket engines and patio furniture and giant oil tankers — we make things, by the billions, mostly through variations of reductive manufacturing processes. And, we’ve gotten very, very good at it.

But that approach is changing, and with it our future.

“3-D printing” — the colloquial name for “additive manufacturing” — is a technology that theoretically enables us to make almost anything by building it up rather than cutting something away.

Food. Guns. Toothbrushes. Shoes. Art. Clothing. Jewelry. Building materials. Electronic devices. Car dashboards. Moon habitats. Office buildings. Transplantable human organs and living tissue for medical research.

Penn State faculty and a growing group of students are fully engaged in research and practical experiments in this new world, and these programs are gaining attention and enrollments.

3-D printing as a reality has been around for a decade or more. Boosted by the rocket fuel of the Internet and a culture of collaboration and Open Source communities, and breathtaking advances in software and computing power, it is starting to hit the mainstream, earning mentions in presidential speeches and cover stories in magazines. Do a Google search for “3-D printing” and be prepared to skim through hundreds of links.

With this technique, objects are built up in layers — sometimes only microns thick — in three dimensions. The technology has been around for a decade at least, and has been used mostly to make models in architecture, car designs and other fields. In the past couple of years, however, it is gaining new interest and sparking innovation through advances in computer aided design (CAD) software and the Internet as it links researchers, tinkerers and entrepreneurs together.

It may reduce fossil fuel use by requiring less raw material and shorter supply lines, and can create completely new designed objects that cannot be made with old methods. The ripples of change on a global scale will ride faster development of new designs, less dependence on fossil fuels for transportation and faster retooling or increased customization.