Aug 22 2016

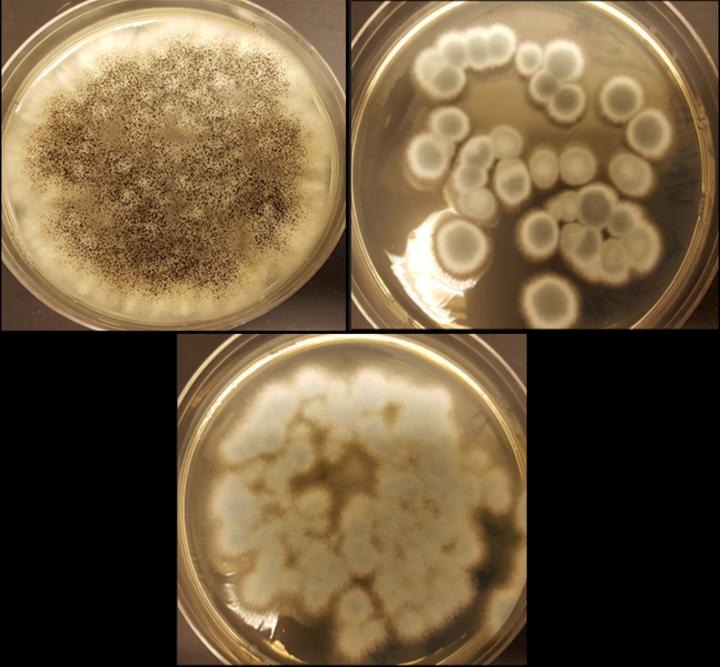

The fungi Aspergillus niger (top left), Penicillium simplicissimum (top right) and Penicillium chrysogenum (bottom) can recycle cobalt and lithium from rechargeable batteries. Credit: Aldo Lobos

The fungi Aspergillus niger (top left), Penicillium simplicissimum (top right) and Penicillium chrysogenum (bottom) can recycle cobalt and lithium from rechargeable batteries. Credit: Aldo Lobos

Rechargeable batteries in tablets, cars and smartphones do not last forever, even though they can be repeatedly charged. Very often old batteries end up in incinerators or landfills, which could potentially harm the environment, and valuable materials continue to remain locked inside.

Currently, a team of researchers are turning towards naturally occurring fungi in order to develop an environmentally friendly recycling process to extract lithium and cobalt from tons of waste batteries.

On 21 Aug, 2016, the team presented their work at the 252nd National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS is considered to be the largest scientific society in the world, and the meeting features more than 9,000 presentations based on a variety of science topics.

The idea first came from a student who had experience extracting some metals from waste slag left over from smelting operations. We were watching the huge growth in smartphones and all the other products with rechargeable batteries, so we shifted our focus. The demand for lithium is rising rapidly, and it is not sustainable to keep mining new lithium resources.

Jeffrey A. Cunningham, Ph.D.

Even though it is a global issue, the U.S. is considered to be the largest generator of electronic waste. It is still not clear how many electronic products are recycled.

Most likely, many of the products are sent to a landfill in order to slowly break down in the environment or they are burnt in an incinerator, resulting in the production of potentially toxic air emissions.

A few methods require harsh chemicals and high temperatures, and they exist to split cobalt, lithium and other metals. The team headed by Cunningham is currently developing an environmentally technique to do this with organisms existing in nature, for instance fungi, and placing them in an environment where they can carry out their task. "Fungi are a very cheap source of labor," he points out.

Cunningham and Valerie Harwood, Ph.D., both at the University of South Florida, are pursuing this process by using three strains of fungi, Penicillium chrysogenum, Penicillium simplicissimum and Aspergillus niger.

We selected these strains of fungi because they have been observed to be effective at extracting metals from other types of waste products. We reasoned that the extraction mechanisms should be similar, and, if they are, these fungi could probably work to extract lithium and cobalt from spent batteries.

Jeffrey A. Cunningham, Ph.D.

First, the team dismantled the batteries and pulverized the cathodes. Next, the remaining pulp was exposed to the fungus.

"Fungi naturally generate organic acids, and the acids work to leach out the metals," Cunningham explains. "Through the interaction of the fungus, acid and pulverized cathode, we can extract the valuable cobalt and lithium. We are aiming to recover nearly all of the original material."

The results obtained so far highlight that the use of two organic acids, citric acid and oxalic acid, generated by the fungi helped extract up to 48% of the cobalt and 85% of the lithium from the cathodes of spent batteries.

However, gluconic acid failed to be effective for extracting either metal.

Cunningham highlights that after fungal exposure the lithium and cobalt continue to remain in a liquid acidic medium. He now aims to remove the two elements from that liquid.

We have ideas about how to remove cobalt and lithium from the acid, but at this point, they remain ideas. However, figuring out the initial extraction with fungi was a big step forward.

Jeffrey A. Cunningham, Ph.D.

While other researchers are similarly trying to remove metals from electronic scrap, Cunningham assumes that his team is the only one analyzing fungal bioleaching for spent rechargeable batteries.

Currently, Cunningham, Harwood and graduate student Aldo Lobos are exploring a variety of fungal strains, the acids produced by them and the efficiency of the acid to extract metals in varied environments.